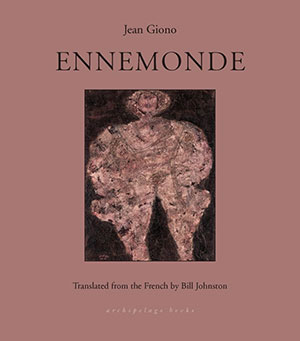

Written late in life, “Le Haut Pays” and “Camargue”—once again paired in the Archipelago Books edition of Ennemonde, newly translated by Bill Johnston—offer a microcosm of French writer Jean Giono’s postwar écriture. Here, Alice-Catherine Carls takes the measure of the renewed fascination with Giono’s works, marked by half a dozen new translations into English in the past five years.

Ennemonde’s Genealogy

When published in 1968 by Gallimard, Jean Giono’s Ennemonde et autres caractères (Ennemonde and other characters) had two nontitled parts, numbered I and II, no table of contents, and only a brief foreword containing a biography of Giono (1895–1970) and his own presentation of the book:

Ennemonde is a simple tale that develops certain characters surrounded by their landscapes. Clef-des-coeurs had appeared furtively through Deux Cavaliers de l’orage.[1] Here he loves and dies in glory. Ennemonde will know pleasure, after a perfect crime. She lives on, old, huge, but very clean, and she listens for the rain. Other characters organize their lives (and also their love life) with trees, wild bees, sand, cattle, and secretary birds (serpentaires, also called huppes). Only the gold coins lover is carried away by two dogs.[2]

By mixing episodes from both stories in the same sentence and linking at least one character to a previous work, Giono wove these two separate stories to the major threads of his work. And yet the link between both stories was originally inexistent. The 2021 Archipelago Books edition, newly translated by Bill Johnston, does not provide an introduction or a table of contents and shortens the volume’s title to Ennemonde; the reader is left wondering what the two stories have in common.

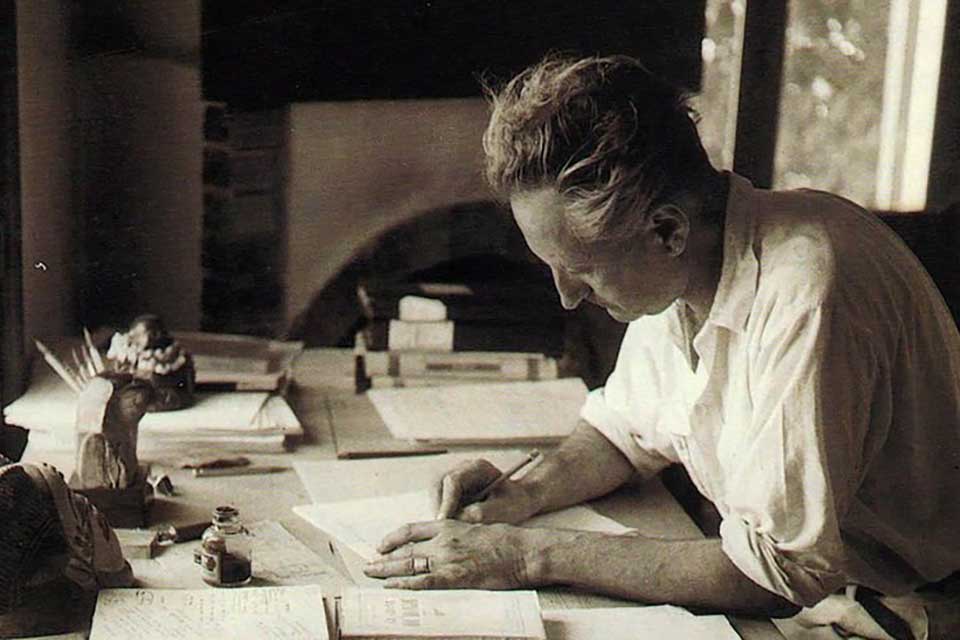

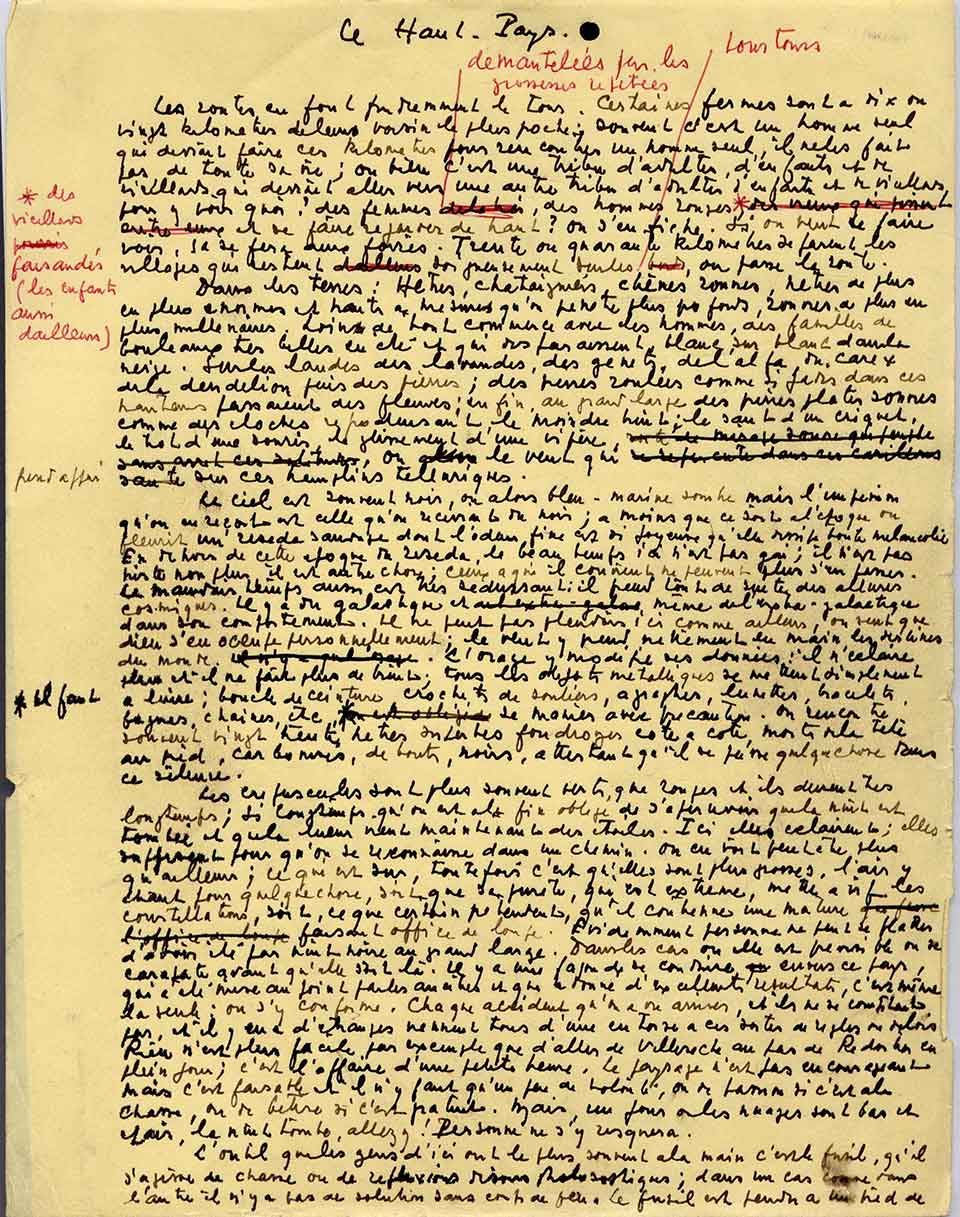

Ennemonde et autres caractères has an unusual genealogy. Giono wrote the two stories at the request of visual artist friends, to be published in their artists’ books. “Camargue” (Part II) was written in August 1960 based on a selection of one hundred photographs of Camargue by German photographer Hans Silvester for his first publication. Camargue was published in late 1960 in a German translation by Josef Keller Verlag in Munich and in French by the Guilde du Livre / Editions Clairefontaine in Lausanne. “Le Haut Pays” (Part I), featuring the region between Mount Ventoux and Lure, was written in 1964. It was published in late 1965 by the Paris art publisher Les Heures claires with eighteen lithographs by Pierre Ambrogiani, which were executed after the text was written.[3] While the relationship between text and image was different in both cases, Giono knew the work of these artists well, and he had written an essay about Ambrogiani’s Provençal paintings in 1961.[4] He wrote both texts rapidly, to take a break and “stretch” his mind from his novels.[5] He often used this multitasking strategy when stuck on longer projects or to clarify his perspective. Shorter texts allowed him to use a wide variety of genres and to write for a diverse public, from essays and travelogues to judicial reports, historical studies, and filmscripts.

Then Giono returned to his novels. In 1968, ailing and unable to complete his yearly novel, he sent Gallimard “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays”; they were published as Ennemonde et autres caractères. After Giono’s death in 1970, Ennemonde et autres caractères fell into relative obscurity until Bill Johnston’s present translation. The modest size of both stories helps explain the situation. Compared to the novels, which fill eight volumes of the famed Bibliothèque de la Pléiade at an average of 1,500 pages each, to which one must add two more Pléiade volumes gathering the Journal—Poèmes—Essais, the Récits et essais, and various theater plays and pacifist essays, parts I and II of Ennemonde et autres caractères are but a small fragment of Giono’s immense work. Yet, brevity being beneficial, “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays” are not mere writing distractions. They are a microcosm of Giono’s postwar écriture.[6] Furthermore, the similarities between them suggest interesting aspects of Giono’s personality.

Then Giono returned to his novels. In 1968, ailing and unable to complete his yearly novel, he sent Gallimard “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays”; they were published as Ennemonde et autres caractères. After Giono’s death in 1970, Ennemonde et autres caractères fell into relative obscurity until Bill Johnston’s present translation. The modest size of both stories helps explain the situation. Compared to the novels, which fill eight volumes of the famed Bibliothèque de la Pléiade at an average of 1,500 pages each, to which one must add two more Pléiade volumes gathering the Journal—Poèmes—Essais, the Récits et essais, and various theater plays and pacifist essays, parts I and II of Ennemonde et autres caractères are but a small fragment of Giono’s immense work. Yet, brevity being beneficial, “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays” are not mere writing distractions. They are a microcosm of Giono’s postwar écriture.[6] Furthermore, the similarities between them suggest interesting aspects of Giono’s personality.

Language and Translation

Not one to shy away from challenges, as readers may already know from his acclaimed literary translations from Polish, Bill Johnston chose for this, his third translation from French, a work requiring uncanny agility. A linguist by training, possessing a broad literary culture, Johnston has established himself since 1995 as one of the best translators of Polish prose and poetry with thirty books and over fifty shorter pieces. He has won numerous awards, including Three Percent’s Best Translated Book Award, the PEN Translation Prize, and the AATSEEL Translation Prize for his translation of Wiesław Myśliwski’s novel Stone upon Stone. Three of his translation awards have been for poetry, notably the 2019 National Translation Award in Poetry for his “epic foolishness” project, Adam Mickiewicz’s national epic Pan Tadeusz, which took him three years to complete.[7] After twenty-five years in the company of some of the most well-known Polish nineteenth- and twentieth-century authors, Johnston branched out and translated two contemporary French novels: Alain Mabanckou’s The Negro Grandsons of Vercingetorix (2019) and Jeanne Benameur’s The Child Who (2020). He is currently working on Charles Ferdinand Ramuz’s 1926 La Grande peur dans la montagne, Roger Martin du Gard’s Vieille France, as well as Wiesław Myśliwski’s Needle’s Eye and Maria Dąbrowska’s The Nights and the Days.

Johnston’s musicality allows him to hear pitch, tone, and rhythm. His eclectic choices of authors who range from classical to new voices indicate his instinct for powerful writing. One quality that he imparts to all his translations is a sense of textual movement. Whether the original text is slow and deliberate or furious and sparkling, Johnston’s translation is never static; it captures or even reveals the suspense and the passion present in the original work. Johnston describes his translation technique as “looking for the ‘voice’ of the author,”[8] much like an actor searching for his character; this allows him to remain faithful to the spirit of the text. These translation techniques are quite evident in Ennemonde, whose language Johnston calls “Southern French Gothic.”[9] The description of the secretary bird in part II illustrates his use of British literary and poetic traditions cross-fertilized by American English:

Now, along with the daylight the secretary bird enters the stage. He comes in with rapid steps: that’s why he’s also called the messenger bird; he has his quill tucked behind his ear like a bookkeeper, which is where he gets his name. In order to walk even faster, he uses not his wings but his ferocity, which he hardens like a lead sinker in his forward-leaning head; in this manner he drives himself onward like a Greek hero. He paces the sands like Achilles circling Troy. He’s a walking vulture destined to live in deserts. His life is pure Iliad. He has greaves on his shins. He’s gray as an ancient warrior, except on his flanks, where, like old trophies of plunder, he wears emerald, sapphire, and tarnished gold. For a long time now he’s been on the lookout for snakes – watching for the largest of them. He was waiting for the sun. The sun is here; he waits no longer, he attacks.[10]

Sensual and torrential are adjectives used routinely to describe Giono’s style. This “raw,” seemingly unfinished language, which sweeps along in an extraordinary profusion of details, is borne by accurate and detailed observation. French scholar Emmanuelle Lambert calls Giono’s language artisanal because of the quality and details of his descriptions and, “galloping” à la Stendhal, breathless, without a superfluous word.[11]

Johnston always reads the score of Giono’s voice correctly, without shying away from his own interpretation.

Johnston does a remarkable job of keeping the French sentences quick, flowing, and dense. He changes semicolons into periods and vice versa, occasionally redistricts paragraphs, merges two sentences to avoid repeating a verb, or separates two parts of the same sentence for added emphasis. He puts some translated words in italics for better cultural understanding when there is no such emphasis in French. Rather than writing notes for untranslatable words such as ubac or Ecole Normale, he gives a brief explanation in English—a felicitous choice. Sayings that take one word in French may take a phrase in English and vice versa. Whatever the case, Johnston always reads the score of Giono’s voice correctly, without shying away from his own interpretation. As for the biggest challenge, namely Giono’s frequent vernacular and colloquial expressions, Johnston succeeds in capturing their colorful, funny, familiar/unfamiliar fragrance: une tripotée becomes a barney, the old-fashioned buscatier a woodsman, la savate kickboxing. Nicknames, which Giono relishes, and place-names take us into another dimension. Johnston’s translations delight: a Dupuis nicknamed Bouscarle becomes “Wagtail (a kind of bird)” while other members of the Dupuis family include Sniffler, No-Work, Melchior, Automobile, Ironhead, and Anvil.

Johnston also translates local place-names; the bac du sauvage becomes “wild man’s ferry” and the tongue-twisting col de la Croix-de-l’Homme-mort “Croix de l’Homme Mort Pass”; when shortened by Giono to Col de l’Homme Mort, it becomes “L’Homme Mort Pass,” its present name, made famous for being on the Tour de France circuit since 1947. Other translators might have left some of these words in French. In his 1970 translation of parts I and II, for example, David Le Vay left nicknames and place-names in French, assuming that his readers would understand, which they probably did back then.[12] Johnston, who chooses to translate for a general audience, cultivates an immediate and full cultural understanding of the original text. Last but not least, Giono commandeered words straight out of the nineteenth century. Instead of binoculars, he talks about longue-vue, which Johnston translates by “spy glass.” The word monotone, which Giono uses fairly often, is translated either by “one-note” or “monotonous.” Perhaps, as Johnston modestly says, any good translator would catch the nuance, but it takes talent to know when to use which.

Parts I and II of Ennemonde et autres caractères have a particularly torrential, dense, and rapid style, as if thought shortcuts were needed to produce a condensed version of something much bigger. By comparison, Giono’s longer novels feel a bit slow, both in French and in translation, an interesting fact since Giono has been translated by many different and very competent translators. Through the rapid style of parts I and II, Giono crammed a full universe in small packages that require to be “unzipped” for full effect. For there is much to enjoy, from tongue-in-cheek jokes and cultural allusions to Giono’s silences, about which he warns the reader at the beginning of part II: “When mysteries are very crafty, they hide in the light; shadows are merely a decoy” (131). Thus language and style need to be decoded first, as they are a key to plot and structure.

Beyond Ekphrasis

As commentaries to visual artworks, “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays” had a predetermined format and audience and were expected to have at least an ekphrastic component. “Camargue” is more ekphrastic than “Le Haut Pays,” owing in part to the different relationship between art and text for both texts, and in part to the fact that “Camargue” was the first of the two texts. The first seventeen pages of “Camargue” are exclusively devoted to a description of the lagoon area, its physical characteristics and its fauna. The second half of the story is visually separated from the first and features the story of cowherds going back to the mid-nineteenth century and whose cumulative history creates a composite portrait. “Le Haut Pays” has a similar structure. It opens with an ode to a small region situated between Mount Ventoux and the Lure region, followed by an anthropological study of the local inhabitants on page 6. Ennemonde, the main character, is introduced on page 10, only to see her story dismissed from pages 15–60 with the humorous remark about her husband’s death, “The rest is commonplace and has no story attached.” Her story and that of her family then occupy the full second half of the story.

Giono’s inexhaustible and irrepressible penchant for storytelling caused him to transgress his assignment in both texts and to use the artwork as a launchpad. Sketched with a geographer’s, geologist’s, naturalist’s, entomologist’s, anthropologist’s, and psychologist’s precision, Giono’s cascading descriptions are far more than a commentary on photographs or lithographs; they teem with relational tensions. He stages the manifold relationships between nature, animals, and humans as décor for the main characters. This technique could be called miniplay-staging, telling cascading stories in the fashion of the farmers, or structuring en abîme stories. The main point is the emphasis on nonanthropocentric relationships. Henri Peyre, in his 1969 review of Ennemonde et autres caractères, calls Giono’s view of nature pantheistic.[13]

Indeed, Giono’s nature is very different from the tame, subdued nature that was the norm in classical French poetry and literature. Edmund White calls it “raw nature”—something that he considers quite exceptional for a French writer.[14] But there is more than raw nature. Giono saw the world as native peoples do: nature is the one omnipotent, omnipresent, commanding feature of planet Earth, which animals and humans must abide. His rapport with nature, animals, and humans is in fact akin to that described by the renowned botanist and Potawatomi Nation member Robin Wall Kimmerer and the Native scholar Greg Cajete, according to whom it is not enough to just know a thing; we must understand it with mind, body, emotion, and spirit.[15] Thus seen, Giono’s world is in constant motion and tension. This picaresque and nonlinear understanding of nature indicates an important profession of identity by Giono.

Giono’s nature, animal world, and human society are incredibly rich and diversified.

Giono’s nature, animal world, and human society are incredibly rich and diversified. The landscapes of Camargue and the High Country feature not just topography but also climate, vegetation, rivers, seasons, days, weather, and smells as well as their interaction and impact. This complex microworld is placed in a dramatic tension with the macroworld of its broad geographic, even cosmic environment. Animal life includes feral and domestic animals as well as birds and insects, caught in a series of life-and-death dramas among themselves, nature, and humans. Humans are presented within the full context of their history, traditions, and culture, then in family and community relationships, and finally working with or against animals and submitting themselves to the laws of nature in what Balzac so aptly named the human comedy. The main characters are the apex of this complex structure.

Nature, Omnipresent

Both “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays” wax lyrical about nature. This is where Giono commits his first transgression from the “commentary” genre. His lengthy descriptions could easily become monotonous, but they contain plenty of drama and work as poetic metaphors. In the microdescriptions, Giono’s paean to the earth shows nature’s ritualistic, seasonal dominion over animals and humans: the murderous summer power of wild bees whose infinitely small presence is enough to challenge “the Greek God Zeus, the God of Abraham, and the God of Cromwell”; summers so hot that the air “becomes edible”; the slaughtering of pigs in the fall; and the birth of babies in September (out-of-wedlock babies in April). These microdescriptions are framed by macrodescriptions, stunning 360-degree panoramic vistas at sunrise. Dawn, the brief moment when Giono felt that all beings commune in the rising light,[16] relates the minuscule centers of Camargue and the High Country to its multicontinental surroundings. In “Camargue”:

The red of the sun is still in Piedmont when the broadest dawn imaginable is quivering here; night has not yet left the alleyways of Arles when a snowy light, multiplied by long reaches of water and sand, lays its gleamings on the empty expanses. The sea itself is still dark. By Miramas and Salon, and around the Berre lagoon . . . the dawn is still blue. . . . In Avignon the swallows are barely poking their bills out of their nests. . . . While the sun scales the Alps to the east, a brief moment of life takes hold in the Camargue. Night . . . flees toward the Cévennes; the African day that enflames the blood has not yet arrived. . . . At this time, as the sun is still inching its way up the eastern slopes of the Alps, all that crawls, all that leaps, makes the most of dawn. (II.138–42)

A similar description in “Le Haut Pays” affirms Giono’s own broad geographic roots:

Because God made enemies, he made this landscape, they say. That which destroys the hearts of humans is never terrible but, on the contrary, gladly tolerates calm and beauty. From Mount Viso, which is to say from Italy, all the way to Gerbier de Joncs and even, beyond that, to the dark bluffs of the Margeride, which is to say as far as Auvergne; and from Mont Blanc, which can be seen from far up in the North like a hazy looking glass, as far as Mount Sainte-Victoire, which sails due south in full rigging, and even, via the gap that separates Sainte-Victoire from Mount Apollon, all the way to the sea, whose lovely foaming roundness can be seen – these are the two diameters. Around the circumference of the circle, moving from the east and passing via the south: first, the High Alps of the Briançon region – Pelvoux with its snow and its Écrins, then Queyras and Viso – before which rise the Alps around Gap, the Dauphiné d’Orcières, then, a little farther forward, the Alps of Digne and of Barcelonette, which they call the Low Alps, contrary to all reality. (I.32–33)

This description continues for another page and concludes with a cosmic evocation of dawn:

. . . the sky strives to touch the low lands of the Crau, the Camargue, and the marshes of the Gulf of Lion. On this side, then, there’s no trace of a mountain, but often, at the moment you least expect it, in calm, fine weather, for instance, a strange color is seen to rise. It is a kind of black in which flecks of light seem to be quivering. At times you could imagine that the Andes or the Himalayas had loomed up with their shadows; at other moments it might be the sea rearing against a wall; in reality, it’s light devouring itself and, having done so, leaving in its place an abyss that is not even cosmic. This ferocity of light comes from the ceaseless shimmer of the choppy sea off Port-Saint-Louis-du-Rhône. The scrublands of Nîmes cannot find a way out of this inferno. (I.33–34)

If proof were needed that Giono is not just a folkloric Provençal writer, these descriptions would provide it. Giono’s Franco-Italian roots made him first and foremost a man of the Mediterranean world. “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays” gave him the opportunity to affirm this part of his identity. Nature has both a quasimystical dimension and concrete, everyday power, an inherent contrapuntal nature that embodies the writer’s own inner tensions.

Giono’s Franco-Italian roots made him first and foremost a man of the Mediterranean world.

Animal World

Tensions in the animal and human worlds introduce the quintessential twin questions of morality and mystery. The opening lines of “Camargue” warn us: “If I’ve spoken of theater, it’s because we’re part of an all-round dramaturgy, as in every sun-drenched land” (II.148).

The relationship among animal creatures is a fight to the death, an eros-thanatos dance between dangerous enemies, especially birds and snakes. These fights are set in a particular place, at a particular time of day, and in a particular season. These specifics help anchor the stories as quasireportage, especially in “Camargue” where the green whip snake:

. . . is easily three to four feet or more in length. It’s high-handed and enterprising; it climbs trees, plunders nests; it has a fierce, energetic character; it possesses a furious bite. The quickfire alone is capable of fighting back. leaping at its throat and driving it away. Others it swallows alive, naked and raw. It likes to feel its prey struggle and slowly die, even feel it scratch against its expandable gullet. It revels in the agony of others. (II.141)

The colonies of wild bees in the High Country fill pages with drama and danger:

Bees track tawny little reptile-like beasts – ferrets, stoats, weasels, martens – in hopes of coming by some freshly spilled blood or something rotten, from which, joyfully, they make their sugar. They stack their hundredweights of black sulfur-scented honey in the trunks of dead trees. It is so heavy that often the wood of these trees, dried by the sun and the winds, shatters and the honey spills, while the fury of millions of bees sets the sky ablaze. . . . They are not furious all the time. They’re never particularly proper, but you can get on fine with them so long as you don’t allow yourself to be overfamiliar and if you always cede territory to them. (I.38, 42)

Nature is not just savage; it is a place of fear peopled by monsters, mysterious, unseen mud creatures and predatory beasts. In the night of Camargue, love and death “emit the same fearful sound.” The absolute darkness of the night strikes fear in the inhabitants of the high country and leads them to barricade themselves in their homes. And the sky “is the eye of the fish” that rubs its scales against galaxies. Sheeps’ eyes drive shepherds to madness. The land is disquieting, and the sun is the black sun of Greek tragedy.

Humans

Giono’s descriptions of human life introduce a more familiar suspense. Even though the human social context is a bit less developed in “Camargue” than in “Le Haut Pays,” both regions are ancestral places of solitude and silence, austerity and tradition, sparsely inhabited by individuals whose world is shaped by nature, animals, and climate, and fortified by its own laws, economic networks, and culture. Giono knew Camargue from several of his trips and lived in the High Country for years. He had met some of the famed local cowherds, and he knew the High Country peasants from his years as a bank employee selling bonds and loans in the Manosque region. These are real people whom we might still meet today, even if their numbers are dwindling. Giono exaggerates some of their idiosyncrasies for dramatic or comic effect, such as the Huguenots’ strict and even hateful fundamentalism, or the incessant gossip that entertained bored countryside and small-town residents.

He also reveals tacit societal and gender dynamics that prevail underneath the veneer of patriarchy, such as clan dynamics, husband-wife relationships, or unconventional gender roles. This premodern world is so bare and poor that it leaves no place for the heart; it is one in which man has to sin to stay alive. It is an antique universe situated at the edge of the world, where poverty is so extreme that “no one destroys anything, the good and the bad, because they know that whatever it is, one fine day they might have need of it” (I.57). Love, a central theme in “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays,” is portrayed in a great variety of forms, from conjugal sex to prostitution, unconditional physical passion, or Platonic devotion. In “Camargue,” quick encounters between solitary men and prostitutes qualify as love only when a child is conceived; parental love takes center stage in single-father family units. In “Le Haut Pays,” the twin stories of platonic devotion, that of Camille and Titus, and of Ennemonde’s daughter Rachel and Siméon, come closest to true love.

Giono breaks open this ritualistic universe through external realities that allow him to pit evil against innocence and moral absolutes against moral ambivalence.

Giono again transgresses the “commentary” or ekphrastic genre by creating quasinovelistic universes in “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays.” These are closed universes with predictable dénouements; every group or individual has a part to play, as in a detective story. Thus pure hatred, in addition to building suspense, has a sure outcome and brings the highest satisfaction to those who practice it. For good measure, Giono breaks open this ritualistic universe through external realities that allow him to pit evil against innocence and moral absolutes against moral ambivalence. These external realities are represented by war, migrants, and civilization.[17] War is evoked as far back as nineteenth-century Italian independence struggles in “Camargue.” In “Le Haut Pays,” it is portrayed through daring episodes of resistance in World War II. As for migrants, an itinerant Gypsy basket weaver and his caravan appear and disappear in “Camargue,” leaving behind a child. In “Le Haut Pays,” the valley’s semivagrant homeless are in search of free food, and Clef des Coeurs, an accessory to Ennemonde, is a mercenary soldier turned itinerant wrestler. Giono’s migrants are survivalists who obey but their own fancy and live in harmony with nature. His resisters and vagrants represent the agony and ecstasy of freedom. Both are also part of Giono’s heritage and complete his “profession of identity.”

Modernity grafts its alien, “civilizing” force and intrudes on the world of flatland peoples and mountaineers like an anachronism. Ancestral communities are forced to adapt or resist. In “Le Haut Pays,” the coming of civilization takes the form of education and professional mobility: several of Ennemonde’s children move to the city and move up the social ladder. In “Camargue,” civilization equals urban sprawl and tourism. The asphalt paver is the enabler; this huge machine opens the countryside to automobiles and tourism like a dragoon. This brings to mind the role of the railroad in pre–World War I Austria-Hungary in the epic descriptions of Józef Wittlin: not only did it open central Europe to war in 1914, but it changed the ancestral way of life of the region’s ethnic minorities.[18]

The Last of the Mohicans?

Who are Giono’s heroes, the crowning pieces of his two stories? In biblical fashion, they are unexpected characters. They are strong, larger than nature, driven, and free. In “Camargue,” Louis, the last descendant of the cowherds, is part of a proud lineage; in “Le Haut Pays,” Ennemonde reigns supreme. Both are acknowledged as local aristocrats, even mythical figures, by their own communities. Even though they tower over others, their independence makes them innocently evil, and their situation as the last survivors of an ancestral world puts them in a fragile position. After a brush with the law and a stint in prison, Louis, the champion of the “cattle runs,” returns to a Camargue “no longer used for anything but scenery” where the old way of life is dying. Ennemonde defies conventional morality. Her indomitable “will to power” leads her to murder her husband in a perfect crime and to brush aside anyone who is in the way of her happiness.[19] She becomes the head of the household, a traditionally male role, by first appropriating her husband’s gun, then controlling the household finances and the farm’s business, and eventually becoming the most powerful businesswoman around. She hungers for life, feeds on the rich textures and fragrances of the air, and intensely enjoys the pleasures of the flesh.[20] She is a respected leader and a good person who is attended to with devotion by her own children when the infirmities of age reduce her to a wheelchair. Her beauty is of the most unusual kind:

As for her body, thanks to multiple pregnancies, it had come to resemble the bodies of the women of the High Country: it bore only the most distant relation to the human form. Her face was agreeable, despite the loss of all her teeth; her lips were full enough to remain in bloom. She had an attractive fresh, pink complexion; her brown eyes were extremely pure, without wrinkles or dark shadows, and were lined with long curving lashes. . . . She weighed over two hundred eighty pounds, but she moved with amazing agility. Men joked about the size of her thighs, without ever having seen them, of course. Despite her weight and her large limbs, she was easily capable of covering twelve miles on foot in five hours, on difficult paths. She had milk-white skin, having always protected it from the sun under a hat, long sleeves, and high collars, like all men and women who know what the sun really is. She wasn’t a woman who could be quickly explained. . . . There was all this monstrousness . . . and the look in those lovely eyes. That gaze led them to be cautious: not because it was hostile, but quite the opposite. (I.61–62)

Ennemonde is reimagined and metaphoric, like the characters of Faulkner’s South.[21] Other female characters show that Giono, while not a naturalist writer, paid close attention to the oft-invisible real lives of real people. He revealed the feminine in men and the masculine in women. He described women who spurn their bras, ignore fashion, and defy the objectification of female beauty. Of Myriam, the daughter of a Camargue cowherd and herself a cowherd, who pays forty francs to be impregnated by a stranger, he writes: “She had in abundance all that which makes men: a rough life and broad horizons, silence and natural laws, desire and solitude” (II.163). In this, Giono was decades ahead of his time; his characters resonate in all their diversity today perhaps even more than at the time of their writing.

Giono as Narrator

In these two carefully constructed stories, Giono crafts a new position as narrator. Heeding the ekphrastic genre, he positions himself as a witness and a memory-keeper. As witness, he appears to deliver true stories that occurred during his lifetime, specifically from the 1930s to the mid-1960s. He even becomes a participant by helping Titus take care of his beloved Camille in “Le Haut Pays.” Describing himself as a stranger from Manosque, and calling himself “naïve,” increases his credibility. And yet his deadpan humor warns the reader not to take him at his word. His matter-of-fact statements, far from innocuous, transgress the “commentary” genre. As stressed by Jacques Mény, Giono’s writing consisted in “rerouting things from their ordinary meaning.” Through this veritable tour de force, Giono places himself in the ambivalent position of faithful witness and transgressor of narrative conventions—another profession of identity.

A voracious and passionate reader, Giono loved to sprinkle his texts with colorful or humorous literary references, and in both stories we have a condensed version of his erudition. Defying the stereotype of a strictly Provençal, folkloric, local writer, Giono reveals his entire cultural universe with great abandon and relish. Deeply steeped in Greek and Roman antiquity during his youth, he was also familiar with Shakespeare as well as the nineteenth-century world of Victor Hugo, Stendhal, Rimbaud, and Flaubert. In “Camargue” and “Le Haut Pays,” he introduces cultural metaphors such as “Mahomet’s paradise,” fictitious shepherds, “the Dianas of Montemayor, the Faithful Shepherds, Astrées and Marie-Antoinettes,” and even Italian playwright and patriot Sylvio Pellico. A veteran of World War I, he understands military culture and uses technical terms such as automatic ejector shotguns, or boutons d’Alep, a skin disease common in the Middle East that he may have encountered while serving in the army. In “Camargue,” grasshoppers have the head of the medieval French king Philippe-Augustus, Hamlet could find his father’s ghost at noon in the Camargue, and “this very devoutly Catholic region” emulates Auvergne, Brittany, and Poland. Dante and Buffalo Bill are mentioned in one breath with Assyrian reliefs. Intellectual fashions are not spared the Giono treatment: in the High Country a gun is of more use than the philosophy of Monsieur Sartre, and in watery Camargue Monsieur Eiffel is easily dethroned by Monsieur Wave. Besides, there is an almost Ian Flemingesque quality to Giono’s exoticism, and an almost Rooseveltian quality to his enumerations of places and animals. Having traveled to Italy and Spain, he likens the “sugar cube” of Camargue houses to the earthen dwellings in Guadalquivir, Odiel, or Río Tinto near Seville. From his impressive library he draws knowledge of migratory species when describing birds who settle in Camargue from the distant Lena River, Amu Darya, Euphrates, Silk Road, Kerguelen Islands, Newfoundland, Puenta Arenas, and Sahel. And he cites the Magellanic grouse, the Beagle Channel, the Eskimo curlew, and American marsh birds along with the local birds of Camargue. Together, these literary, cultural, and geographic citations represent another profession of identity.

Most importantly, albeit most discreetly, Giono managed to express his beliefs. He was an environmentalist before it was fashionable, an enemy of industrialism before the critics of neoliberalism, a pacifist in wartime, and a proponent of country life long before the “return to the countryside” movement; the mass tourism of the “thirty glorious years” filled him with despair. His two stories come with a warning: when humans are in imbalance with the earth, bad stuff happens. Giono locks poetry against evil to try to save the world, help man keep his natural place in it, and recapture the innocence of élan vital despite constant struggles, ubiquitous moral ambivalence, and inherent contradictions.

Giono was an environmentalist before it was fashionable, an enemy of industrialism before the critics of neoliberalism, and a pacifist in wartime.

Getting closure on painful events he experienced at the end of World War II was important to Giono. In “Camargue,” Louis felt like a film extra after his release from prison, a feeling Giono may have experienced after his release from prison in 1946. Accusations of collaborating with the enemy that landed him in prison were particularly painful, and he appears to have been working for quite some time on gaining closure. His Occupation Journal entries for the summer of 1944 mention that he was working on Deux Cavaliers, which featured Clef-des-coeurs. The American military successes, the increasingly frequent Allied bombings of the south of France, and rumors of his impending arrest as a collaborator forced him to interrupt the novel in order to be “writing this journal, my self-portrait.”[22]

Clef-des-coeurs remained important enough for Giono to make him a central character in “Le Haut Pays” and to mention it in his 1968 introduction to Ennemonde et autres caractères. Do not be quick to judge, Giono says; drifters such as Clef-des-coeurs and murderers such as Ennemonde are good people who perform valuable actions even if they play ambivalent roles. Both supply the maquisards with free food from their farm, while Ennemonde enriches herself by selling meat on the black market. Ex-légionnaire Clef-des-coeurs dies a hero of the resistance more for the love of adventure than by conviction; he is the reason Ennemonde kills her husband, and perhaps, as Henri Peyre contends, also the owner of a gold coins treasure that both eventually find and hide from the rightful heirs and from the French authorities. Perhaps the peace that Giono claims Ennemonde felt at the end of her life, and her listening for the rain, are the closure that Giono desired toward the end of his.

Back to the relationship between text and art, each of the stories’ intensive narrative strands imposes its universe upon the artwork, along with a sensual universe of smells, sounds, and images whose imaginary presence superimposes itself onto the images. What dominates in the artist’s books, text or image? Today, reading “Part I” and “Part II” in the reverse chronological order of their writing and without their visual support, do we feel the absolute presence of the world that Giono lived so deeply and wrote about so eloquently? Giono must have felt that his texts were developed enough to be read without their visual counterparts, since he sent them to Gallimard to be published on their own.

Giono’s Franco-American Adventure

If Giono’s life and novels have been passionately discussed, their Franco-American ties have remained relatively unnoticed. Ennemonde gives a unique opportunity to reaffirm these ties.

Giono’s meteoric rise as a writer in 1929 was due to an almost simultaneous publication in French and English of Colline, for which he received the Brentano Prize in 1929, and of Regain, for which he received the Northcliffe Prize in 1930. The French followed suit by naming him Chevalier de l’Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur in 1932 on account of his activities as homme de lettres, forgetting that Grasset had initially refused his first novel Naissance de l’Odyssée in 1925 because of its unusual literary structure (Grasset published it in 1930). In the 1930s, Giono’s discovery of Moby-Dick was a turning point; he spent three years co-translating the novel and followed its publication with an exceptional biography of Melville.[23] After two prison sentences bookended the dark years of World War II and halted his publications, Giono experienced a spectacular literary rebirth. He was crowned by the Prix du Prince Pierre de Monaco for his life’s work in 1953 and inducted into the Académie Goncourt in 1954. The reputation that remained attached to him, however, was that of an easy and colorful méridional novelist, a reputation reinforced by the presentation of his works in the required Lagarde & Michard literature textbooks used by generations of high school students. Yet, during this time, one of his favorite American poets was Walt Whitman. Giono also began reading Hemingway, Dos Passos, Faulkner, and Steinbeck. Thus began his Faulknerian period, according to Emmanuelle Lambert.[24] And his 1951 novel Les Grands chemins preceded Jack Kerouac’s On the Road by six years, and likely influenced it.[25]

With so many ties to American culture, it was fitting that the current rebirth of Giono be a Franco-American venture. During the past ten years, several of his works have been retranslated or translated for the first time, thanks to the active collaboration between the president of the Association of the Friends of Jean Giono, Jacques Mény, and noted American novelist and essayist Edmund White. Two presses, New York Review Books and Archipelago Books, have taken the lead in this effort. Since 2016, NYRB published four works: The Hill, Melville, A King Alone, and Open Road. Of these, the three latter titles were first translations. A King Alone was translated by Alyson Waters, while the other three novels were translated by Paul Eprile. Bill Johnston’s Ennemonde adds to the Archipelago Books Giono series that includes The Serpent of Stars (2004) and Occupation Journal (2020), both translated by Joy Gladding. As previously noted, these are important publications since Giono’s lesser-known works reveal so much about the writer. On the French side, Jacques Mény maintains an excellent website, and Emmanuelle Lambert wrote a compelling biography, Giono, furioso, in 2019.[26] In 2020 the fiftieth anniversary of Giono’s death was celebrated with an exhibit at the MUCEM in Marseille. Back to the American side, the soon-to-be released Paradise Fragments, in the translation of Paul Aprile, awaits the reader at Archipelago Books.

References

Association Les Amis de Jean Giono, Manosque, France

Le Centre Jean Giono, Manosque, France

Pierre Citron, Giono, 1895–1970 (Seuil, 1990)

Emmanuelle Lambert, Giono, furioso (Stock, 2019), Prix Femina Essay 2019

Portes ouvertes Giono, 2020 Giono exhibition at MUCEM (Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée)

Works by Jean Giono in English

Hill of Destiny. Trans. Jacques Le Clercq. Brentano, 1929.

Harvest. Trans. Henri Fluchère & Geoffrey Myers. Viking, 1939.

Blue Boy (Jean le Bleu). 1948. Trans. Catherine A. Clarke. Viking, 1946 / Counterpoint, 2000.

Joy of Man’s Desiring (Que ma joie demeure). Trans. Catherine A. Clarke. Viking, 1940 / North Point, 1980.

The Man Who Planted Trees. Trans. Peter Doyle. n.p., 1953.

The Malediction. Trans. Peter de Mendelssohn. Museum Press, 1955.

Ennemonde. Trans. David Le Vay. Peter Owen, 1970.

The Horseman on the Roof. Trans. Jonathan Griffin. Hill & Wang, 1982.

Second Harvest. Reissue of Harvest. Harvill, 1999.

An Italian Journey. Trans. John Cumming. Marlboro Press, 1999.

To the Slaughterhouse. Trans. Norman Glass. Peter Owen, 2003.

The Serpent of Stars. Trans. Joy Gladding. Archipelago, 2004.

Angelo. Trans. Tom Geddes. Harvill Press, 2009.

Hill. Trans. Paul Eprile. NYRB, 2017.

Melville – A Novel. Trans. Paul Eprile. NYRB, 2017.

A King Alone. Trans. Alyson Waters. NYRB, 2019.

Occupation Journal. Trans. Joy Gladding. Archipelago, 2020.

The Open Road. Trans. Paul Eprile. NYRB, 2021.

Ennemonde. Trans. Bill Johnston. Archipelago, 2021.

Paradise Fragments. Trans. Paul Eprile. NYRB, forthcoming.

University of Tennessee at Martin