Poetry has always existed as humanity’s port in the storm and the keeper of our histories, before and after we began putting language to stone and pulp. I have always been drawn to the lesser known, and even yet-to-be discovered, poets, perhaps because in my mind, poetry encompasses so much more than simply its dictionary definition. To me, and many others, the creation of poetry encompasses infinite possibilities and, just each of us, holds a multitude of truths.

As the past two years have dumped an endless deluge of fear, sickness, anxiety, and grief upon the world, the poets march steadily forward. Even among a time when so many have had to temper their joy at their first books arriving in the world, or those who put out a new book with the nostalgic-sad tinge of reading tours past, we kept writing, publishing, adapting to virtual events, and amplifying each other’s successes. So many books, no matter how unsung by an industry machine designed to swallow all but the most known of the mainstream, are lost to the din. The small presses are often those who make the most daring decisions and publish the most diverse array of poetic voices, but whose reach is much narrower, so let us celebrate this—very small—sampling of brilliant collections you may have missed this year.

Gumbo Ya Ya by Aurielle Marie

If the ghost of Zora Neale Hurston could haunt a poetry collection, it would be Gumbo Ya Ya, which won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize in 2020. Obvious homage is paid to Hurston, especially Mules and Men, with the raucous chatter of Black voices and folklore bursting from Marie’s poems, placed firmly in the Deep South and all its dangers, glories, and inherent contradictions for a queer Black femme who must navigate the choppy waters of racism and patriarchy while so full of a love for her people that can so often lead to an even deeper grief as this country steals their lives. But this collection is, like Hurston herself, a loud, audacious celebration of Black people, no matter who is looking.

If God Is a Virus by Seema Yasmin

Perhaps you caught Dr. Seema Yasmin on CNN or you may know her from her award-winning collaborative book Muslim Women Are Everything. You might have missed the Emmy-award winning health journalist and epidemiologist’s first full poetry collection was acquired by Nate Marshall at Haymarket. The ironic part is Yasmin’s public success helping disseminate the factual information about the coronavirus’s effects likely overshadowed her poetic work based on her research on the Ebola epidemic in the U.S. and West Africa. The poems are often narrative, and spare, but cut as deeply and cleanly as the scalpel in a steady hand. Also encompassing the experience of a modern Muslim British Indian woman scraping up against patriarchal expectations of her culture, this collection is not to be overlooked.

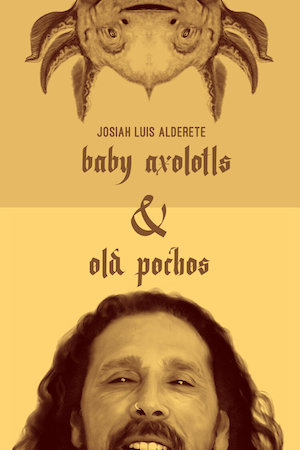

Baby Axolotls & Old Pochos by Josiah Luis Alderete

Nothing is better than discoveries in bookstores, especially those founded by poets, but when coming upon Josiah Luis Alderete’s debut collection at City Lights in San Francisco, I was delighted to find out he was also worked as a bookseller at the store. The collection itself defies definition as the poems embody the ethos of sin fronteras that many Latinx poets from the Southwest/West work within and around. From the tangle of Spanish, English, and Spanglish to Indigenous religions to his Northern California city home, Alderete digs into every part of his cultural inheritance and identity with playful wit and welcome.

It Was Never Going To Be Okay by jaye simpson

A deeply tender collection, It Was Never Going To Be Okay is Two-Spirit Oji-Cree poet jaye simpson’s pilgrimage to collect and intentionally arrange the pieces of self left fragmented by a lifetime of marginalization by family, religion, country, and colonial cultural expectations. Loss is a constant theme and keens throughout the book: loss of friendship, loss of their people’s historical embrace of Two-Spirit individuals, loss of their home, their people’s land, of tribal memory. Using language like the thinnest, sharpest needle upon metal, simpson etches an eloquent elegy of individual and collective grief.

808s & Otherworlds by Sean Avery Medlin

Rappers ascend into capitalist gods and crash back to Earth as burnt-out stars and the Arizona suburbs rise up like a Mesoamerican Valley of the Kings in Sean Avery Medlin’s trap opera poetry collection, where he conducts the becoming/making of his Black and gender-fluid identities, assembling and disassembling inherited mythologies of Black masculinity from a history of the U.S. slave trade, the performance of hood narratives in rap, and observing his own immediate family. Their poems take on a range of pop culture from Kanye West’s betrayal as a Trump supporter to a lecture on the Middle Passage delivered by X-Men’s Storm and keep you riveted from start to finish.

Philomath by Devon Walker-Figueroa

It’s been a strong year for Latinx poets writing about growing up in rural small towns (re: Even Shorn, Isabel Duarte-Gray’s collection about rural Kentucky) where the collective American imagination sees only as white spaces, a level of erasure and ignorance that our white supremacist systems would rather keep firmly in place. Luckily, the poets will not let us forget we exist everywhere.

In Philomath, Devon Walker-Figueroa maps out a journey beginning in the Oregon town of Philomath and its inherent small-minded, small-chance, small-town traps. Amongst the pressing need to escape, Walker-Figueroa sets her poems with the beauty of the land against the brutality of the people who now live there.

Iron Goddess of Mercy by Larissa Lai

Collections centered on modern anti-colonial retellings of mythology and subvert traditional forms are hands-down my favorite poetic genre (Is it even a genre? Who cares, I’m making it a genre). Larissa Lai’s Iron Goddess of Mercy uses a hybrid epistolary and haibun, a Japanese form of travel writing/prose poem ending with a haiku. If you’re confused, it’s basically poems written as letters ending in haikus told from the point of view of the Furies, who are, of course, furious about everything from the violent decay of colonial capitalism and its wars, the unwanted and refused refugee’s journey, whiteness, patriarchy, all the good stuff. But wait, there’s more! The collection is comprised of 64 “fragments” to correspond with the 64 hexagrams of the I Ching. Lai is a wildly inventive and uncompromising poet.

Field Study by Chet’la Sebree

Chet’la Sebree’s Field Study is unexpected in the way that a book-length lyric poem comprised of broken segments based on a Black woman’s exploration of self after the end of a years-long relationship with a white man would be. Sebree’s integral question is an important one: how, exactly, have Black and Brown people have been so conditioned to seek out whiteness in all aspects, especially romantic love? It brings into question what about our most intimate selves is truly us or instead a mere reflection of our racial conditioning. Sebree uses pieces of anecdotal narrative interspersed with quotes from writers and intellectuals and seemingly disparate asides to probe at how an identity is formed and with a single action, swiftly unformed.

Mother/land by Ananda Lima

We need more Brazilian poets to be recognized in the U.S., so Ananda Lima’s first full-length collection, Mother/land, is a welcome addition. Interrogating the liminal space of place as both mother and immigrant, Lima’s poems are full of the many small, but dear, longings and confusions of mentally existing in two countries at once and the separations between familiarity, families, and new experiences. She is masterful at tasking us look more deeply at the seemingly mundane, from making a peanut butter and jelly for her son to cutting her hair too short. Lima writes in a variety of forms throughout the book, giving the overall effect of nonstop movement, which pairs well with the almost-dreamlike tone of the subject of travel.

All the Given Names by Raymond Antrobus

The relationship between mother and son is a subject not often found in poetry in any great depth, but Jamaican British poet Raymond Antrobus gives it his due in All the Given Names, knowing that even though the more-absent and sometimes unlikable father is who men are supposed to base their identity on but it is the mother who is much more present and alive throughout the collection.

While many of the poems also ably tackle the ever-thorny question of identity when one is of mixed heritage, both culturally and racially (Antrobus’s father is Jamaican, his mother English), he comes back to his mother in a varied spectrums—as a petulant teenager testing boundaries, as a young man trying to bridge the distance between her love and adulthood, and as a grown son who can see and appreciate her for all she is and won’t be.