For the sake of Earth and humanity, it’s time for private enterprise and governments to co-invest to expand human activity in low Earth orbit.

To some, that will appear to be a preposterous statement. How can human space flight help hard problems on Earth? What justifies public-private investment?

For more than 60 years, discretionary tax dollars have underwritten both the exploration of space and the development of technologies needed to travel and work there.

Over that same time, our world’s population has more than doubled. The relentlessly increasing demand for energy, materials, land, and waste disposal has severely damaged the only biosphere we have. We know that the unique perspective from space changes how people feel about challenges and conflicts on Earth. And we know that space holds infinite energy, materials, and room to grow.

Exploring is only one of four major pursuits to undertake in space. We can also experience space for ourselves as we do by vacationing in exotic locales on Earth. We can exploit the locations, conditions, and resources space has to offer. And ultimately, we can expand civilization into space where we find unlimited resources. While these four possible futures are related, each is animated by unique goals, favors certain destinations, requires specialized technologies, and yields distinct benefits.

Human expansion into the solar system will require almost inconceivable investments, sustained over centuries. Only two of the futures move down this path because their economic engines are powered by mass markets: people who want to experience space travel, and commercial enterprises that seek to exploit what space has to offer. Together, these two markets will control the growth rate of our future in space, so they should be the focus of governments interested in promoting economic growth. Fortunately, both markets can take off in low Earth orbit.

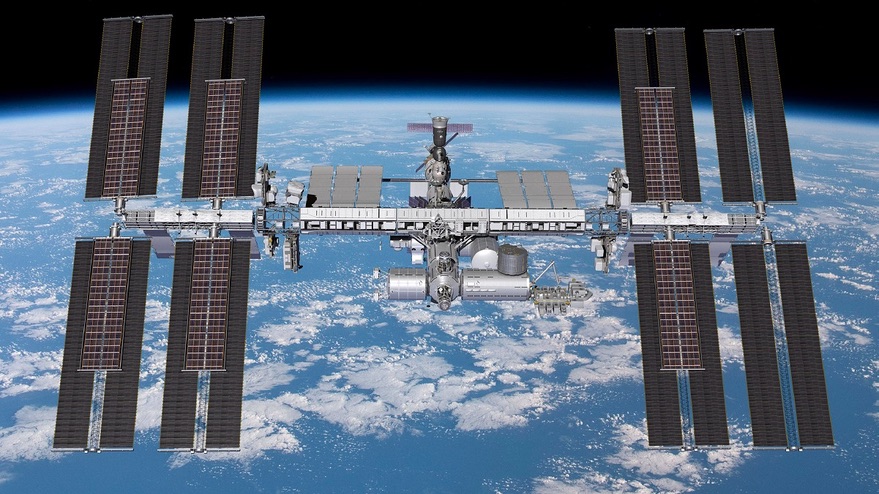

The International Space Station, multiple Russian space stations before it, Skylab, and now Chinese space stations as well, have all established real markets for permanent national presence and scientific research in orbit. Exploring frontiers is how governments create options. But realizing those options takes commercial enterprise building in the wake of exploration, enabled by public infrastructure and conducive regulations. Now, with the right conditions, commercial interests are poised to build on the government foundation in low Earth orbit by investing in three rich orbital markets.

First, sovereign nations around the globe – those already active in space, but also newcomers that have never had easy access to space – will pursue an “orbital address.” Nations will aim to position themselves on this visible frontier of technology and commerce. And the fundamental research sponsored by NASA and other agencies will continue.

Second, a wide range of commercial interests will experiment in and seek profit from the unique orbital environment: hard vacuum, containerless processing, no convection, high energies, and proximity to home. The latent opportunities are endless for technology development, manufacturing at scale, Earth imaging, data processing, advertising, media, sports, and gaming.

Third, private space travel is now real. Larger numbers of people will experience space flight’s novel sensations: launch acceleration, re-entry deceleration, free-fall for days or weeks, and the dominating, ever-changing view of Earth. Imagine making commonplace the experience of sixteen sunrises and sunsets per day, while also overflying ninety percent of humanity. Adventurers first, and then orbital residents will visit and occupy space destinations.

Why hasn’t this all happened already?

First, we need a method to fly payloads and people routinely, safely, and more affordably. Soon, there will be two privately owned, reusable heavy lift launch systems and four reusable space vehicles. Second, we need an accessible orbital destination where entrepreneurs can test their designs and seek their fortunes – a place that promotes competition. Soon, there will be a commercially developed, owned, and operated space station designed with these markets foremost in mind. Third, we need established space research customers to sign long-term use agreements as anchor tenants to give investors confidence. NASA’s Commercial LEO Destinations program must be funded to develop accommodations for its special needs and structured to make long-term deals. Fourth, we need private capital to make sustained investments with the patience to await the delayed returns from emergent markets.

As a founder of the field of space architecture, I’ve worked for a half century to normalize space flight. Space is the ultimate environment in which we can grow and thrive. It is also a domain that reveals – viscerally – the limits and interconnectedness of our existence on Earth.

Humanity needs a space destination close to home. A place in low Earth orbit where customers can experience space simply by buying a ticket, with all essential services and concierge amenities expertly and safely provided. A place where they can learn to feel at home in this hostile environment, experimenting and inventing new products that markets have yet to imagine. A place where people from around the planet can gaze in awe together through expansive windows across the vacuum of space. A place with an incomparable view of our fragile existence on our only home – our blue origin.

An orbital address will be where it all starts.

Brent Sherwood is a space architect with 33 years of experience in the space industry. He is Senior Vice President of Advanced Development Programs for Blue Origin, which develops systems for space transportation, space mobility, space destinations, and lunar permanence. Blue Origin’s mission is to develop infrastructure for millions of people to live and work in space to benefit Earth.