Electric Lit is 12 years old! Help support the next dozen years by helping us raise $12,000 for 12 years, and get exclusive merch!

It’s easy to make fun of the folkniks—those mostly college kids in the late 50s and early 60s who suddenly turned to sea shanties, work songs, and banjos for their musical pleasure. At least, on screen they have served as reliable joke fodder. From the soporific earnestness of the cast in A Mighty Wind, to the pathetic bumbling of Inside Llewyn Davis, to naïve Greenwich Village scenesters in Mad Men, folk fans and their comrades have recurred as fools in modern day media portrayals, inflexibly committed to impossible ideals of authenticity.

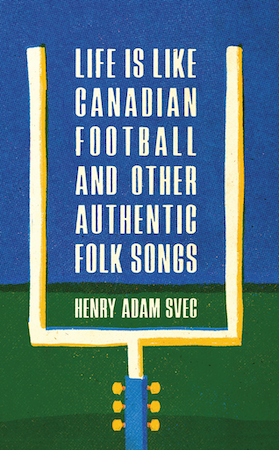

There are a few so-called folkniks in my new novel, Life Is Like Canadian Football and Other Authentic Folk Songs, and I’ve written more than a few jokes at their expense. It is hard to resist. However, I also wanted to grapple with some of the deeper complexities of the North American folk revival, still ongoing, and the long process by which grassroots musical traditions have been variously preserved, deployed, and/or reimagined. What if authenticity was not to be found out in a field or seaside village, but rather to be built in and through communication technologies? What if Woody Guthrie’s fascist-killing guitar could be repurposed or modulated by singers and citizens alike?

Or, what if a grad student could find, in the basement of Library and Archives Canada, tapes of the folk songs of the Canadian Football League, documented by a late communist song collector from the 60s named Staunton R. Livingston, who had developed a revolutionary philosophy of phonography? What if that grad student could mobilize this knowledge by building an artificially intelligent database of folk songs? What personal, professional, and political destinies would then unfold?

I read a lot of scholarly (and pseudo-scholarly) writing about North American folk music as I researched. I also began to realize that there are already a handful of interesting novels out there connected, with varying degrees of directness, to folk revivalism. Here are some of the ones I like best.

Dissident Gardens by Jonathan Lethem

Three generations of activists in New York City reckon with the influence of Rose, their difficult matriarch. Rose’s daughter Miriam and her folk-singing husband Thomas seek meaningful ways to contribute to history; decades later their Quaker son connects with his father’s legacy; and a stepson, the scholar Cicero, finds himself immersed in the milieu of academic critical theory. With characteristic verve and style, Lethem weaves relationships between individuals and collectivities, history and action, from the Popular Front to Occupy Wall Street.

The Favorite Game by Leonard Cohen

Leonard Cohen had already published four books by the time his first album was released in 1967. In The Favorite Game, we follow Lawrence Breavman—perhaps the horniest character ever in Canadian fiction—skulking and longing across the streets of Montreal. As Breavman follows his instincts by becoming a poet, he also moves alongside, and then in opposition to, the family, friends, lovers, and city by which he has come to find himself entangled. In his debut novel, Cohen gives us a sizzling, ironic, proto-hippy love letter to desire and its immortalization as art.

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston was less a musician per se than a folklore and music collector, and author. However, she incorporated music into some of her literary projects in the 1930s. She displays a folklorist’s attention to speech and myth in the writing of her most celebrated book, Their Eyes Were Watching God. The novel centers on a young Black woman in Florida who seeks to find her way in love, through a sequence of uniquely challenging partnerships, on her own terms. The evocative imagery of the narrator, and the no less memorable rhetorical power of the characters, make Hurston’s 1937 novel an entrancing work to this day.

The Diviners by Margaret Laurence

Part of a cycle of novels involving Margaret Laurence’s fictional town of Manawaka, The Diviners sees Morag Gunn reaching middle age, floundering in her work as a writer of fiction. The text dovetails between present and past: Morag flees her isolating hometown to pursue a life of the mind, then becomes trapped by marriage with a professor. She connects sporadically with the wandering Jules, a Métis country musician, as she raises their child—mostly alone. Ultimately, it is through Jules’ rarely sung original ballads that both Morag and her daughter find the courage to carry on as storytellers.

Bound for Glory by Woody Guthrie

Long before Jack Kerouac and his speed-addled buddies hit the road, Woody Guthrie had already been there and written a book about it. Bound for Glory is often designated as an autobiography, and it does follow the life of the hugely influential artist from his early years in Oklahoma, marred by a series of family tragedies, to his arrival in New York City as a protest singer. And yet, boasting several memorable sequences—including his days on Los Angeles’ Skid Row, and a climactic, confrontational performance at the Rainbow Room—Guthrie deploys a novelist’s sense of setting and character. I think of it as Huckleberry Finn meets Steinbeck.

Festival Man by Geoff Berner

Geoff Berner’s biting klezmer-punk folk songs are often delivered from the lofty vantage point of sage or seer. But in his novel Festival Man, he has some fun taking on the voice of a less trustworthy character. The shady manager Campbell Ouiniette has needed to take drastic action at the Calgary Folk Fest, his biggest act having abandoned him to tour with a famous Icelandic pop star. Written in the form of found journal entries, this hilarious romp through the contradictions and outright absurdities of the contemporary Canadian folk fest circuit leaves no sacred cow untipped.

Split Tooth by Tanya Tagaq

Polaris Prize–winning musician and artist Tanya Tagak is internationally regarded for her powerful, inventive take on the tradition of Inuk throat singing. In her debut novel, Split Tooth, she tells the story of a young girl coming of age in Nunavut. Assembling poetry and mythology, autofiction and magical realism, prose fragments and drawings, Tagaq explores the impacts of sexual violence, the landscape of the North, and the experience of childbirth. With stunning language and fearless experimentalism, Split Tooth is a remarkable achievement.