When China fired a missile into one of its own weather satellites in a 2007 show of force, experts called the demo the beginning of a new antisatellite arms race. Fast forward to 2022, and a Chinese space tug is spotted towing a dead navigation satellite into a graveyard orbit above the geostationary belt.

“This is the type of space event that makes the hair on the back of people’s necks stand up,” said Brian Young, a former space control officer at the U.S. Air Force Space Command and now vice president of KBR’s military space business.

KBR, a Defense Department and NASA contractor with $6 billion in annual sales, paid $800 million in 2020 to acquire Centauri, a company focused on space sensors and satellite tracking. The acquisition gave KBR an entry into the business of “space domain awareness,” a military term for the capability to track objects in space and predict potential threats.

In January, KBR won a $39.5 million contract from the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) to analyze the effects of natural and manufactured threats to spacecraft, payloads and space services.

Young is based in Kihei, Hawaii, near the AFRL Maui Optical and Supercomputing Site better known as AMOS. KBR has several AFRL contracts to operate and maintain sensor sites and managed research projects on space domain awareness.

Another key customer is the U.S. Space Command’s National Space Defense Center (NSDC), a Colorado Springs-based group of 300 military and intelligence officials and private contractors who monitor space for hazards to U.S. and allied satellites.

Young, despite his many years as a U.S. Air Force space operator and military contractor, said he had never before seen China “grabbing a satellite and throwing it out into the graveyard” — as it did in January when a Shijian-21 spacecraft docked with a defunct Beidou-2 navigation satellite and towed it out of geostationary orbit.

Close approaches and proximity operations, however, are nothing new. “That stuff is happening all the time,” he said. “And we’re always monitoring those situations.”

What was also unusual about the Shijian-21 maneuver is that it was made public, Young noted. The events were detected by a commercial company, ExoAnalytic Solutions, which had been monitoring the Chinese spacecraft since it launched in October. Having these sensing capabilities in the private sector means more information can be revealed, whereas data collected and analyzed at the NSDC from government and commercial sources are typically classified.

KBR tracks space objects and activities as part of the NSDC’s Joint Commercial Operations cell. Companies that work in this cell are bound by more rigid reporting structures than purely commercial space domain awareness companies like ExoAnalytic Solutions or LeoLabs.

“Now we get to talk about that stuff because the commercial infrastructure is getting so good out there,” Young said.

THREAT WARNINGS

Space awareness is typically associated with collision avoidance. U.S. Space Command units and private contractors at Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, track satellites and debris to help prevent crashes in orbit, a capability known as conjunction assessment. They warn satellite operators worldwide when their spacecraft are at risk of colliding with another object.

The space domain awareness work done at the NSDC focuses entirely on military threats. “We call it indications and warnings,” said Young. The term is used in the intelligence world for activities to detect developments that could involve a threat to U.S. interests.

Despite an abundance of space domain data, not many people know what to do with it or how to turn it into useful information, he said.

KBR honed its expertise in indications and warnings in response to the growing U.S. military demand, Young said. Space Command has complex needs, for example, for intelligence and techniques to distinguish between naturally occurring events like orbital debris strikes versus intentional acts like maneuvering.

Differentiating between those two can be done with data analytics and algorithms, he said, but it’s not easy. “Space is big, and there’s stuff all over the place.”

“Sometimes you have to be at the right place at the right time with the sensors,” Young said. “And that’s why aggregating all of that data and being able to absorb all that data really helps in terms of trying to keep pace with the threat.”

The United States can’t stop China from moving its own satellites. “But what I certainly want to do is know when they’re moving around, and be able to forecast a little bit to know if I need to defend myself or protect myself,” Young said. “And so that is really the crux of it.”

For decades, space domain awareness was mainly about tracking orbital debris, updating the military space catalog and “making sure stuff didn’t hit each other,” he said. “And that’s just not good enough for today’s world.”

‘NO. 1 NEED’

The commander of U.S. Space Command, Gen. James Dickinson, recently called space domain awareness the command’s “No. 1 need.”

“We need to enhance our understanding of the congested and complex space operational environment, to include what is occurring and when, and the intent behind those engaged in such actions,” he March 8 at a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing.

China’s activities in space are worrisome, as many of its technological pursuits are aimed at countering the United States, Dickinson said. Space is at the center of Chinese military doctrine and strategy.

The goal of the Chinese military is to “blind and deafen” the enemy by crippling reconnaissance, communications, navigation and early warning satellites, said Dickinson. “Shijian-17 and Shijian-21, which are satellites with robotic arm technology, could be used in a future system for grappling and disabling other satellites.”

He noted that a Chinese spaceplane “could carry a payload designed to disable or capture a satellite while in orbit.”

Meanwhile, Russia’s “unsafe and irresponsible behavior in space” reinforces the need for adequate space domain awareness capabilities, said Dickinson, citing the November antisatellite missile strike that destroyed a defunct Russian spacecraft, dispersing nearly 1,500 pieces of trackable debris in low Earth orbit.

Dealing with debris congestion and antisatellite threats requires a “deep understanding of space objects and capabilities regardless of their national origin,” said Dickinson.

A lot of the work done to identify threats in space is enabled by artificial intelligence and machine learning, said Shelly Bruemmer, a KBR operations unit director based in Los Angeles. But sophisticated actions in space like what China did with the tug vehicle create new challenges for the military.

“The difficult part is determining intent,” she said. If Shijian-21 was cleaning up space debris, “is that the intent that they’re trying to show or was it another capability that they were trying to show? Sometimes you don’t necessarily know.”

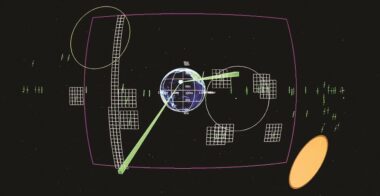

Part of KBR’s work for the NSDC is the development of software applications to help visualize space data and make it more accessible.

The U.S. Air Force, and now the Space Force, over the past five decades built a system of ground-based optical and radar space sensors known as the Space Surveillance Network. The most recent addition is a $341 million radar site to be developed by Northrop Grumman by 2025, the first of three projected new deep-space radars to be located around the world.

The military also relies on the Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP) satellites to monitor the geostationary orbit belt. The fifth and sixth satellites of the GSSAP constellation, also built by Northrop Grumman, were launched in January. These satellites were a state secret until the Air Force Space Command revealed their existence in 2014.

Over the past several years, AFRL and the Space Force have sought to boost space surveillance with data from commercial companies. They created what is known as the Unified Data Library, a cloud-based platform that hosts space situational awareness data from dozens of commercial, academic and government organizations, and provides a digital storefront for users.

Having such diverse sources of raw data is great for space domain awareness, said Bruemmer, “but you need people to sift through that data and analyze it and tell you what’s going on.”

U.S. HAS STRUGGLED TO RESPOND

Maj. Gen. Thomas James, commander of the Joint Task Force-Space Defense, a component of U.S. Space Command responsible for the protection of U.S. satellites, said that for years “we have watched China and Russia continue to build these capabilities” to counter the United States in space.

“And every time there was an event like the Chinese test in 2007, the United States struggled, in my opinion, to respond, and to determine what we are going to do to protect those satellites,” James said March 8 on a National Security Space Association webcast.

James said a more concerted effort to tackle antisatellite threats started during the Obama administration in reaction to Russian space activities. Alarms were set off after a Russian spacecraft in 2015 maneuvered around the geostationary belt, came close to French and Italian military communications satellites and parked itself between two Intelsat satellites in geosynchronous orbit for five months.

In the wake of that event, leaders from the Defense Department and the intelligence community “came together and said, ‘we’ve got to have a better way to get at this … we need to get all the right players together in the same place,’” James recalled.

That led to the establishment of the Joint Interagency Combined Space Operations Center (JICSpOC) at Schriever Air Force Base. That center evolved to what is now the NSDC.

Several U.S. intelligence agencies and all U.S. military services are represented on the NSDC floor, he said.

Space domain awareness has never been more essential given the sophistication of the threats, James said.

“We need to be able to see, sense and understand better and faster than the adversary does. If you can’t do that, you are not in a good position to gain superiority.”

Despite some innovative approaches — like using commercial sensors to supplement the military’s Space Surveillance Network — there are still “a lot of gaps,” said James.

Russia’s activities are always concerning but in the space domain “China is our pacing threat,” he said.

He described China’s Shijian-21 servicing vehicle as a dual-use system. Capturing a defunct satellite and removing it from a useful orbit is a legitimate debris-removal act, he said. “But there’s a concern that it could also be a threat.”

And establishing the difference between debris cleanup and a satellite grab is a major challenge, he added. “How you determine hostile intent is a very complicated process.”

It’s not just about identifying the technical capabilities of a system but also doing an intelligence assessment of what an adversary might be trying to accomplish.

Accurate intelligence about the space domain is a hard problem, James said. One of the challenges is that each sensor – the telescopes, radar sites and surveillance satellites – captures different portions of outer space so it’s not always possible to “maintain custody” of a specific object that might be of particular interest.

That requires analysts to piece together the data from all these different sources so they can identify where the object has been and where it might be headed.

This article originally appeared in the April 2022 issue of SpaceNews magazine.