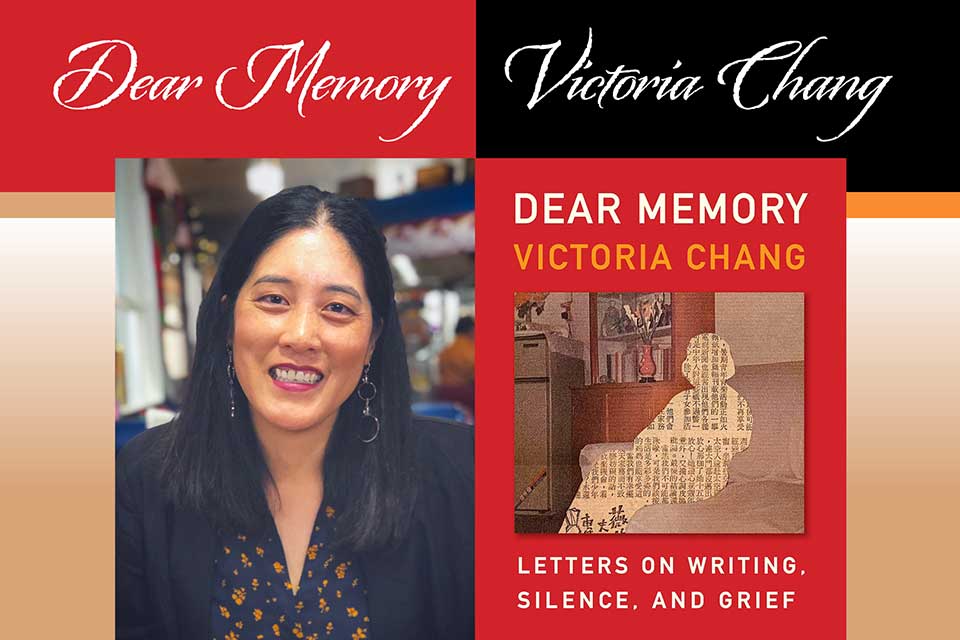

Victoria Chang’s new collection, Dear Memory, expands the field of the memoir for readers to explore a full-color archive of family photos and historical documents collaged between lines of poetry and letters. It prompts us to ask, with her, What composes a life and what makes of life art? What makes of memory history, and whose history, and how do we survive loss?

We might expect the author of five books of poetry and two children’s books to incorporate the lyric in her first book of nonfiction, but Chang goes further. If her memories arrive at times as poetry, she denies them the protection of a poem. For instance, at the end of a letter that begins, “Do you remember those Fridays in gym class . . . ,” she realizes that memory may be “the exit wound of joy.” Such insights pierce us before we can register surprise. Elsewhere, she covers her mother’s mouth with three Mandarin characters in the photo on her certificate of naturalization, inserting her reservation into the official record along with her daughter’s grief.

I reached out to Chang, moved by this book’s innovative form. “It was always my goal as a writer to be able to make whatever I want,” she told me via Zoom video hosted by the low-residency MFA program at Antioch University, which she directs. The winner of a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, the PEN Voelcker Award, a Sustainable Arts Foundation Fellowship, a Lannan Residency Fellowship, and a Katherine Min MacDowell Colony Fellowship, among other honors, Chang has earned her creative freedom. It’s how she enacts it in this debut that creates access points for others to relate, find, and shape their own stories.

Those familiar with Anne Carson’s Nox or Float will recognize kinship in Dear Memory’s movement between texts and images, songs and sentences, elegy and origination. For me it conjured specifically Carson’s translation of Sappho’s fragments, If Not, Winter, which is riddled with open brackets that mark censored, destroyed, and lost lines from Sappho’s poems. They function both like tiny tombstones where readers might mourn the voice that once filled them and windows beckoning us to peer beyond the veil of death and invoke new forms of communication.

Amy Wright: Dear Memory inhabits a space between prose and poetry, memoir and cultural criticism, linguistic and visual art, which is neither one nor the other but an alternate form altogether. At one point, your speaker describes the “space between” as “where I live.” Will you elaborate on how the form of the book illustrates the process of being shaped by living between cultures and languages?

Victoria Chang: Well, I think you’ve just identified the challenge I had with this book, in that it arrived organically and ended up being a little bit of everything. I started writing the letters, but then later found my mother’s interview, then added photos, then wrote the small poems on the photos, then started working visually with cut paper. At the end of the process, looking back, I think the book is its own kind of form. It is form within its formlessness. It inhabits its own space in the way that my own identity is often liminal and chameleon-like, trying to find itself while getting lost. I also tend to deconstruct everything, question everything naturally, perhaps because although I am American, I grew up in a Chinese/Taiwanese household.

Wright: Why did your upbringing prompt you to question and deconstruct everything?

Chang: When you grow up in a country, there are certain ways that country operates and that culture operates. But when you go home where another culture’s operating, there’s constant destabilization. You hear this a lot related to immigrants’ kids. You’re neither here nor there, but it’s more complicated than that. Confusion emerges from being bombarded with cultures and environments that are sometimes not only different but opposing. When you walk from one into the other, naturally you start questioning yourself because you just came from a culture that was operating in the opposite way. And being Chinese and Taiwanese is just different from American culture, at least in my Chinese and Taiwanese family.

My parents were highly educated. My dad had a PhD. Both he and my mother went to Taiwan National University, and so the quality of excellence was always part of their fabric. They demanded that from us kids too, which made me always ask a lot of questions and think a lot about things. So, it was partly that I inherited the minds of intellectual parents and partly that I was constantly navigating cultures. Now I think of these things as a luxury. Before, I thought I was a problem. That’s how I viewed it.

Only recently would I say I have begun to make art from coming out of those spaces, versus seeing myself, or the way I am, as a problem.

Wright: What shifted?

Chang: Age. I think something can happen to women when they hit their late forties. Also, my mother passed, and my dad had a stroke when I was in my thirties. My mom had pulmonary fibrosis when she was in her . . . I think it got diagnosed in her forties. So, both parents were ill at the same time, and then I had two small children and I was working hard in my job. I just couldn’t care about a lot of things that I used to care about. In many ways it was freeing, but there is something to be said about passing a threshold. But that movement from caring to not-caring started to sharpen my making of things. There has always been a little bit of that “I-don’t-care” to my art-making because I fall outside so many conventions.

I didn’t go get my MFA or publish my first book when I was in my twenties. I didn’t get a PhD in my late twenties. I didn’t do any of that stuff. I was doing different things. I’ve always been a go-my-own-way kind of person, but only recently did I stop thinking it indicated there were all these things wrong with me. I have more conviction now for making my own path. I will not bend my art for anyone or anything, and I’m happier now.

I think sometimes women don’t do something or do something in the way that other people want them to, but I’m at that age where I just can’t care anymore. I don’t care what you think, if you like what I make, I don’t care. I just want to make what I want instead of feeling badly about what I think, how I think, what I make, how I make it.

I have more conviction now for making my own path.

Wright: Dear Memory includes documents like your grandparents’ marriage license and your parents’ naturalization papers, between which are letters that question the performance of autobiography. How did you negotiate that territory?

Chang: We all wonder where we came from, but what’s fascinating is that there’s only so much history, real history, that any of us can know. We live a small set of decades if we’re lucky, and it’s impossible to know much beyond our own parents. In fact, how many of us really know our parents? Their deepest, darkest secrets? Probably none of us.

What is autobiography? Especially in today’s age of rampant social media, what is the self? Is there even a real self, or is everything performed, announced?

Wright: Quoting Jeanette Winterson, you say “the most powerful written work often masquerades as autobiography.” Again, you quote Winterson near the end of Dear Memory to conjure the chisel a writer “must make for herself” to sculpt the materials available to her. Do you think artifice can reveal a distinctive voice on the page?

Chang: We’re always performing all the time, but perhaps performance is also a part of the self, our identity. On the Winterson quote, it’s a paradox if you read the whole passage. On one hand, I believe putting some autobiography into writing is important because I sense that this is where the heat of the writing might come from, or heart (note that there’s only one letter difference between the two). On the other hand, I don’t think autobiography is enough, usually. The difficulty for any writer is how to make art that transcends autobiography. How do we make someone else care about what it is we’re obsessing about? Form, language, imagery, etc. can work toward this, of course, but this is the difficulty of writing anything that has autobiographical threads. Even a story that is truly unbelievable can be written poorly.

How do we make someone else care about what it is we’re obsessing about?

Wright: I agree and wonder how you recognize “art that transcends autobiography”?

Chang: I’m always interested in language at the language level, strange turns of thought that get me thinking about something new. So many of us are writing our own stories, you’d think we would have exhausted every way of writing, every song possible. Then a new song comes on and you think, I’ve never heard that before. I’m always looking for the kind of newness that intrigues me. It’s hard to name, but you know it when you see it, when you read it, that someone has made art out of their own story. There’s no formula. That’s the beauty of it, right?

Wright: Yes, but isn’t it tricky to be a teacher giving that lesson?

Chang: Well, you can give emerging writers tools. You can teach them about imagery and line breaks. In prose writing, you can teach them about characterization and structure. You can analyze pieces of literature and writing, but they do have to figure out how to do it themselves.

That’s the mysterious aspect of making something: something happens that you can’t explain. Yes, it’s a combination of the knowledge you’ve gained without realizing it, but there’s also something like a cloud that comes over you or you pass through, or you sit on top of or under.

When asked how a poem starts for you, poets say all the time “a sound, an image, a snippet of memory, a shard,” and it all comes together somehow. But we learn how to write by reading. We live in an MFA-industrial complex, but I think people have always learned to write by reading critically.

I think people have always learned to write by reading critically.

Wright: As a child of Appalachian reticence, I resonate with your line, “Silence was [my mother’s] second language.” How would you say your practice reading the unwritten and unruled language of silence informs your poetry?

Chang: I love that, “Appalachian reticence.” I think of poetry sometimes being more about the in-between than what is written, the silence versus what is spoken. It’s quite miraculous reading a poem that displays a lot of information and then going in and intentionally deleting random lines and how much more interesting the poem is. The paradox is that poetry seems to be, at least sometimes, seeking some kind of truth. Yet I don’t think a poem is supposed to find that truth but explore that seeking, the process, the mystery.

Wright: Dear Memory is subtitled Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief. At what point in the process did you know these themes would carry the book?

Chang: This was probably one of the harder things I’ve worked on in that I really had no idea what I was doing from the first word, and throughout the process I truly struggled. For me, this book is an X-ray into itself. If you look at the book, the internal organs, bones, diseases, are all apparent there for the reader. The title itself changed numerous times because the book itself was changing and morphing. It’s as if I were an archaeologist and thought I had found bones to a stegosaurus, but with each new bone I found, the animal changed, so that what ended up was a turtle. I just went along with the ride and did the best I could.

Wright: Several letters in the book are addressed “Dear Daughter” or “Dear Daughters.” How would you say this expression, versus other forms of communication, might guide the next generation?

Chang: The next generation(s) communicate quite differently than how I grew up. Going back to desire, I used to write letters, put them in the mail, and wait for letters back. Today, if my kid’s phone is running out of battery, she might say, “I don’t want to miss out on everything,” and what we may be talking about is an hour of a phone being dead. One hour, that’s it. There’s not a sense of patience or waiting that we had to deal with. I think this is great in some ways and detrimental in other ways. I know patience taught me a lot, and I think patience is a big part of creativity, making art, writing poems. Things take time.

I don’t know if this answers your question, but the idea that these next generations won’t ever be writing letters by hand is strange and interesting to think about—what’s gained, what’s lost. On the other hand, these kids can demand for change, they can organize quickly and effectively. They are not voiceless like I often felt I was. There’s a balance somewhere, though, and obviously all new rules, lots of land mines to navigate.

I think patience is a big part of creativity, making art, writing poems. Things take time.

Wright: Yes, I think these letters demonstrate and teach patience. I’m also interested in the paradox that you say to your daughters: “I had chalk in my throat most days.” And, although you later clear your throat, you say, “Please don’t follow me.” Were you stymied by models close to you?

Chang: In my family, it was always kind of implied that you don’t want to draw attention to yourself or talk a lot. That’s one of the key differences, I think, in our family culture and American culture. We were told to be quiet, to stay in the background, to be humble, not to brag, to stay behind the scenes. Then you go into the world, and you’re supposed to talk in class. The louder kids were the more successful ones. The most dynamic people become the presidents of the United States, you know. I was always the quiet kid who didn’t say anything in school, which continued well into my twenties, even though by nature I’m very chatty and extroverted and rambunctious. But I was told not to be that way.

By the time I made it into the workplace, I was surrounded by all these older white guys. I tried to be collaborative by asking people what they thought. Finally, one of them said, “Stop asking us. Make your own decisions.” It’s been a constant battle to reconcile that conflict because there’s also value in quiet, humble people with rich inner worlds. The interior is important! Yet it’s hard to integrate such contrasting cultures when you add the complications of being a woman, an Asian American woman.

Wright: One of my favorite lines in the book is when you close a letter to C by saying: “We often say night falls. I think the night rises. I think the bright falls.” This flip in orientation is surprising and subtle and seems to reflect a distinctly American lyric tendency to understate beauty, having been marketed by it for so long. How do you relate to the representation of beauty, especially when it dares to be profound?

Chang: This is so true. Our ideas of beauty are so forced down our throats at such a young age. Even in early learn-to-read books, we learn that the sun shines and the night falls. Things that seem easy/natural to many might not seem natural to me. I think this is nothing unusual, though. A lot of people in this country suspect what’s packaged and marketed to us. It’s our moral obligation to question the people trying to make money from human emotions.

It’s our moral obligation to question the people trying to make money from human emotions.

Wright: If you’ll let me continue reading that line, I notice the repetition: “I think the night rises. I think the bright falls.” Many writing instructors discourage the phrase, saying “I think” undercuts authority. Will you talk about how you negotiate, assert, and otherwise relate to authority?

Chang: “I think” does undercut authority. I don’t think of a piece of writing as wanting to assert authority though, personally. I also don’t think that writing instructors should be authoritative. Of course, it’s different if we’re talking about composition or creative writing, but I tend to be an open-ended instructor in whatever I do. I like to think about possibility versus rules. I like to think of the brain as an open field with different seasons and different flowers depending on the kind of wind that comes in, versus a fixed organ within the cage of a skull.

Wright: Do you think feminine authority differs from masculine, or does authority transcend gender?

Chang: Absolutely. I think of authority as being primarily masculine. This whole culture is masculine and dominated by toxic masculinity; this concept of domination is at every turn, and every time I feel it or see it, I have a desire to stamp it out. I tend to think about horizontal lines versus boxes or vertical lines. I think masculinity asserts itself in language on a daily basis. I think my own style of authority is more collaborative, query-based. I often like to ask people what they think, then ask questions that might get them thinking some more, then let them decide. Authority as conversation and group work, versus this is what I think and how you should do it.

Wright: Who or what has encouraged you over the years to trust your voice?

Chang: No one now that I really think about it, in the way that you’re asking. I’ve had some great teachers, but I think it’s also hard to tell students that they matter. I think feedback back in the day was more about the writing and less focused on boosting people up. As a teacher and parent, I tend to boost as much as possible while giving constructive feedback. Sometimes a little encouragement goes a long way. “You matter” is hugely powerful.

I’ve always had a lot of conviction. The more people tell me I cannot do something or that my voice doesn’t matter (either verbally or silently), the more I want to make my voice heard. I have a very strong sense of personal and collective justice. And I never give up. And by give up, I am often not aiming for what others are necessarily aiming for. I think we all have something that we’re trying to do, but it’s hard to know what that is, so the idea of being a creative person or living a life of creativity is to just keep going, whatever happens. The act of making for a writer is often an act of living, of survival. For me, writing has saved my life more than once.

Sometimes a little encouragement goes a long way. “You matter” is hugely powerful.

Wright: In the only letter in the book addressed “Dear Reader,” you write, “More and more, I think writing is not a choice but an act of patience. An act of listening to silence, into silence.” I wonder how this awareness translates in seminars and workshops that you teach. Are there ways you encourage emerging writers to listen deeply or practice patience?

Chang: Absolutely. I think that writing and the creative life is for the long haul, meaning it is for life. It is life. I know that might sound idealistic or hokey, but the joy is in the making, the creation, the discovery, the process. I truly believe this. None of the publications, accolades, responses from readers can truly make a writer happy. Finding joy in the process of creation makes me truly happy, even when it’s hard or not going well. Through the struggle, I hope to learn how to become a more interesting artist and person.

Poets of longing are always more interesting to me as a reader than, say, poets of knowing.

Wright: In the concluding letter in the book, you muse that “Maybe the unspoken can lead to the widest imagination.” Will you give an example from your life or writing that supports that potential?

Chang: I think that I am constantly obsessed with what I have, what I get, what is concrete. Perhaps that’s the function of being born into a capitalist economy. But oftentimes, I think the most interesting writing, imagination, etc. can emerge from not having, never getting, and never having the potential to get. We all have those things that we pretty much know we won’t ever have . . . whether it’s simple like a different hair color, or a different body, or curly hair, or even more serious things such as health (if you’re sick) or a lover (that one might desire) or to live forever (if that’s desired). Out of this knowing is desire, and I always think that desire can lead to the widest and wildest imagination. Poets of longing are always more interesting to me as a reader than, say, poets of knowing.

September 2021