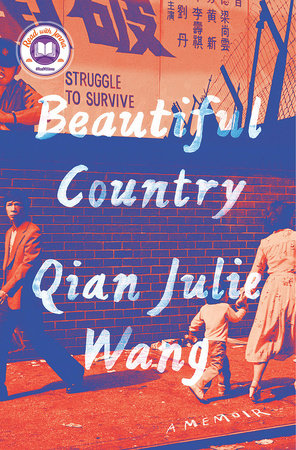

Qian Julie Wang’s debut memoir Beautiful Country is a compelling and intimate portrait of an undocumented childhood. Much like Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows In Brooklyn and Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, we are carried into the heart and mind of a child: this time, a young, undocumented girl in 1990s New York City who shows us an America that is not quite as it imagines itself to be. For little Qian Qian and her parents, each day is a battle for survival from fears and threats both internal and external, real and imagined.

With clarity and honest intimacy, Wang’s writing allows us to experience her childhood, taking us to the warm, familial, but constricted confines of her early years in North China, where she was born. We meet her father and mother, two struggling academics longing to raise their young daughter in a place like America, which they imagine to be a place of opportunity, streets paved in gold. With seven-year-old Qian, we discover the cold and hungry realities of being hei, the Chinese term for being undocumented, living fearfully in the shadows of invisibility and poverty. We sit with her and her mother in a Manhattan sweatshop, where little Qian snips threads from clothing her mother has sewn; we smell the stench of rotting fish as we enter a wet and freezing sushi-processing basement, where they sort through fish by hand; we feel the cold squelch of dirty water in Qian’s too-big boots. The fear in her stomach as she navigates the terrifying new world of New York City: constantly afraid of arrest and deportation, she dodges police officers and city workers bearing free food that her empty belly yearns for.

Reading Beautiful Country as a former undocumented immigrant, I cried and laughed alongside the familiarly deep, endless valleys and small, triumphant peaks of Wang’s years of fear and hiding in New York. In a wide-ranging conversation over Zoom, Qian Julie and I talked about the dangers and blessings of imagination while growing up undocumented, and the emerging canon of undocumented immigrant literatures.

Jill Damatac: In your book, you often contrast how the American Dream—or what I like to call the American Imagination—actually compares to reality, and that there’s that dissonance: when you were a little girl in China, you heard from family members that America was this land with gold-paved streets. And then you get to America. And as a hungry child, all you can think about is all of the food you ate till you were full in China. But actually, in reality, neither of those things are quite true. Can you talk to me about how the shock of that contrast—what you imagined versus what was real—shaped you into the person you are now, and how it’s shaped your parents, too?

Qian Julie Wang: Before we left, there were two different Americas painted for me, one paved with gold—and I remember hearing that and thinking, does everyone wear, like, shades and sunglasses everywhere? Because that’s going to be really bright!–and then there’s this other image of everyone just starving and lining the streets, begging for money and fighting over food. And they were, to my mind, equally possible worlds.

But because what we had been told to expect on both ends was very different from what we faced, and because my parents changed almost overnight, I could not trust anything. I was like, nothing anybody told me to expect is actually happening. I can’t trust what people tell me. I just have to be in control at all times. Take all the cues for myself and just be ready to act, and act perfectly at all instances, because I could not afford mistakes

[My parents] know what I was like before we moved. And so often now, my father tells me to relax. My mom says I’ve faced too much as a child, so now I don’t know how not to work. And it’s true. I don’t know when to stop. I can’t stop. In many ways, even though I’ve slowed down a little bit, it’s very hard for me. And she so wants that child back or wants to preserve that childhood for a bit longer. And that guilt follows her: who would I be today, if we had stayed in China longer, or forever? There’s no telling, but I think that’s it. She carries it with her that maybe I could have lived an easier life if they had made the decision differently.

JD: One of the things that floored me the most was the contrast between how you saw your mom. At first, you saw your mom in China as this joyful, loving, warm, happy person. And in America, you saw her as this tired, ill, overworked, neglected wife and mother. And it turned out she had this huge plan underfoot this whole time. How did that reshape the way you saw her?

The two selves I had: one that had originally been in me and the other that had been forged in the need to survive.

QJW: I was shocked, because for all of our years in America, she had, to my mind, become my child, even though I didn’t, of course, consciously think it that way. But I was like, “My mother comes to me with questions. I make decisions for her––sometimes very bad decisions!––but I am the person in control. She is not in control. She is not capable of doing something like this.” And yet, here she is in a car outside my school with all of our stuff packed: “I found a way for us to become documented.” And I’m like, “What? We did not run this through me. But let’s just humor her, because she really needs my support, because she really thinks is going to work.”

And the next day, driving to Canada, I was like, “Oh, this is really complicated. We have documents. It’s a heist. She had a safe house. We got to the border and I expect to jump into my translating. That’s my job, to manage everything. Make sure my mother doesn’t say the wrong thing. And they’re just like, “Go sit over there” and I think, “What? No, I’m in charge. You talk to me. Don’t bully her. If you want to yell, yell at me.”

And for the first time, I remembered what it was like in China when my mother just told me what to do, I did it, and everything was good. You know, it was two battling selves. The two selves I had: one that had originally been in me and the other that had been forged in the need to survive. They were fighting with each other before coming to a stalemate of “Let’s just see what happens.”

But time and again, [my mom] kept showing up: she went and got a decently paying job. Almost immediately, she found a house. I’m like, “You didn’t even let me go visit the house with you, to make sure it’s inhabitable.” I was left out, no longer in any sort of control, but still worrying about things. And that worry has very much stayed with me to this day.

JD: Your book is going to be in the Library of Congress, if it’s not there already. You’re going to be in university and high school curriculums, and there will be kids growing up reading this book. Let’s talk about who you are now: you’ve grown into a love for this country, for America. Beautiful Country isn’t just a memoir of your undocumented childhood. There are people out there who take offense at your book, who see you as unpatriotic, and “You’re ungrateful, and you don’t love this country, and if you don’t like it, get out.”

But as lots of us know, patriotism takes many forms, and one of them is loving your country enough to want to make it better. To criticize it as a way of making it better. I think your book does exactly what it says on the tin: it is about a beautiful country whose beauty lies in the potential of its people. And in your eyes, America can be beautiful, but only if it faces its own faults first. As someone who has lived in great poverty and has since built a successful life for herself, could you tell me how you think Beautiful Country exposes the imagined exceptionalism of America?

QJW: I think my story, though singular in detail, shares the very common immigration journey of coming here with stars in our eyes and then seeing that this country––though built by slaves and immigrants––is not really for people of color or immigrants. It currently does not think about immigrants; its health care system and its educational system––the very basic, fundamental poles of our society––does not consider immigrants.

It’s very comparable how humans evolve and how countries evolve. Neither can grow until they face the stark truth. Until you can embrace everything about yourself, every mistake, every horrible thing you’ve done, every good thing you’ve done–”This is what I’ve done but it does not define me, it was what I did, but I can choose to do things differently”––until you have the safety to do that as a nation or as one person, you will not be able to make different choices, because you remain stuck replicating the subconscious patterns of your past.

For a long time, I was stuck re-creating the conditions that were handed to me, which was to not let anyone get too close, to manufacture a reality and a version of myself. America has done that for so long. It would like to believe itself to be something that does not yet exist. And as long as it pretends that it’s already there, it’s never actually going to get there, which is what all of us want. It’s going to take some really hard work to get there, but the starting point is just being honest and examining those cracks. Yes, America did this, this, and this poorly, but those things do not need to define what America is, presently or going forward. And so, I think that if our nation could think about things in that way, our political discourse, our social discourse would be so much more constructive and would bring us closer to that version of America that we all want. Why wouldn’t we all want to live in the country so many claim America to be?

JD: These ideas shaped the work that you’ve chosen to focus on as an attorney, and that philosophy has kind of infused itself in the book. How did you decide to do what you’re doing now as an attorney?

QJW: Well, it was really a mirror of that journey. I went into corporate and commercial litigation, because I wanted to pretend that I was someone different who didn’t have this background, and I wanted to pretend that our country was better than it was. Before I went into commercial litigation, I actually interned at Legal Aid, legal services and public interest organizations. And when I saw the reality of what people were still going through, people like me decades later, still dealing with the very same barriers, it hurt. It was hard to see, and it made me feel incredibly guilty and defensive. How dare I live in my house with my books and shoes and handbags when this was still happening?

It’s very comparable how humans evolve and how countries evolve. Neither can grow until they face the stark truth.

And so I did what a lot of Americans do, which is run away and pretend: “OK, so I’m going to be in this pretty world, this rich world where those things don’t happen. It’s not part of my day-to-day. I don’t need to think about it.” But that can only hold for so long, especially for someone with my background, because I couldn’t go outside without seeing an immigrant child sifting through the trash with her mother. I saw that on my way to work, and as long as our society is the way it is now, I’m always going to run into some reflection of my past life, and it makes me feel incredibly guilty and ashamed for having run away and refusing to be part of the solution. So in the process of writing and editing this book and putting it out into the world, I learned to embrace what I just talked about, which is that I really need to get comfortable and accept the fact that our country is just not there yet.

What guides me now is thinking about that day that I’m on my deathbed. I don’t want to have any regrets. And looking back, if I have spent my whole life running away from reality and just living in this constructed bubble of “Everything’s fine, I serve the rich people of our country and everything’s fine and dandy, and I’m doing very well and everyone else is doing well, there’s no inequality,” I will not be able to die in peace. And that’s in many ways my self-serving guidance. I feel a moral imperative to push for progress and make inroads whenever possible. And my book is very much about reaching the reachable. I’m aware that a lot of people who most need to read my book will never read it. They may burn it. They may ban it. But any step toward progress is a step closer to living in the country we all deserve.

JD: You’re building an imagined world into reality. How do you feel about being part of this emerging canon of undocumented memoirs? There’s been a nice buildup over the past decade or so of memoirs written by lots of different kinds of undocumented immigrants. And no one’s experience is similar to anyone else’s.

QJW: It’s beautiful! I mean, I would not have found the courage to do this without Jose (Antonio Vargas, author of Dear America) and Karla (Cornejo Villavicencio, author of The Undocumented Americans). Jose wrote that essay in the New York Times magazine in 2011 (“My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant”). I was a 2L at Yale Law School on a student visa, then. Very privileged. And yet when I saw his essay and an interview with him, I was like, “Oh my God, he’s so brave.” Just the thought of me sharing that––that I had been undocumented in the past––had me shaking. It was his present! He has made himself so vulnerable to political attacks, to deportation, to everything. And it was so inspiring for me that he could dare to do that. And that was when the seed really was planted in my head: “If he can do it, what are you complaining about? You should be able to put this out there.”

But I had a lot of inner work to do before I could get there, and then of course, Karla’s book came out and focused not just on Dreamers, but on blue collar workers––the frontline workers of our society who are just ignored. And seeing how many people out there are still so impacted by the limits of our immigration system just gave me that final kick to send my story out into the world.

JD: I think what we’ll probably see is there will be more and more of us [undocumented] authors over time. It’s an honor to be a part of it––I’m kind of in your shoes that it’s not something I have to worry about anymore, but I still feel like I have to somehow protect my parents because they’re still there. But at the same time, I know that if anything’s going to change, the book has to happen.

Do you have any advice for memoir writers of color? Karl Ove Knausgaard wrote My Struggle, six autobiographical novels about himself. In his 30s! For memoir writers of color, we face a different challenge, in that the way we represent ourselves in the world, we apologize, repress our feelings, we code switch a lot. And sometimes it’s hard to get past that, that code switching tendency when we’re writing our memoir. Any advice on how to represent yourself?

QJW: We really have to know who we are and stand firm in that, because if we don’t, the world will tell us what to be and what to do. And that is really dangerous. We have to be able to say to ourselves, “I experienced what I experienced, I felt what I felt. And I wrote what I wrote,” and have that be enough; not to justify, not to have to pivot. And as you say, to not code switch, to not to have to explain or apologize or say, “I’m grateful for everything. I’m thanking you for letting me be alive.” Finding that firmness, that foundation of self-determination, is so necessary for anyone going into this field, but particularly for a person of color, for those from marginalized communities, because you will just receive that much more hate and anger. You have to just know that you are doing this because it is important. We are defying systemic barriers that want to keep us silenced, that want to hide our stories. Being a writer of color is an act of defiance. It’s important to remember that. Remember why we came in, remember that we are enough, that we don’t need to apologize.