I had a friend—we’ll call her Kinsley—who was as close to me as a sister for nearly 20 years. As we grew older, our values began to differ, but we both agreed that no difference was profound enough to break our friendship. Kinsley married a man she met on a religious website, sending me a text after one month of long-distance dating that read, “This is Christian [not his real name]! We have decided we are in love and getting married!” The following year she began expressing frustration over their inability to conceive naturally; she was ethically opposed to IVF. I was casually dating in New York and contemplating freezing my eggs.

Then, after 17 years of friendship, Kinsley abruptly ghosted me. The experience left me thinking about relationships that break under the strain of womanhood in all its conflicting forms. I have no doubt that for Kinsley and me, the looming pressures surrounding fertility (and our differing perspectives on motherhood, sex, and reproduction) accelerated our falling out. In her eyes, I was misguided (her word)—a black sheep among women. The last time I felt close to Kinsley was roughly seven years ago at a music festival. There was a torrential downpour and we huddled under a tarp, sharing poutine and drinking beer. When we were in line for poutine round two, we playfully debated the morality of birth control (insofar as that conversation can be playful). Even then, the chasm was widening.

For Maeve, the protagonist in my debut horror novel, Just Like Mother, there’s no fitting in. As a young girl raised in a matriarchal cult that reduces men to chattel for breeding, her misplaced affection for a male relative results in tragedy. As an adult, she cobbles together a flimsy existence that appears normal from the outside but conceals her profound loneliness and inability to connect. When her long-lost cousin—the one person who truly understood her in childhood—reappears in her life, Maeve is thrilled to let her back in, stubbornly ignoring every red flag in favor of the emotional intimacy she craves. Andrea offers Maeve everything she lacks: acceptance, stability, and belonging. But Andrea’s love comes with its own set of conditions; and when Maeve falls short of familial expectations for a second time, she faces brutal consequences.

The following is a list of books about characters like Maeve, who are unable to be the type of women their communities expect them to be.

Adèle by Leila Slimani

The Perfect Nanny put Leila Slimani on my radar, but Adèle cemented my devotion to her work. The titular character has, by all accounts, an enviable existence: one she is proud of and in theory, committed to. She has a successful career and a loving family. Some might even consider her life the feminine ideal. But Adèle finds herself plagued by overwhelming dissatisfaction; and because of it, she is emotionally isolated. Her efforts to correct her profound loneliness through illicit sexual only enable the downward spiral. Through her discomfiting descriptions of Adèle’s exploits, Slimani makes it clear that Adèle is a woman who desperately wants to want the life she has, but can’t.

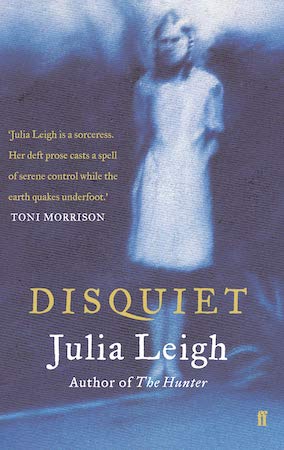

Disquiet by Julia Leigh

Olivia is reunited with her brother Marcus and his wife Sophie after she leaves her abusive marriage and brings her two children to the family chateau. But all is not well with Marcus and Sophie, who can’t bear to part with the corpse of their infant daughter. This gothic novella kept me riveted with its nuanced portrayal of dysfunctional family dynamics and motherhood. Anyone who has ever gone home for the holidays and experienced the gloomy push-pull of what remains unsaid will recognize their own in this unsettling story. Julia Leigh is skilled at emotional brinksmanship, sustaining nerve-shredding atmospheric tension through to the end.

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

Keiko, a woman working at a convenience store in Tokyo, best understands how to function “normally” within the framework of her job at Smile Mart, where social interactions can be learned by studying a manual. Keiko flourishes at the store and achieves a level of contentment she hasn’t experienced elsewhere; but as she approaches middle age, her lack of ambition and marital status (single, uncoupled) become an increasing affront to her meddling family and coworkers. Keiko contorts herself into a desperate emotional pretzel in an effort to appease her loved ones. The resulting decision is comically aligned with her personality—an unusual arrangement that makes her even more of an aberration, at least by the standards of people who care about such things.

The Aosawa Murders by Riku Onda

Hisako, the daughter of a local physician, is the only survivor of a birthday party turned foul when more than a dozen people die from cyanide poisoning. Hisako is blind and is unable to provide much to the police by way of details about the horrific event. When the main suspect commits suicide, the town is left with questions; and a decade later, all roads seem to lead to Hisako. The story unfolds through various characters’ testimonies. While the ending is somewhat inconclusive and the motives feel a tad thin, this is nevertheless an exciting mystery and fascinating character study. (And the cover is amazing.)

The Door by Magda Szabo

This novel left a profound impression on me when I first read it five or six years ago. Magda, an educated and privileged writer, develops a complicated and potentially co-dependent friendship with Emerence, her illiterate, cranky housekeeper. Emerence charmed me with her hard-won love, and the emotional restraint of this novel makes the eventual revelation more devastating.

Emerence’s house is closed to outsiders. She alone is allowed to enter. What lies behind her door? It’s difficult to discuss this character-driven plot without spoiling it; but this is a novel you’ll want to read twice, and Emerence is one of the more complex, interesting characters I’ve had the pleasure of reading.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

Yeong-hye enjoys a quiet, structured life with her husband until she refuses to eat meat, a consequence of her violent nightmares. The decision is an act of unacceptable rebellion, according to her husband and in-laws. What results is domestic horror: a perverse fight for control that becomes more and more extreme as Yeong-hye stubbornly asserts herself. To be honest, I read this one quite a while ago and remember the details as a fever dream, but I loved this uniquely grotesque take on feminine power and the violence that occurs when a woman fails to fall in line.

Chemistry by Weike Wang

In Chemistry, we meet another woman with a life that is by all accounts rewarding, yet fails to deliver happiness. The novel’s narrator is working toward her PhD in chemistry—a goal foisted on her by her parents—and her perfectly lovely boyfriend has proposed. But she’s mired in ambivalence about her career and relationship and struggles to untangle her own wants from the wants foisted on her. As the story develops, the narrator reveals aspects of her childhood that led to her present state of indecision. This is a moving, character-driven illustration of what happens when the presence of others looms so large that there’s no room left to develop your own identity.