Growing up, once a year my anneanne (maternal grandmother) would visit my family in our suburban home in Ohio. Before returning to Istanbul, she never failed to stock our fridge with sigara börek, a puff pastry filled with cheese and rolled into the shape of a fat cigarette, as its name suggests. For months after, we cherished those treats made with love, savoring each crunch. The longer we could make them last, the longer we could hold onto a culture we struggled so hard to maintain in the Midwest.

Fellow Turkish American Mina Seçkin captures this third culture sentiment in her captivating debut novel, The Four Humors. Within the first few pages, I flashed back to my own summers spent in Istanbul. Once again, I was 18 years old sipping on black tea while taking the ferry across the Boğaz to go shopping for towels at the bazaar with my anneanne. For the first time, I felt seen in a piece of literature.

The Four Humors transports you into Sibel’s summer full of simit, cigarettes and secrets. A year after her father’s sudden death, Turkish American Sibel comes to Istanbul with the intention of visiting her father’s grave and caring for her babaanne (paternal grandmother) who has Parkinson’s. However, burdened with a chronic headache, she avoids grieving her father’s death by instead fixating on the Hippocratic theory of humorism and watching soap operas with her grandmother.

When her grandmother reveals a secret about her father, Sibel dives headfirst down the rabbit hole of her family’s past. Coated in endearing wit, Sibel takes us on her journey of catharsis as she begins to process her father’s death with the help of the rich oral storytelling of the women in her family.

On a chilly Sunday morning, I met Seçkin for Turkish breakfast at Antique Garage in Soho. Over sucuklu yumurta (eggs with spicy sausage), black olives, sour cherry jam and, importantly, thick sesame bread, we spoke about the unique Turkish identity, crafting authentic immigrant narratives and our grandmother’s remedies we just can’t seem to shake off.

Amy Omar: At what age did you first start writing? What did you write about? Were you always influenced by your family’s history and stories?

Mina Seçkin: I started writing in high school in an incredibly supportive poetry class. My early poetry mostly revolved around the female body, sexuality, and consumption. It wasn’t very narrative, but there was a lot of body and a lot of eating, two backbones of The Four Humors. But I never addressed a cultural and ethnic identity in these poems.

When I started undergrad at Columbia, I took a fiction workshop for the first time, but even then, I was still in this exploratory process where I began writing narrative fiction, but focused mostly on themes surrounding alienated, gently manic white American women with names like Annabelle and Macy. I was introduced to many incredible short story writers like Mary Gaitskill, Lorrie Moore, George Saunders and Denis Johnson. The narrative voice in these was so zany, fun, and entirely human in their exposition of the strange, but the characters were far and away from my experiences growing up and those of my friends, many of whom are also kids of immigrants.

I had trouble finding that voice in novels that were about the immigrant experience or stories about people of color. It was like white authors were allowed to employ this zany voice, but other groups didn’t have that liberty. Their stories were expected to revolve around hardship and trauma. I was also wary of writing a story where, by emphasizing the otherness of the character, I would further other, exotify, and alienate my characters.

Around my junior year of college, I started writing a story about a Turkish American girl trying to lose her virginity, and I knew, as I began writing, that I could tell this story without making such a big deal about the ethnic identity of the narrator. I did receive pushback—comments like, there’s too much going on here with ethnicity and culture on top of this plot and complicated character—but I kept going. I began writing about Turkish American characters then and haven’t looked back since. I don’t know if I ever will, to be honest.

AO: I know you started writing The Four Humors in 2014 on a trip visiting your grandmother in Istanbul. What was the initial spark and how has the story evolved since then?

MS: This novel started as a short story. I wanted to tell the story of a girl and her grandmother, specifically focusing on how the older generation, especially grandmothers, insist on taking care of the younger generation—even if they have life-threatening illnesses. During the summer of 2014, I was staying with my grandmother and my great grandmother, who was 96 and had Alzheimer’s and dementia. It was the three of us staying in my grandmother’s apartment in Istanbul and my grandmother was not only caring for her mother but also for me; I had a chronic headache all summer that proceeded to last a year and my grandmother was more worried than I was.

AO: Why was it important for you to focus on the oral history of your female characters, rather than male characters?

MS: It’s not about the men.

For a long time, and even now, women in Turkey and the wider Middle East were not customarily able to tell these stories because they weren’t given a platform that allowed preservation. Many of these women were not literate and whenever they did tell their stories, they were rarely documented or preserved. The reality is that history has always been written by men, so many of these female stories get buried within families and never get published.

It was like white authors were allowed to employ this zany voice, but other groups didn’t have that liberty. Their stories were expected to revolve around hardship and trauma.

The oral tradition is so prevalent in Turkey. I can’t even count the number of times the elders in my family have sat me down and told me dramatic stories of their past. This is why I needed the narrative frame in The Four Humors to be the grandmother and Refika sitting down and telling their stories directly to Sibel.

I knew I could have written a much easier book by not going into the past, but I felt I had to; I had a responsibility to give these women the chance to tell their stories. An easy story is also not interesting to me, and it would not have suited a setting as complicated as Turkey. At one point, I even considered writing the novel entirely in the past and from the point of view of the grandmothers, but ultimately, I wanted the novel’s emphasis to be about how receiving a family story can change you, and can make you, in the youngest generation, choose to live differently.

AO: You do a beautiful job of interweaving bilingualism into the novel, diving into the cultural meaning behind various phrases as a mechanism to show the presumably non-Turkish reader the cultural relevance each phrase holds. What role did bilingualism play in your development as a writer? Did your ability to speak in two tongues impact your English writing style?

MS: I’m obsessed with this topic because as soon as I became aware of the power of language, I realized how much people would make fun of my family’s English—including my own. I began to notice how my father, who can’t really speak grammatically correct phrases, has his own way of expressing himself in English. By not knowing the correct grammar or cliché phrases, he instead reaches for things with a different sentiment and tries to get to the root of the original communication. He’ll use a different word that conveys the sensory experience with even more precision and raw feeling. He ends up a poet! I’m really grateful for this—it’s always made me see the power and the fun in breaking the rules of language.

In high school, I read Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov, a novel about exactly this topic. I think Nabokov didn’t write in his native tongue and that’s why he uses surprising words that a native speaker wouldn’t necessarily use.

AO: What’s amazing is that modern Turkish is not inherently “Turkish”; it’s an amalgamation of Arabic, Farsi, Urdu, French, etc.

MS: Exactly! I’m really against the idea that language isn’t meant to change or that there is one way of expressing yourself in a language.

AO: Going into your novel, I knew very little about humorism. However, growing up in a Turkish household, I could especially relate to the bits of eating yogurt while on your period and the garlic concoction grandmother makes for Sibel’s headaches. In contemporary times when there is so much science around healing, why do you think these non-medical practices still persist? Why are they so comforting?

MS: When I first started reading about the four humors, I saw how they are still alive and well today, but in two different ways. One is the potions our grandmothers still make. The other is the more notorious wellness industrial complex, which takes the same narrative crafted by our grandmothers and packages turmeric for $80. Fundamentally both methods are not at odds with the other—the meaning of wellness has just become sullied.

The reality is that history has always been written by men, so many of these female stories get buried within families and never get published.

Wellness is actually about taking comfort in something, not about becoming your best self. It’s about whatever taking care of yourself looks like for you and finding comfort and joy in that routine, not perfection. For Turks and so many others, it’s about trusting your grandmother’s remedies, regardless of the lack of scientific data. I’m still convinced that I feel sick after going outside with my hair wet, so yeah, I often make sure my hair’s dry before leaving the house.

AO: There are several parts of the novel where Sibel, a Turk raised in America, is subject to a certain level of disconnect to Turkey and her relatives there. Sibel, like you and I, can be categorized as “third culture kids” not necessarily American nor Turkish. Could you speak to how this concept affected your identity as both an American and a Turk?

MS: I feel like when you’re a kid of immigrants, you have this second coming of age and that’s when you start reckoning with where your family comes from and how you fit into that world. I always think about the privilege of having American citizenship and being able to just go to Istanbul for vacation, but also feeling the effects of what is happening in Turkey because your whole family is there and is living under sometimes conditions that are difficult in various ways.

A few years ago, I was in Istanbul for the summer and my immediate family was about to return to New York a month earlier than me. I was initially excited to be on my own, but then I had this moment when I was in a cab with my sister and the driver started questioning us about our accents and where we were from. I was so overwhelmed—about my stay, about my relationship to the country, I started crying in the cab. What am I doing here? I remember asking my sister, why do I love this place so much when we’re not really from here?

One of the reasons I set my book in 2014 was because that was the first summer I was in Turkey going places by myself via public transportation. During earlier trips, I would be in a car with my family and recognize everything around me, but I didn’t have to use my own map and compass. That was the first summer I began to understand the city on my own terms.

A few years later I was in a translation workshop, and I stumbled across this writer Leyla Erbil in the library. She was one of the founding members of the socialist group, Workers Party of Turkey, and her novel, A Strange Woman, was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2002, but few family members and friends knew of her (they were not engaged with literature, to be fair). I was so struck by the voice of the protagonist who speaks her mind and who wants to do good, but also wants to talk about sex and is trying to fight her parents to let her do what she wants. Why weren’t more people talking about this woman?!

I’ve always been grappling with the fact that so much art and intellectual discourse is actively buried in Turkey, especially if that art is political or grazes against any taboo. And there are deep taboos in Turkey’s history, especially as it relates to how minorities within Turkey have been stripped of their rights and their lives. Over the years, my understanding of Turkey became different from my family’s—at least, I wasn’t as wary to engage with the country’s history critically because, in a sense, I had the freedom to. I also questioned whether I had the right. And I understood that within this, my being Turkish went hand-in-hand with my being American. That was the second coming of age for me.

AO: I find that Turkey is still a mystery to Americans. Are Turks European or Middle Eastern; religious or secular? Why do you think this is still the case?

MS: It’s funny—a few days ago, I looked at how readers had digitally “shelved” The Four Humors on Goodreads and I was both shocked and not at all surprised; the various shelves perfectly encapsulated the Turk’s ongoing racial identity quandary. It was shelved most as “Middle Eastern.” It was also shelved as “Eastern Euro,” “Asian lit,” and “Western and Central Asian.” Then there was both “BIPOC” and “non-American white fiction.” I say this as an example of how impossible it is to answer this question without diving into a long essay on identity, Middle Eastern history, and Western power—an essay I’ve been attempting to write for quite some time. For now, I’ll say that I do believe that the Turk has always been Middle Eastern, or, to be more specific, Western Asian, and the desire to be seen as European—which not every Turk has had—has only ever been an aspirational glimmer.

I’ve always been grappling with the fact that so much art and intellectual discourse is actively buried in Turkey, especially if that art is political or grazes against any taboo.

But for now, a little more about deluded Western aspirations and how they relate to assimilation, there’s this dish called manti, tiny meat filled pieces of dough served with a garlic yogurt sauce. Growing up, whenever my parents would describe manti to non-Turks in America, they would compare it to an Italian dish of ravioli or tortellini. I’d heard many other Turks in America describe it this same way, too. In reality, manti is a tiny dumpling—and the dish came from Central Asia. The meat is spiced. It tastes nothing like Italian pasta, and a lot more like East Asian dumplings. But Turkish Americans would insist on identifying it with a Western dish, perhaps aspirationally, but also perhaps because they thought that white Americans would like the dish more if it seemed Western. Many immigrants do this—I feel it’s Assimilation 101 to attempt to draw parallels with the racial group in power and not with the groups that are also new to the country and standing on undefined, shaky ground.

Anyways, it’s my dream to host a “dumplings of the world” dinner party and make manti!

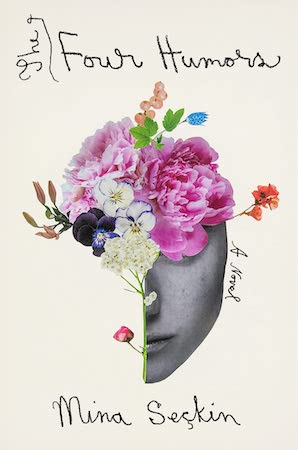

AO: The jacket of the novel was designed by Na Kim and illustrated by Ekin Su Koç. Can you elaborate on the significance of the cover and how you chose this design?

MS: Ekin Su Koç is a Turkish artist based in Germany. About six years ago, I randomly came across her artwork online and fell in love. I felt like her art visualized everything I was interested in writing about. Her style is very collage oriented and features maps, women of all ages and generations, body parts, and geography in this way that summons history. Her themes summoned everything in The Four Humors. I told Catapult about her work, and Na Kim, who designed the cover of The Four Humors, featured a piece of Ekin’s. I couldn’t be happier with the result.

AO: Why do you feel like this book is important to share in 2021?

There are still not enough Middle Eastern stories in America and the region remains vastly misunderstood, especially from a female perspective.

MS: In jest, my mom once said to me, “Middle Eastern girls don’t get to be depressed.” I wanted to write toward what is considered ugly in both body and mind, an ugliness that my narrator manifests as an American kid of immigrants spending the summer in her parents’ country, where expectations are both different and familiar. Melancholy, otherwise known as black bile, has been around for centuries: it’s mood disturbance, it’s depression, it’s something we all grapple with—either often, or at certain times in our lives. I wanted to represent this mental state as it would affect a child of immigrants, a woman, a person ethnically from the Middle East but American, too.

There are still not enough Middle Eastern stories in America and the region remains vastly misunderstood, especially from a female perspective. And I wanted to be honest and realistic—I did not want to create an entirely “good” character. I was very intentional about crafting a protagonist who was a young woman who is “unlikeable.” In many ways, Sibel is a disaffected millennial, who isn’t doing what she is supposed to be doing throughout the novel. She isn’t caring for her grandmother. She’s outspoken and also entirely in her own head. She’s a secret smoker. She doesn’t care for the shame that is typically associated with the female body. It’s still not common to see these sorts of female characters who are Middle Eastern and I hope to read many, many more.