I’ve always had a thing for strangers. I’m that person who can’t mind my own business at an airport gate, who strikes up a conversation with whoever looks as famished for connection as I feel. I love the gaping sense of aperture you feel among people in transit—how safe it is to tell a cab driver things you’d never tell your sister, your mother, any recurring figure in your life.

I have my list of sacred strangers, fleeting characters whose words and gestures are firebranded into my memory: the Dominican cab driver who chased down the bus on which I’d mindlessly left my luggage; the little girl who lived upstairs from me in Havana, whose maturing voice marked the passage of time over the many years I returned to visit Castro’s Cuba; the South African woman who steered me away from a fool’s errand of a hike up the Cape Town foothills and brought me to her flat instead, for a soulful chat about how to craft a life on your own terms.

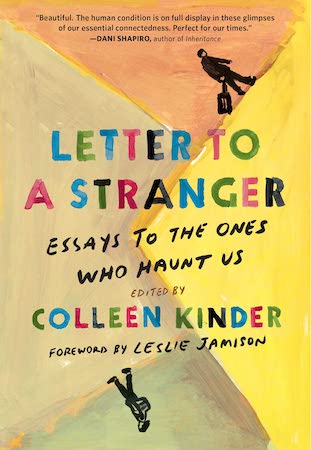

It was with these haunting strangers in mind that I schemed up the “Letter to a Stranger” column at the literary magazine Off Assignment, challenging fellow writers to pen a letter to a stranger they couldn’t shake. 65 of the most extraordinary responses to this writing prompt will be released in the anthology Letter to a Stranger: Essays to the Ones Who Haunt Us, a collection that spans every continent and delves into the intimate histories of a crew of exceptionally soulful and peripatetic writers. These stranger stories collectively upend assumptions about who counts as a pivotal voice or a major player in the narrative of our lives.

For this reading list, I asked some of the book’s contributors where in literature they’d witnessed the sorcery of strangers. They came back to me with recommendations for books featuring strangers who throw everything into a tizzy, who act as surrogates, who unearth beauty, who enable epic journeys, and more. This motley list reminds me of the simple truth that strangers embody possibility. They contain the full, wild multitude of our unspoken hopes for how our lives might change at any moment—who might hear us out, dare us to walk away, and who might beckon us into an entirely new storyline. Naturally, they make for great protagonists and supporting characters, even when lacking a name.—Colleen Kinder, editor of Letter to a Stranger: Essays to the Ones Who Haunt Us

The Ballad of Big Feeling by Ari Braverman

Structured as a series of vignettes revolving around a character known only as The Woman, The Ballad of Big Feeling captures the spontaneous intimacy that can arise between strangers on a local, daily level. In the opening scene, we see The Woman cradle a teenage girl having a seizure in the seat next to her at the cinema, the two of them striking “an inadvertent posture of care.” Later, she does the grocery shopping for an elderly neighbor, and has a conversation with a man lying on a mattress in the park about parakeets while walking her dog, through what, she realizes, is his bedroom.

Published during the socially distanced summer of 2020, the collisions of public and private in The Ballad of Big Feeling made me recall what it was like to live in a big city before the pandemic. While novels tend to focus on the plot of a select few, Braverman positions The Woman in relation to a wider cast, and her interactions with the people in her community are often more tender, surprising and revealing than those with her live-in lover or her family. Reading it reminded me that we are always part of a larger social constellation, and how crucial these “minor” interactions are to our experience of being alive.—Madelaine Lucas (“To the Boo Radley of My Childhood”)

The Beginners by Anne Serre

I read The Beginners the week after I moved to New York City, when I was staying in my friend Graham’s glass-walled apartment, suspended above traffic on Flatbush Avenue. It was August. I felt like I was on the precipice of starting my real life.

In the novel, Anna, who has lived happily for 20 years with Guillaume, meets a stranger named Thomas Lenz in town one day. This encounter upends her life. Like most things, the upheaval happens both gradually and suddenly. Serre paints a picture of Anna’s incredible yearning, set in motion by this stranger who reminds her unaccountably of Jude the Obscure.

“How strange it is to leave someone you love for someone you love,” Serre writes. “You cross a footbridge that has no name, that’s not named in any poem. No, nowhere is a name given to this bridge, and that is why Anna found it so difficult to cross.”

I too have found this bridge difficult to cross, and I too have had the furniture of my life unsettled by single encounters. I too have dropped, suddenly and gradually, out of a series of ordered lives. The Beginners felt like a balm, or even a talisman, as I sat reading and watching a storm blow in across the skyline, waiting for my life to start and wondering if it would stick.—Sophie Haigney (“To the Son of the Victim”)

The Address Book by Sophie Calle

After discovering a lost address book in the street, the writer and artist Sophie Calle reached out to the book’s listed contacts as an oblique means of getting to know the book’s owner. The resultant encounters and conversations she has with these contacts (those willing to meet with her, that is) are documented in The Address Book and help Calle to sketch a detailed, intimate, and transgressive portraiture of the book’s owner–who was wildly displeased when he learned about the project, which she had originally published as a serial in the newspaper Libération.

Of course, the investigative curiosity at the heart of this book displays in equally revealing detail Calle herself, whose obsession with strangers and boundaries drives much of her thinking and artistic work (see also: Suite Vénitienne and The Hotel). Ultimately, whether you view this work as invasive or exciting—or both, as I do—Calle’s desire to understand the subject of her chance encounter makes for an absolutely electrifying read.—Julie Lunde (“To My Steadfast Danish Soldier”)

WE by Yevgeny Zamyatin, translated by Bela Shayevich

At the heart of Russian author Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel WE is a sexy stranger named I-330. Sensuous and rebellious, I-330 is the antithesis of D-503, a spacecraft engineer and cipher for the state. She smokes and drinks, indulges in unsanctioned sex and is part of the rebellion. When D-503 first encounters her, he can’t bring himself to turn her into the police.

What happens next is his gradual awakening as I-330 introduces him to a lush world beyond the forbidden Green Wall. Zamyatin, a trained engineer himself, finished the book in 1921, combining his knowledge of math, science and literature, as well as his experiences living in a totalitarian state. Written in the form of a confession, the book electrifies through brief, exultant diary entries. The prose is immediate and full of symbolism, the syntax often odd, but delightful.

First published in English in 1924, WE influenced a cadre of early science fiction writers, including George Orwell and most likely Aldous Huxley. The manuscript was copied by hand and secreted reader to reader during Samizdat. Sadly, the author never saw his book in print in the Soviet Union, where he was imprisoned several times before emigrating to Paris and later dying in near obscurity. Today, WE continues to enjoy a wide readership and near cult-like admiration by writers and science fiction fans alike.—Rachel Swearingen (“To the Woman Who Found Me Crying Outside the Senate”)

The Door by Magda Szabo, translated by Len Rix

A young writer moves into a new home and takes on an old woman, Emerence, as her housekeeper. This is the premise of Magda Szabo’s The Door. You could hardly imagine a less exciting concept, but the glory here lies in this housekeeper. She is about as unlikeable a person as you can imagine: proud, rageful, secretive, controlling, at times, almost vindictive. In telling her story, however, Szabo does what we should all do more often, in writing and in life. She takes a stranger and finds what is beautiful in them. “A writer doesn’t necessarily need to die for the sake of truth,” Szabo said once. “But they must serve it at all costs. This is what all honorable writers do.”—Cutter Wood (“To the Seller of the Breadcrumbs”)

The Diver’s Clothes Lie Empty by Vendela Vida

A 33-year-old American woman arrives in Casablanca, where she is, almost immediately, robbed. The police say they’ve recovered her stolen bag, but when she goes to retrieve it, she realizes it’s not hers at all. Our protagonist—in a haze of jetlag, grief, and recklessness—takes the backpack anyways and, with it, its true owner’s identity: Sabine Alyse. This will be the first of five pseudonyms she adopts. We never learn her real name.

The Diver’s Clothes Lie Empty is a novel of proliferating doubles. (The protagonist, a twin, gets a job as a stand-in for a movie star, for whom she is later mistaken by paparazzi.) But places double, too: Police stations, buses, business hotels. We visit a neighborhood in Casablanca called California, that looks like Beverly Hills, and a bar called Rick’s Café, a recreation of the Rick’s Café in Casablanca, a film shot entirely in California. Morocco, our protagonist observes, often seems to be playing “Morocco” for the benefit of tourists like herself. It is also a novel populated entirely by strangers; the protagonist encounters nobody in Morocco who knows her from her life back home—with one harrowing exception. And they mistake her for somebody else.—Meg Charlton (“To the Woman With the Restraining Order”)

The Enchanted April by Elizabeth von Arnim

On a “miserable afternoon” at a women’s club in London, two lonely strangers—Mrs. Wilkins and Mrs. Arbuthnot—chance upon the same advertisement in The Times. It begins, mysteriously, “To Those who Appreciate Wistaria and Sunshine.” On impulse, they respond to the ad together, and two months later travel to a villa in San Salvatore, Italy, to spend—you guessed it—an enchanted April. Together Mrs. Wilkins and Mrs. Arbuthnot, along with newcomers Lady Caroline and Mrs. Fisher, get their proverbial groove back after the hardships of World War I, some mediocre marriages, and a dreary English winter.

Von Arnim relishes in providing lush sensory detail—strong coffee, bright sunshine, abundant flowers—and poking gentle fun at this unlikely quartet, whose personalities vary just as much as San Salvatore’s topography. And while there’s more than a little romance in this novel, the primary romance is between these characters and themselves, as well as their blooming friendships with one another. It’s an enchanting reminder that sometimes a change of scenery is in fact the best medicine, and that nourishing relationships can spring from the most unexpected circumstances.—Sally Franson (“To the Keeper of the Fawn”)

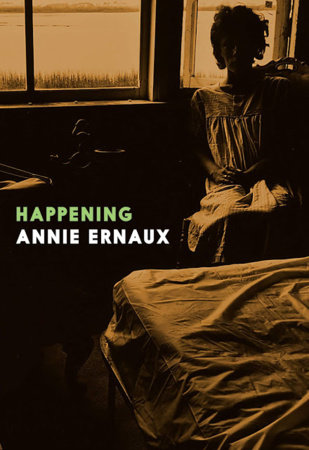

Happening by Annie Ernaux, translated by Tanya Leslie

Annie Ernaux’s memoir Happening is framed by the author returning, 35 years later, to the alley where she received an illegal abortion in France in the 1960s. We journey alongside Ernaux as she reinhabits her younger self and revisits the people and places woven deeply into that period of her life. In the early days of her unwanted pregnancy, Ernaux becomes a stranger to the world. Her body is foreign to her and everyone she encounters seems confined to a reality dominated by trivialities. She finds herself disclosing her pregnancy to a number of strangers and casual acquaintances, for reasons of practicality and for the purposes of speaking the truth of her experience into existence:

“I realize now: I had to reveal my condition, regardless of people’s beliefs or possible disapproval. Because I was so powerless, the act of telling them was crucial, its consequences immaterial: I simply needed to confront these people with the stark vision of reality.”

—Jenessa Abrams (“To the Gambler I Met on Jury Duty”)

The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle

H.P. Lovecraft isn’t exactly a name you want to invoke as an influence—Lovecraft was a deeply racist, xenophobic Providence man. And acclaimed author Victor LaValle has flipped the script on Lovecraft’s most notoriously racist story, “The Horror at Red Hook.” In 2016, LaValle published The Ballad of Black Tom, a novella that directly confronts Lovecraft’s brutal racism via its early-century Harlem setting and its Black protagonist named Tommy Tester—a street musician, hustler, and aspirant.

One day on the street, Tommy meets a stranger: the reclusive millionaire, Robert Suydam. Suydam convinces Tommy to come play at an exclusive party he’s hosting. Unbeknownst to Tommy, Suydam is trying to make Tommy a key participant in dark spells. With the Supreme Alphabet, Suydam wants to open a portal and summon The Sleeping King and The Great Old Ones (creations from the Lovecraft Mythos).

At the party, Suydam tells Tommy, “Some people know things about the universe that nobody ought to know, and can do things that nobody ought to be able to do.” It sounds like a horror-tinted warning about the dangers of curiosity, but more importantly it carries the deeper fire of an oppressor speaking to his oppressed: “We, the tyrants, know things you shouldn’t ever know. So don’t even go trying to learn them.” Suydam quickly becomes enslaver and Tommy becomes the trapped man trying to escape Suydam’s cosmic enslavement. Later on, because of his connections to Suydam’s portal attempts, Tommy is killed in a hail of 57 rounds, all shot by police officers.

As many know, it’s through fantastical stories that we better perceive our own realities. In The Ballad of Black Tom, LaValle widens that fantastic aperture to the point that early Harlem could be contemporary Minneapolis, MN, Louisville, KY, or Aurora, CO. And Tommy himself, swindled into believing a manipulative system that promises deliverance, isn’t simple allegory or reductive metaphor. LaValle treats his flawed protagonist with insightful compassion. At the same time, he attacks with bile and bite the systemic racism Tommy faces on the regular in Red Hook. Lovecraft would never approve of LaValle’s version of the story, and that’s exactly the point.—Alexander Lumans (“To My Arctic Vardøger”)

The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Mohsin Hamid

Mohsin Hamid is a magician: his books slim, structurally daring feats of literary devilry. The Reluctant Fundamentalist, his second novel, is my favorite for its audacity and its power. The book details an encounter between a Pakistani man named Changez and a burly American, who looks like he “bench presses regularly and maxes out well above 225,” unfolding as a conversation in a Lahore tea shop. Though monologue may be a more accurate descriptor, since we only ever hear Changez’s voice, the American’s presence is acknowledged cleverly through described reactions, or questions repeated back to the inquirer.

In the hands of a lesser writer, this self-conscious framework might ring false, too stagey for fiction. Yet Hamid manages to make the staginess natural to a story that is not really about two men meeting by chance in a tea house, but rather two countries—supposed allies—regarding each other with suspicion across a cultural chasm. Changez is a mesmerizing narrator who unfurls the story of his American miseducation with the flair of a court poet, by turns funny, coarse, infuriating and touching. The brilliant ending challenges our assumptions and biases as we are left to parse whether we have just witnessed a casual exchange between strangers or a set-up. —Keija Parssinen, “To the Source Who Kept Changing Costume”