The most elusive prize for poets of any kind, at any time or place, is endurance. It’s not something poets can specifically work toward or ever claim for themselves and, if achieved, it may not even be in their lifetimes. To capture that elusive quality of being a poet who endures is up to many factors, but ultimately falls upon the readers—that wider anonymous audience—and not from any conferred award or the luck of tapping into a specific historic cultural moment. It comes from the combined uniqueness and familiarity of the poems themselves and sometimes even from the bodies of work built from years of widely reading and writing.

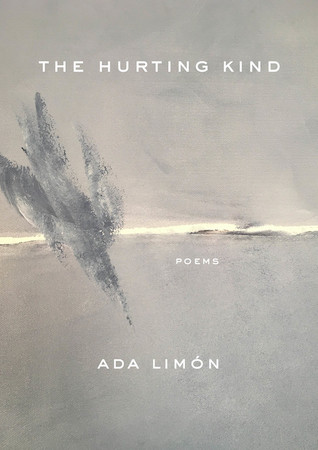

Therefore, using the term endure for a poem or poet is certainly not something to bestow lightly. It is, however, an accolade I feel no hesitancy in applying to Ada Limón. She is a poet of both studied and innate talent and with each poem, each carefully crafted collection, Limón has gifted us with an oceanic well of wisdom, intertwining our humanity with the natural world we live within. The Hurting Kind, her latest offering, is a powerful meditation on relationships with love, loss, family, friends, interlaced with an equal intimacy with the land, trees, plants, and animals. Anyone can see themselves in these poems but, more importantly, they can sense the lessons of our ancestors and the grief we must reckon with collectively, together, if our species will survive ourselves and continue to endure.

I had absolute pleasure of talking to Limón about her new book, fighting back against being forced into prescribed boxes, as well as learning about a forthcoming collection of essays on trees she’s currently working on.

Angela María Spring: The Hurting Kind, like much of your work, is a conversation; a conversation between poet and reader, between humanity and nature, conversation between the cyclical changing seasons both literally and metaphorically, a conversation about what we desire most and what we must learn to accept. What is the most important conversation you, the poet, want to have with us, the readers, in this particular book?

We are all part of a community, we’re all connected.

Ada Limón: We are all part of a community, we’re all connected. And sometimes we work so hard at trying to fit in somewhere to find our community, to figure out what it is that makes us connected. I think if this book is saying anything, it’s saying: you’re already connected. You already have all that you need. And it’s in everything that’s come before you and it’s in everything that’s going to come after. It’s the Earth and it’s the animals and it’s the plants and that is our community. I think so much of our lives are spent searching. I think if this book is saying anything, if it’s saying anything to me and saying anything to my readers, it’s that: we don’t need to look, it’s already there.

AS: I do love that the language of your poems is so conversational to really powerful effect, such as the line “In between my tasks, I find a dead fledgling,/maybe dove, maybe dunno to be honest” in “Not the Saddest Thing In the World,” because you stop and dwell in it. We don’t put things in our poetry without intention so you’re stopping the reader on purpose. But it also leads us to the ever-present question of “accessibility” that the poetry pundits cannot seem to shake. It’s a sort of trap, maybe even a gaslighting technique, to look down on narrative poetry, especially since so many Black and Brown poets have been narrative (with more BIPOC poets publishing, that has finally become obviously untrue).

How do you resist this gaslighting and politicizing of your own work and what advice can you give to younger poets who find themselves mired in this same muck of white, colonial perspectives forced upon them and their work?

AL: I think it’s really important right now. It’s important, always, but I do feel like one of the things that we have to be very wary of.

I was just having this discussion at Butler University in Indianapolis, which was that we really have to be careful about the commodification of pain and trauma within our work and what is required of us from outside of our community, and sometimes from within our community. I feel like we have to make sure that we’re giving ourselves permission to have the same type of freedom that any artist could have, an artist of any background. It’s really important to not just hang onto the joy, that’s important, and we need that for so many reasons, for survival, for resilience. But it’s also as a rebellion, you know, but I think that if by showing our whole self. What we’re doing is making an argument for our complete and beautiful humanity. When we fall into the trap of only talking about our trauma or only talking about our political situation because those are the poems that get attention or those are the poems that win prizes or those are poems that the white community really reacts favorably to, I think we have to be very concerned with not only whether or not we’re giving ourselves freedom as an artist to write whatever we want, but also whether or not we’re giving ourselves freedom as a human being to have all and hold and contain all of the spectrum of human emotion.

It’s a dangerous thing any time we fall into a trap of listening to what other people require of us—and again, that can be from inside or outside of our community—and I feel like every time I’ve been asked to fit into that mold, any mold, I find myself sort of all elbows, I want to push it and push against it. And that’s not to say that the work in exploring trauma and generational trauma is not really important. But I do think we need the other work also to balance us out; that work of joy, survival, that work of daily-ness. So there we’re saying, I exist in a day-to-day, momentary, casual being that moves through the world just like anyone else. I think that’s really essential to not just artists, but to anyone who’s trying to live in this world that wants us to only be our short biography, only our identity. What is our identity? I’m very curious as to why we always feel the need to limit our identity. I like my identity, my identity is a lot. It’s many, many, many things. It’s Latinx but it’s also Irish, it’s also a human being living on this planet during the Anthropocene at the height of a tipping point for our planet. All of these things are part of us, and I feel like any time we limit ourselves, we’re putting a cage on our soul and I think that if poetry wants to do anything, it’s to allow ourselves to be free.

AS: That’s the decolonial work. I’m always wanting to know how does everybody do it in their own way.

We have to be careful about the commodification of pain and trauma within our work and what is required of us from outside of our community, and sometimes from within our community.

AL: Part of that work is really for me. It’s like it’s saving me and I have to do it in order to feel like I’m honoring this world. And that is a big thing when we talk about what is required of us or expected of us or what kind of box people want us to fit in, I don’t think we realize how much we also have it in our head. I don’t think we realize how much we also have it in our head, that it’s not just like someone saying this or someone accepting a poem or not accepting a poem, but it’s deeply ingrained in our bodies, in our soul, in our hearts and our brains, and that’s the stuff you have to slough off. That’s the stuff that’s with you when you’re alone writing a poem. And that’s hard work.

AS: You wrote something in a social media post that I cannot get out of my head: that you were writing an essay about trees that went on and on you didn’t want it to end and I wondered if that was perhaps how trees communicate. I kind of laugh at myself because I think writers over 40 who live in a more nature-heavy environment and tend to write about the land, trees become more and more important. Do you think we need to begin to decipher the language of trees, if it’s even possible? Basically, tell me all your thoughts on trees because I honestly think each tree is a poem and we just need to listen and watch to see it unfold.

AL: I love that you think that; I think that, too. Sometimes I’ll look out and go, oh, I know I haven’t looked at and praised my hackberry in a while, I better go out there and give him some love. Or like when I was talking about that sense of community, my trees feel like my family, right? When I say mine, they’re not mine, I’m in their space, but I feel like it’s really important to not only like name, which I talk about naming, right, that importance of naming, but then there’s like the other part of it, which is, to not name, but just to feel. I really feel what it is to stand with a tree and I’ll tell you, I can be in my most chaotic, in my most suffering mind, and if I can be near a tree or sit near a tree or put my body near the bark of a tree, I am like, oh, right. I am so small and so unimportant. That kind of decentering of the I is so beautiful and really refreshing, in which we don’t have that very often, you know? We’re told we have a list of things to do, this is what you do. We’re also told, you’re unique and special and you have all these things and I’m always like, but not really! I’m not. We’re all in this. I’m not any better than this tree. In fact, I would argue that’s more important than me. Maybe it is an age thing, maybe it is a nature thing, but I do think it feels like what trees do for me is remind me first of all of that connection, that we’re connected, I feel connected to them and I hope they feel connected to me. But also there’s a there’s a lot of them in our life. They’ve been with us forever. If you start to think about like your first tree, it starts to unravel and you realize that, oh, this has been part of my community, and these are part of my teachers. This is part of where I have learned to say that this is part of why I’m an artist. It’s because of staring at trees and what the trees have offered back. It sounds maybe out there, but that’s truly what I believe.

AS: In your acknowledgments, you thank your stepfather for helping you think The Hurting Kind could really be a book, and I think about the collection structure in the poems, how they come together in a brilliant seamlessness, which considering what you said about you thinking of it as one long poem absolutely makes sense. I know that these past years have been full of so many personal challenges that we can barely even guess at, let alone glimpse. So I want to thank you for persevering to give us this beautiful collection and also like to know if there was some backstory of how the collection came to be.

AL: The poems were written over the last five years, so they’re not all written during the pandemic because The Carrying came out in 2018 and of course, it was probably at the press in 2017. So if you think about that, this has been at least four or five years’ worth of work. That said, one of the biggest hurdles that I had to overcome was I really wanted to put in so much that I had worked on and, here’s a thing, I’ve written way more than this in this book and they didn’t fit. A lot of them were projects like ekphrastic poetry I was asked to do for MoMA but it’s a poem for Frida Kahlo, one of my heroes, or a poem for Leonora Carrington, the Mexican surrealist. I wanted to write all these and include them but every time I looked at it, I [realized], this isn’t the collection for this.

Those poems will exist in a different collection but I had to really recognize that this work was doing that work of interconnectedness. It was a work about honoring the plants, animals and ancestors, and I felt like if I if I wasn’t true to that it would feel like, oh, now we’ve gotten to the fourth section where she’s put in things that she’s written, which is totally fine, and I love books that have disparate themes and are just a lot of poems, I love that, too. But I think this book, for me, felt like it really did need to be a long poem. It needed to be that sense of ongoingness, a little bit of the decentering of the self, the deep eye of watching. Then I also felt like the moment the seasons came to me and that it was seasons and not a narrative arc, I [knew], that’s it. That’s how this works, it’s not about “I have gone through this,” it’s that “this is happening,” and that was really important because it had to be also the sense of ongoingness that what is a cycle that continues without me being in it? It also what happens when you finish the book and return to the beginning because what comes after winter, but spring? So it’s like that sort of opening and then it was, oh, right, if this is about more than me, then let this cycle of the seasons become its engine. And once that happened then I knew the book was almost there.