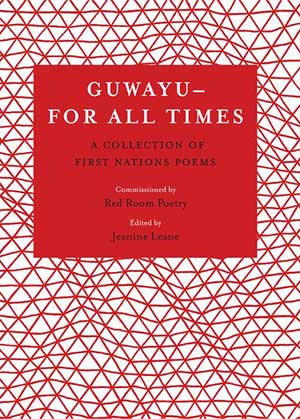

While the landmark anthology Guwayu – For All Times: A Collection of First Nations Poems (Magabala Books, 2020), edited by Jeanine Leane, refuses the “voyeuristic obsession with tragedy and trauma as the ultimate and only contribution of Aboriginal writing to Australian literary studies” (xix), at their most angered, the poems in Guwayu “sing for the massacres that litter our lands” (Ali Cobby Eckermann) and recall “Connected sites of significance [that] have disappeared” (Lorna Munro). These are poems enclosed within a brutally violent colonial history that has actively sought to exterminate Indigenous peoples and sever Indigenous cultural connections to place through, as Brenda Saunders makes clear, barbarous means:

While the landmark anthology Guwayu – For All Times: A Collection of First Nations Poems (Magabala Books, 2020), edited by Jeanine Leane, refuses the “voyeuristic obsession with tragedy and trauma as the ultimate and only contribution of Aboriginal writing to Australian literary studies” (xix), at their most angered, the poems in Guwayu “sing for the massacres that litter our lands” (Ali Cobby Eckermann) and recall “Connected sites of significance [that] have disappeared” (Lorna Munro). These are poems enclosed within a brutally violent colonial history that has actively sought to exterminate Indigenous peoples and sever Indigenous cultural connections to place through, as Brenda Saunders makes clear, barbarous means:

[. . .] Cleared forests, squared

the land into parcels bound with wire. They drove sheep

onto patchy runs, planted seed in a land with no seasons.

They gave new names to our rivers and creeks. New laws

defied our old beliefs, sent starving families drifting

off Country.

How to speak of the many documented genocides in Australia without the tragedy of dispossession wholly defining narratives of Indigeneity? How to voice Indigenous truths from within the colonial episteme?

Alongside other recently published anthologies of Indigenous poetry, Guwayu – For All Times stages an incandescent challenge to the Australian settler project. Similarly to Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today, edited by Alison Whittaker (UQP, 2020), and Homeland Calling, edited by Ellen van Neerven (Desert Pea Media, 2020), this anthology also creates space in which to deploy “innovative, astute and transformative literary intervention[s] that extend[] beyond the boundaries of despair, nostalgia, romanticisation or lamentation for a ‘prehistoric, ahistorical past’ or a doomed future” (xix). In this book, the tones are frequently celebratory and, at its most thrilling, Guwayu – For All Times deploys texts in First Nations languages; other poems mobilize Aboriginal English and engage in code-switching or otherwise explore (and problematize) the lyrical possibilities of English as colonizer’s artefact:

into a floral jar of untitled claypans and annotated spinifex

inhaling burgundy-stained pages of handwritten

riverbeds

silently, incessantly

quilling louvred hours of jaundiced memories

by the rising ceremonial seas of ante merediem

echoing curlews ribbon my desiccated tongue

mirroring speech

Yvette Holt’s imagistic explorations of land-as-text gesture toward nonsettler modes of apprehending and do so “quite lucidly, most insanely.” For poets like Holt, it seems that when reading unceded lands, Indigenous subjects are to remain locked into performing as if mad and displaced outliers, vocalizing depth structures of place from positions of material, systemic, and internalized exclusion.

Each of the thirty-six Indigenous writers in this book works from a position of displacement explicitly underwritten by the fact that “This was and always will be Aboriginal land.”

Editor Jeanine Leane asserts elsewhere that “whiteness, like the margins of otherness it defines, is a socio-cultural construct. And margins . . . are locales of agency, resistance and change” (Overland, #241). Guwayu – For All Times contains savvily tendentious maneuvers, and each poem in the book advances an ethical, engaged dissidence. Each of the thirty-six Indigenous writers in this book works from a position of displacement explicitly underwritten by the fact that “This was and always will be Aboriginal land” (Celestine Rowe). In wresting bio-political narratives from the grasp of colonial commentators, so often an Indigenous poet’s work seems to involve reinscribing place with extracolonial mythic language. Paul Collis’s “Barka-Murrdie (Darling, Black Person)” is a paean to the waterway that has long centralized Barkindji lives and culture, overwritten and erased by an imposed English pronoun (the “Darling River”):

Barka, Barka, murrdie Barkindji murrdie

My darling, my darling, black Barkindji person

Nga, kappa.

I will follow.

Collis’s gestures remain an exemplary complex of eco-poetic, political, genealogical epistemology, and his text speaks of relationality that performs to culturally specified logic. The same may be seen in Adrian Webster’s “Baladjarang,” written in the Gumea Dharwal language and rendered in English as:

I look at the trees, I see myself

I look at the rocks, I see myself

I look at the water, I see myself

I look at the birds, I see myself

I look at the country, I see myself

I look at myself, I see my old people

In these ways, this remarkable anthology reveals plausible syntactic possibilities for liberating narratives of Indigenous identity from the colonial project, and this work remains both symbolic and linguistic (of course). As Jeanine Leane asserts in her poem, “Yanha – Mam – Birra – Release”:

The space of my emptiness is a chasm so deep so wide

I’ll fall to endless nothing without your words to cross it.

Guwayu is a Wiradjuri word that means “still and yet and for all times” (xi). Very clearly, this is a book of constitutional linguistic crossings into possibility, a book that demonstrates the fruits of languages laboring toward remembering (and indeed remembering beyond) the historical and persisting atrocities of colonization. More than performing the critical work of intervention, then, this alliance of voices presents the possibility that “no time is ever over [and] all times are unfinished” (xi).

Herewith, a rapprochement of Indigeneity in Australian sovereign contexts is very likely to be the foremost literary, cultural work coming out of this country in the early to middle twenty-first century.

Sogang University (Seoul)