Zen Cho has had a very, very productive year.

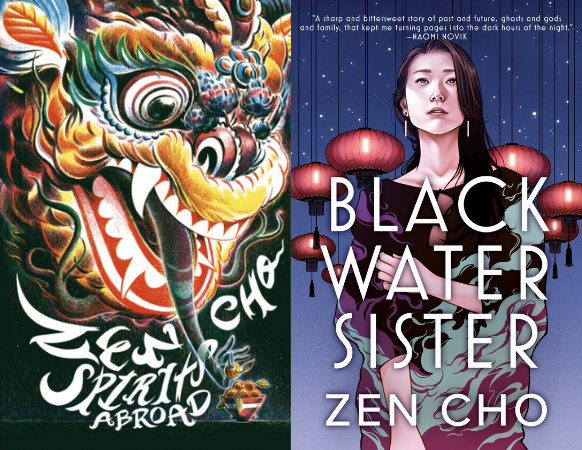

In 2020, the world welcomed The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water, a rollicking wuxia novella that turns history (and the laws of gravity) on its head. Just a year later, we get Black Water Sister, an intricate family drama disguised as a spooky, supernatural romp across Penang, Malaysia. And, soon after, an expanded reissue of Spirits Abroad, a 2014 blockbuster story collection featuring tales of uneasy coexistence between spirits, humans and everything in between, as well as the Hugo Award-winning novelette, If At First You Don’t Succeed, Try, Try Again.

Cho sets her stories in a variety of backdrops, blending small, domestic magics with a distinctly Southeast Asian flavor. Humming underneath her fantastical worlds is Cho’s deft skill with weaving complex human relationships and her characters’ pursuits to become more themselves. In “First Witch of Damansara,” the opening story in Spirits Abroad, the main character with a “mind like a high-tech blender” comes to terms with her lesser inheritance in a magical family.

Frequently, characters in her books hover on the margins, falling short of what is expected of them: humans tumble into love with the uncanny, girls are isolated by cruel uncles and long-dead aunts, an immigrant is caught between her past and future, while a would-be dragon grapples with its failure to ascend.

Often, those who fail uncover a new way of being, while others succumb to the seductive lure of magic’s potential to repair, as in “The Fishbowl,” where a girl makes a bad bargain with a carnivorous fish. But magic in Cho’s fantasies is very rarely the solution—usually, it’s the problem—which is why so many of her characters struggle with the knowledge that fitting in has a personal cost.

Over video call, we discuss her books Black Water Sister and Spirits Abroad, the domestic mundanity of the magical worlds she’s built, why she doesn’t believe in ghosts (though they almost definitely believe in her), and choosing who you want to be.

Samantha Cheh: When I first read the first version of your Spirits Abroad collection years ago, the magical elements were what drew me in. Looking back at them now, I’m struck by how domestic these stories are.

Zen Cho: Partly why Spirits Abroad has got such a domestic focus is that I basically used to draw quite a lot from my own life and experience. I was writing this in my mid-20s, and I would say I had a very sheltered childhood, but part of it is also that I’ve just always been interested in domestic stories: small scale, set amongst a particular community with their own dynamics and tensions.

I’ve just always been interested in domestic stories: small scale, set amongst a particular community with their own dynamics and tensions.

Then there’s the fantasy elements of the genres I grew up reading. I was inspired quite a lot by these great British children’s fantasists like Edith Nesbit, Diana Wynne Jones. Their children’s books tended to have a domestic setting —it’s mundane fantasy that’s very rooted in the everyday world. That was the kind of fantasy I like reading, so it was the kind of fantasy I was writing

You know, with the stories of Spirits Abroad, I found my voice. I see it as almost a lifelong project to combine the books that I loved growing up—mostly British books, with some Americans and Canadians—and my own experiences growing up in Malaysia, and our local culture. In Spirits Abroad, you can almost pick them off: that’s my orang bunian story, that’s my orang minyak story, that’s my pontianak story. I was going through all these local myths and folklore, thinking what can I do with that? It’s interesting because I think Black Water Sister is really the first time that I’ve been able to kind of express very similar themes, but in a novel form.

SC: A lot of your work is actually very literary—I know we make a lot of bones about this term, but it’s pretty clear that most genre fiction relies on plot for a backbone. But something like Black Water Sister, if you just take out the fact that Jess is being possessed by her dead grandmother, what you would essentially get is a family drama.

ZC: One very depressing reading of Black Water Sister could be that she’s just imagining all of it. I think it’s actually written in such a way that you could just about take that interpretation. Although I do read literary fiction and often enjoy it, one reason why I’m not a literary fiction writer is that I quite like a happy ending. Literary fiction writers can say what they want, but it is a genre convention that those books don’t have happy endings. If it does have a happy ending, that’s unusual.

Commercial and genre fiction are different. Obviously, there are books with sad endings, but ultimately, commercial fiction is all about delivering a pleasurable experience, which is what I’m more interested in as a writer and a reader. It’s quite hard for me to say precisely what it is that fantasy gives me, but one way of thinking about it is that it unlocks my imagination. It gives me a sense of freedom to explore the ideas that I want to explore.

I think it’s that distance from reality that I’m often seeking, maybe because my idea of literature, my idea of books, was something that was completely removed from real life. For me, there was a really big gap between my real life and what I was reading in books, and my work tries to kind of reconcile and bring them together.

At the same time, I really like the sense that this is a world that’s completely separate from ours. Genre often helps create that distance, whether it’s fantasy, historical, or romance. Romance takes place in a different emotional world, even if its plot takes place in what’s purportedly our world. To some extent, this is true of all literature: it’s kind of all in its own created world, but that distance just kind of feels right to me in a way.

SC: In both Black Water Sister and The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water, there is a sense of the characters being very in tune with the magical world, and living close with the supernatural to the point of mundanity. Is that quality connected to your love for the work of British fantasists like Jones and Nesbit?

ZC: I’ve never consciously drawn that link between those British fantasists and what I think inspires my more mundane books, but I think of Black Water Sister and Spirits Abroad as drawing on a Malaysian—or I guess to be specific, Chinese Malaysian—culture, where there’s very much a sense of the supernatural being just part of everyday life.

SC: Just out of curiosity, do you believe in ghosts and all that?

ZC: No, not really no. Maybe that’s why I find it quite interesting, quite charming. I’m very easily scared of horror films, not necessarily because I think it’s gonna happen, but there’s a space of doubt. I always say that my attitude to spirits is I don’t believe in them, but I’m just a bit worried they don’t care whether I believe in them or not. There’s just like that tiny, tiny doubt.

SC: Living in Southeast Asia, that doubt feels pretty inescapable, I’d say. This sense that there is always something kind of hovering just beyond your periphery.

ZC: I would say most of my family and friends from Malaysia believe in spirits. My best friend was really shocked to find out relatively recently that I don’t. How can you write that stuff if you don’t believe? I said I can only write that stuff cause I don’t believe, because if I believe I’d be too scared, right?

SC: Correct, cause then you’ll summon dunno what, right?

ZC: Right, right, correct!

SC: In Black Water Sister, you encounter the supernatural in the form of Datuk Kongs and possessive spirits, but you also depict things like trances, which are considered religious practices. When you witness them in real life, it can be quite shocking and it becomes easy to feel how close the supernatural feels to us. I think for Western readers, there’s a sense that these things are just fictional, but as someone who grew up here, these are things that are actually very familiar or I’ve encountered in my actual life.

ZC: With Black Water Sister, I actually watched YouTube videos of mediums going into trances for research, and I have to say that stuff is pretty spooky. When I told a lot of my Asian friends I was doing this, one of them was like eh, you’re not scared if you’re watching you’ll get possessed? I was like, well I wasn’t scared until now! [laughs] Obviously, on some level, I don’t really believe it’s going to happen, otherwise, I wouldn’t do it!

That said, writing stories that don’t include that magical element feels fake in a way. It’s like pretending there’s a world that doesn’t have these kinds of beliefs and occurrences in them. I do sometimes actually say in interviews that my work gets categorized as fantasy, but I’m very conscious that a lot of the time, I am writing about things that people actually believe in. Of course, I give it my own twist, but ultimately, if you’re writing about things that people believe in as though they are true, is that really fantasy? I don’t know.

I think it’s absolutely fine to write about like Chinese gods or whatever in this very mythological way, as a pure story, but at the same time, I always want it to kind of come off as something that is potentially real, even if you’re a skeptic. It’s partly a matter of respect, but it’s more a kind of realism. Being true to the emotional reality of living in Southeast Asia and living in that culture and having that kind of mindset.

SC: Your stories seem to look for a balance between the realistic and the fantastic, each varying by degrees. Do you see your stories as needing more realism with magic kind of thrown in, or are they more magical stories with big doses of realism?

ZC: I think the thing is that when I start writing something, there’s not a clear line for me between real and unreal. Obviously, in real life there is, but in fiction there isn’t, really. It feels very natural to me to kind of go from a mode of fantastical to less fantastical, or whatever. I don’t really understand writers who don’t do that, because it’s just how my brain works.

What interests me is the extent to which fantasy can literalize emotion. In that recent Harry Potter film, Fantastic Beasts, I remember a scene towards the end when the magicians go in to fix everything destroyed in New York. Narratively, that’s a complete cheat because magic should always make things more complicated, but what struck me about it was that it was such a great visual representation of the power of fantasy. This idea of repair made concrete.

I can see how it comes out in my work. There’s the wish fulfillment fantasy of having a direct connection with the past and the ability to communicate seamlessly with your forebears. It feels quite significant to me, for example, that in the “House of Aunts” (in Spirits Abroad), one of the aunts is actually Ah Lee’s great grandmother who she would never have known in her life, and Jess in Black Water Sister was estranged from Ah Mah until she starts talking to her in her head. My parents brought us up speaking English, which meant I couldn’t really communicate with my grandparents because they spoke dialect. In a way, it’s quite a personal fantasy that you can have this kind of connection with the older generation through magic.

SC: What was really interesting is that though a lot of your characters are slightly displaced from their worlds, they retain this very strong awareness of what their place in it should be. They’re characters in limbo, Jess especially, but also the protagonists in “Odette” and “The Fishbowl.” They are keenly aware of their place in the world, of where they’re supposed to exist, but they cannot quite seem to inhabit those kinds of spaces properly.

ZC: If you grew up in Malaysia, you can kind of have that experience even if you never leave the country. I grew up in an English-speaking family—that already makes you kind of unusual, because the majority of the Chinese Malaysian population primarily speaks dialect or Mandarin. If you’re English speaking, then you’re a minority in the media you consume. And then in Malaysia, you’re also like a minority but like a different kind of minority, right? At the same time, you can live in neighborhoods that are majority Chinese, you can go to schools that are majority Chinese, you can end up working in a workplace that is majority Chinese. Then you also have this awareness of a wider world— I’m thinking of Hong Kong, China, Taiwan—where you are a dominant group but not the dominant group, right?

In Malaysia, there’s such strong pressures and ideas around what it means to be Chinese.

Mentally, I’ve always had this sense of displacement or disjunction, and a kind of clarity about what I should be but just wasn’t. I spent a lot of my time living in fictional worlds as a child, that’s something that’s always been kind of part of my own self-conception.

But also, I guess, my background and life experiences all contributed to that because I moved around a lot as a kid. We lived in America for a couple of years then came back to Malaysia, but then my parents decided to send me to Chinese vernacular school because they thought it would be challenging for me. I didn’t speak any Mandarin okay! It was one of the worst experiences of my life. No shade on my classmates or whatever, but it’s just not a friendly experience.

SC: Oh, it’s horrible.

ZC: Yeah, the pedagogical approach is not nurturing, let’s put it that way.

SC: Recently, I found out that in one of the schools, they label the classes as literally hao (good), zhong (middle) and chor (bad), and I was just like, are you serious?

Zen Cho: Straight up! It makes sense to me. My first day in Chinese school, I was sitting there and the teacher who taught English asked me: Can you speak Mandarin? No. Oh, well can you speak Malay? No. She’s like, What are you doing here then? Then I was thinking, I’m eight years old. I don’t get to choose where I go!

It’s interesting because, in Malaysia, there’s such strong pressures and ideas around what it means to be Chinese. There’s a lot of language shaming—if you speak English, you’re not really Chinese, I got quite a lot of that from the adults in my life. There’s this kind of specific insecurity that comes from being Chinese in Malaysia, which pushed me to engage with the idea of who I should be? Who am I? Who am I not? The kinds of ways in which you fall short of that ideal of whatever it is you’re supposed to be, and being able to reconcile with it.

My attitude is I choose to be who I am, and this is just the way I am. So if I’m banana, I’m banana!… Like, whose idea of Chineseness am I living up to?

My attitude is I choose to be who I am, and this is just the way I am. So if I’m banana, I’m banana! I don’t have space in my life to get better at Mandarin right now. Like, whose idea of Chineseness am I living up to? Actually if you think about it, Mandarin was not the first language of any of my grandparents, they all would have spoken dialect as their first language. My maternal grandmother was Peranakan as well, so all her brothers went to English school. A lot of that experience has fed into my thinking about identity and having quite a strong sense of that.

SC: I think you definitely see it a lot with Jess in Black Water Sister, and to some extent, Byam in your novelette “If You First You Don’t Succeed.” These characters don’t quite live on the margins, but they’re constantly narrating to themselves: I am supposed to do this, and this is what is expected of me but because of whatever is wrong or off about me.

ZC: One thing that I’ve noticed as well in my work is that I have this sense that it’s fine to be that way. If you think of the imugi Byam in “If At First You Don’t Succeed,” it lives as something that it is not, and there is something wrong with that state because they should be a dragon. Byam doesn’t use a proper name or pronouns either because it doesn’t necessarily think of itself as a full kind of being. In a later sequel, when Byam has ascended, I use the pronoun “they” because now that they’re a dragon, they get to use a human pronoun. They obviously merited a human pronoun before, but that’s just kind of how they felt about themselves—that this was as good as it was gonna get and all they deserved.

I do write characters where ultimately you get to choose who you are. In True Queen, for example, Muna, the main character, accidentally gets split up from her other half, but she ends up choosing to stay who she is. Quite a lot of my characters have multiple names, and they get to kind of choose who they are that’s legitimate.