Mom Has Her Boyfriend, I Have Her Cigarettes

Smokes Last by Morgan Talty

At the kitchen table, Frick fidgeted with a bag of pork rinds. Mom scrubbed dishes while the oiled pan on the stove got hot enough for her to lay down spoonfuls of batter in it. The sideboard was caked white. The house smelled like the empty sweet-corn can that sat upright next to the sink.

“Back west, when the Minnechaduza Creek froze over,” Frick said, sitting perpendicular to the table, “we used to go and wait for the white kids to try and cross. Once they made it halfway,” he raised his arms and looked down the barrel of an imaginary rifle, “—pop!—and we’d shoot. I guess our battles were for a different time.” He reached into the bag and pulled out a pork rind.

I got up from the table.

“Don’t come home blind,” Mom said, examining a glass cup and then placing it to dry. “And bring the mail in before you go, gwus. Your father said he finally sent some money up.”

Sure he did. The last money we’d seen from him was on my last birthday, when I turned fourteen.

Frick chewed a pork rind and then paused. “That’s how I lost most of my vision in my right eye. Rock wars, we called them.” He dug in the pork-rinds bag again, feeling for something other than rind dustings and crumbs.

“Well,” I said. “If I lose my vision I won’t come home.” Frick wiped his hands on his jeans, and Mom slammed a plate down in the sink. “Stop that!”

Frick and I looked at her.

“Wipe your hands on them one more time,” she said, pointing at him with a soapy finger. “I gave you a napkin. Use it.”

Since Paige had gone to rehab six weeks back, Mom didn’t have anyone to snap at, so that left Frick and me. I went for the door.

“Don’t forget the mail, David.”

I turned the cold doorknob and the November air nipped my fingers. Everywhere, bare tree branches reached at a gray sky. With the ground covered in leaves, it was harder to find good sticks for a battle. I walked down the road past all the same long rectangular homes, the only difference being color. I smelled ash and chalk—somewhere a fire burned. Crows cawed in the distance and the road came to an end. Through the high grass and into the woods, I set off along the riverbank. The river was moving fast, but the cold moved faster. Soon, all would be frozen again.

I trekked along the riverbank until I came to the fallen tree where JP and Tyson said they’d meet me. In rapid bursts a woodpecker drilled on a tree in the distance and the river carried the sound. I unzipped my jacket and reached in my hidden pocket and pulled out a Winston 100 and a red Bic. The cigarette sizzled in the flame.

Smoke clung to the cold air like it clung to my lungs. Exhale. The wind off the river was chilled. The crispy fallen leaves crackled behind me. I faced the sound. Tyson was wearing his bright orange jacket.

“You going hunting?” I asked.

He laughed. “It’s the only jacket I got.”

“Puff?”

He grabbed the cigarette and pulled off it. “Where’s JP?”

“Thought he’d come with you,” I said.

Tyson looked out at the water.

“What, you want to swim?” I asked.

He looked at me like I was stupid and then pointed with the cigarette to his feet. “I’m not getting my new shoes wet.”

“You know you’re going to ruin those shoes before today’s over.”

“Nah.” He blew smoke. “My mom will kill me.”

“Whatever you say.” I took the cigarette and turned back toward the river. “So when’s JP getting here?”

Tyson looked at me, startled, and then he laughed. “Oh yeah, he said head down to the spot and he’d meet us there.”

“So if I didn’t ask, then we’d be waiting here for no one?” I poked him in the chest. “I’m telling JP you forgot what he said. He’s going to go after you during battle.”

“He’s going to go after me no matter what.”

Tyson followed me into the deep woods, bending and twisting through tree limbs. “Well, now he’s going to go after you even harder.”

We had spots all over the Island. Dry spots. Wet spots. Lonely, unvisited spots. Where we were going had been someone else’s spot years ago: a rope swing hung from a high branch off a tree that had an old rotting tree house in it. Nothing grew within fifty feet of there.

When we arrived, JP was on the rope swing, one foot stuck in the knothole, the other dangling. The tree branch bent and creaked under his weight.

“I been waiting long enough,” JP said.

I pulled another cigarette from my pocket and lit it. “Tyson said you’re too heavy to be on that.”

“What?” JP struggled to free his foot from the knothole.

“No I didn’t,” Tyson said.

I said it again. “Tyson said you were too heavy to be on that.”

“Heavy? You wait, Tyson. I got a heavy fucking stick com ing your way.”

Tyson’s voice cracked. “I didn’t say that!”

“Don’t matter if you said it or not.” JP freed his foot. “What matters is it was said. And you’re done for.” We walked closer and JP met us. He then plunged two fingers into Tyson’s chest and laughed. “Just messing with you. Let me get a puff, David.”

I handed it to him. In between drags JP watched Tyson. JP kept shaking his head.

“What?” Tyson said.

JP ignored him and exhaled. “Here.” He passed the cigarette to me. JP walked away from us, and he glanced over his shoulder. “You best get running, Tyson. You got twenty seconds.” JP bent over and picked up the first stick.

I took one last rip on the Winston, handed crack-drag to Tyson, and ran, scanning the ground for ammunition.

Sometimes, we had twelve people play and sticks flew from every direction and people quickly got bored; sometimes— most of the time—it was us three playing, and those games lasted hours. Once, Tyson hid so well in the woods that JP and I gave up and left him. He thought the game was on for hours after we had quit.

There was only one rule in battle: submission meant game over for the person submitting. It was a generous rule, but JP never acknowledged it, especially when Tyson said he surrendered.

I picked up some small sticks, and I saw Tyson was following me. “Get the fuck away from me,” I told him, and I ran as fast as I could. When I looked back, there was only the gentle rocking of the woods behind me.

I had run toward the riverbank and was trapped against it. While I stopped to catch my breath I searched the ground for better sticks and found a few long and short ones. I walked cautiously, avoiding any twigs that might snap or dried leaves that might crunch. Progress was slow; it seemed as though hours had passed before I made it fifty feet. Crows cawed loudly and the river smelled damp. Off in the distance, a treetop rustled and birds flapped their wings and flew away. Someone was walking.

A row of pine trees blocked the view, but I approached slowly and crouched down behind them. Smells of pine and sap filled my nose. A branch snapped.

He was there, bright orange appearing from behind trees and getting closer. I ducked down and watched with my ears. If Tyson’s here, I thought, JP isn’t far behind.

I stood, cocked back a thick stick, squinted my eyes, and barreled through the pine tree branches, needles pricking at my face.

SMACK. I crashed into a body and fell over.

“Jesus Christ!” JP said.

I lay on the ground looking up at him. He stared back at me, a look of both confusion and wonder at how he hadn’t heard me. Then he lowered his brown brows, battle-mode.

He poked my chest with a long stick. “You’re done for,” he said. As he pulled the stick back to swing at me, I was about ready to surrender when something smashed into JP’s back.

JP jumped and swung around. “You little shit,” he said. “You’re dead!”

Tyson’s laugh filled the air while JP chased him. I rolled over and stood, and then I snatched up my sticks and ran after them. Tyson was leading JP back toward the spot with the rope swing.

JP only slowed down enough to wing a stick at Tyson, who looked like an orange peel running through the woods. When they broke through brush and came to a clearing, Tyson turned, and in one last effort to save himself from JP’s wrath, flung a stick hard at him.

JP dodged it.

I dropped to my knees and grabbed my eye.

“I submit!” Tyson screamed.

One final loud crack hit my ears and Tyson wailed.

“I guess I win,” JP said, laughing.

“I submitted!” Tyson said.

I opened my eye and I could see, but blood ran down my face and covered my hands. Tyson lay on the ground rubbing his back. JP hurried over to me.

“You all right?” he said.

“Where am I cut?”

JP bent down and looked. “Between your eye and your nose. Man, that’s a deep gash. Nice battle wound.”

“It need stitches?”

“No, let’s go to Tyson’s and clean it up and get lunch.”

“Fuck you, you can’t have lunch.” Tyson stood and rubbed his back.

“I can have whatever I want. I’m the winner.” JP raised his fist.

“Fucking hell,” Tyson said. “Look at my shoes.”

Thick mud covered his new sneakers.

Tyson stood in front of the bathroom mirror lifting his shirt as he examined his lower back. He held his muddy shoe in one hand.

“Would you move?” I said. “Your back’s fine.”

“It hurts. And I have to clean my shoe.”

“There’s no scar and you can clean your shoe after. Move so I can clean this blood.”

“Where’s your mayonnaise?” JP yelled from the kitchen.

Tyson set his shoe in the tub and went to the kitchen.

I looked at my face. Pale skin. Dark bags under my eyes. A thin, tear-like layer of blood streaked down my face. The blood from the gash between my eye and nose had hardened like dried red paint. I turned on the sink. Blood stained my hands and seemed to belong there. I scrubbed my hands hard with a bar of soap and then scrubbed the line of blood off my face. The area around the cut was beginning to bruise.

With a cloth, I dabbed the gash, gently scraping away small bits of crusted blood. It bled again and was watery. I pressed a Q-tip soaked in peroxide against the wound and winced. I dried the area and put Neosporin on it. Behind the mirror I found a box of assorted Band-Aids and stuck a medium-small one vertically between my eye and nose.

Tyson’s parents were working so I lit a cigarette and walked into the living room. I plopped down on the couch.

“Nice Band-Aid,” JP said. “It matches your vagina.”

I laughed. “Shut up.”

JP finished his sandwich. “You going to make one?”

“I’m not hungry.” I flicked my cigarette.

“I call David’s sandwich.” JP went back to the kitchen.

Tyson stood. “Don’t, you’ve used most of the bologna.”

“Relax, you have an unopened package of it in the fridge drawer.”

Tyson could do nothing but watch while JP piled on the fixings.

“Sorry about your face, David,” Tyson said.

“No worries.” I passed him the cigarette.

JP sat in the rocking chair in the living room. “See this, skeejins.” He pointed to his sandwich. “This is an Indian sandwich. We got some nice thick white bread, a thin layer of mayonnaise, a dab of ketchup, some shredded cheddar cheese, and then three slices of bologna.” He took a bite.

“How does that make it an Indian sandwich?” I said.

JP looked at me and then at his sandwich. “Because I’m eating it, that’s why. Don’t ask stupid questions, David.”

Tyson and I laughed.

I split one more cigarette with Tyson and JP before I decided to go home. When the smoke was butted I went to Tyson’s bathroom and peeled the Band-Aid from my face. In front of the mirror, the cut looked worse than earlier, but better without the Band-Aid. The chance my mother noticed the cut was less without the Band-Aid, but if she did notice it, I preferred that she see it for what it was: a wound.

Frick’s truck was gone from the driveway when I got home. The wind blew, and yellow and orange leaves twirled in the road. I opened the mailbox at the beginning of the driveway. Nothing but a dead hornet that had been there for months.

Mom was sitting in her rocking chair with the TV remote in her hand. “Where’s the mail?”

I unzipped my jacket. “There was nothing.”

Mom stood, and she walked with a limp. Arthritis. She was as hot as the woodstove. “Where’s the phone,” she said, but it wasn’t a question.

I made it down the hallway to my room before she spoke: “Come back and call your father.”

I tossed my jacket on my bed.

“Here.” She handed me the phone and I dialed his number. It rang. Mom hovered not too close, but close enough. I turned my bruised and split face the other direction. The phone rang. Mom looked in the cabinet under the sink where she kept all the poisonous fluids. I wondered how many times she had checked under there today. The phone rang. I hoped he’d answer, an end for today. Like undone chores, these missed calls piled up.

It rang. The kitchen table was clean: not a pork rind in sight. I dug my finger into the small dent in the table, formed when Mom and Dad and Paige and I had all lived together. It was one of the few memories I had of that time, and the memory was as sharp as glass. On top of our fridge, Mom had kept a heavy jar filled with nothing, and it had fallen onto the table and left a perfect, smooth indentation. The jar never broke.

The phone rang and rang. Mom slammed the cabinet shut, and the voice on Dad’s automated voice mail said his inbox was full. I pretended to leave a message, to please her, and then I hung up.

“Your father.” Mom took the phone and dialed his number again and again, each time hanging up before the automated voice said the machine was full. I turned my face away from her and smelled for the first time the corn fritters she’d made. Not a trace of their preparation or their cooking remained—she had cleaned everything. The only dirty dish was the one upon which the fritters sat, cooling. The garbage bin was empty too, the bag white like fresh snow.

Frick’s truck groaned up the road, and Mom set the phone down and watched him pull in. He got out of the truck, and he kicked shut the driver’s door. He cradled in one hand a large brown paper bag—the bag wet, the chilled bottle having heated and sweated in the hot truck—and in the other hand he carried a bag of pork rinds.

Dad called later in the evening, but Mom and Frick were out back of the house around the fire.

“Hey, buddy,” Dad said. He was fully awake. “Whatcha doing?”

“Just got done eating.”

“What’d you have?”

Dad loved all food. Even if it were a can of tomato soup, he’d spend all day with it on the stove at a simmer, struggling against his weight to get up from his chair every thirty minutes to stir it and add dashes of salt and pepper.

“Corn fritters.”

“The ones your mother makes? Those are good. What’d you have with them?”

Peace and quiet, I felt like saying. When Frick had come back, he and Mom went straight outside and I had brought six corn fritters back to my room, shut my window so as not to hear them, and ate.

“Mom made some soup.”

“What kind?”

For fuck’s sake. “Chicken noodle from a can.”

“She’s cheap.”

“Mom said you were supposed to send money up in the mail.”

“What?” He groaned, and I could tell he was trying to sit straighter. “I sent her money two days ago. Did you get any of it?”

Did I get any of it? “No.”

He started to cough. “Hold on, David.”

I moved the phone away from my ear until he was done with his coughing fit.

“Shit,” he said. “You there?”

I told him I was.

“I sent her monthly money and then some.”

“Mom said you haven’t sent anything since my birthday.”

“That fucking liar. I did too. I sent four hundred.”

“Earlier this month?” I said.

“Yeah!”

I didn’t know what to say, but Dad always said something when I was quiet.

“I can Western Union a hundred dollars tonight,” he said. “But I’m sending it in your name.”

“Just send it in her name.”

“You don’t want any of it?”

Frick passed by my bedroom window, and he carried an armful of wood. “Fine,” I said. “Send it in my name. You will send it tonight, won’t you?”

“Yeah, yeah. I’m going right now.”

I put the phone on the hook and looked at the clock. Seven thirty.

Mom came in the front door without Frick and I turned to hide my gash.

“Kwey, gwus,” she said. “It’s chilly outdoors, but the fire’s nice. Come sit outside with us.” The last thing I wanted to do was sit outside with the two of them. It was awkward when they started to bicker; I had nothing to do but sit there and listen. If I moved, my mother would say to Frick, You’ve upset my boy.

“I’m all set,” I said. She looked hurt. “I mean I would, but Dad called. He’s Western Unioning some money.” “Oh? What happened to the money coming in the mail?” She walked to the sideboard, picked up a cold corn fritter, and bit into it.

“I didn’t ask,” I said. “But he said he sent four hundred at the beginning of the month.”

Mom thought that was funny.

“That’s what he said,” I told her.

“When’s he sending it?” she asked.

“Right now.”

Mom took another bite of the corn fritter. “I think I can drive,” she said.

“No need,” I said. “He’s sending it up in my name.”

She stopped chewing. “Your name?”

I shouldn’t have even told her. “I offered to go and get it.”

“How much is he sending?”

“Eighty.”

She turned away in disgust and threw the rest of her corn fritter away.

“Better than nothing,” I said.

“Sounds about right for us.”

I went to my room and grabbed my jacket. The back door slammed shut behind Mom and I pulled my cigarettes out. One left. In the kitchen, I looked through the window above the sink at the fire. Mom and Frick were sitting there, guzzling whatever had been in that paper bag. I hurried to Paige’s dusty room and turned on the light. I opened drawer after drawer, searching for a loose cigarette. I found one way under her bed, right next to a blue pill and several bobby pins.

Before leaving I wrapped two corn fritters in a paper towel and tucked them in my pocket. Outside, the sky was clear and my breath mingled with the stars. I didn’t want to make the walk to Overtown by myself, so I walked down the road to Tyson’s and knocked on his door. He was all for it. He didn’t even put his shoes on inside—he grabbed them and started walking and put them on as we walked down his driveway.

The Island was quiet and dark. Houses were awake if their outside lights were on; houses were asleep if you didn’t see them in the dark, if all they seemed to be were masses of dense black pulsing between the surrounding trees.

We passed the church, and the sign under a white light read “Sunday ass.” I pointed to it and we laughed. When we crossed the bridge and were in Overtown I pulled Tyson down a path to the riverbank, and we stood under the cold belly of the bridge. I flicked my lighter, flame casting shadows over steel, and the flame sizzled against the tobacco. I let go of the gas and I wondered what all the shadows were.

I took a drag. “I found this under my sister’s bed.” I passed it to Tyson. “It’s a Newport. Tread carefully.”

When we finished the cigarette and were back on the road, I pulled the corn fritters from my pocket.

“Want one?”

Tyson took it in his hand and inspected it under the street light. He bit into it. “What is it?”

“A corn fritter.”

“It’s pretty good.” He swallowed hard. “Little dry.”

Main Street came into view, and people floated like dust outside the bar. We crossed the street to avoid them and continued the road to Rite Aid. The parking lot was empty except for the dull orange light from the streetlamps beating down on the concrete. Tyson stayed outside. I squinted in the bright light of the store and leaned on the counter while I filled out the Western Union form. The only ID I had was a tribal one and the cashiers never accepted it, but there was an option to set a security question-and-answer system to verify who you were. If whoever sent the money asked the same question and gave the same answer as whoever received the money, then that was valid enough proof.

What is your favorite color? I wrote. Dad always put blue, but I didn’t know if that was his favorite color. Blue, I scribbled. Well, maybe he was asking what my favorite color was?

The cash register cha-chinged and the attendant handed me five twenties. Three stiff, fresh bills and two floppy, smooth ones. No matter the condition, I knew each bill smelled of a million dirty hands. I thanked her and before I got outside I slid one twenty in the pocket with my pack of one cigarette.

On our way back to the rez, people were outside the bar smoking. We passed by on the other side of the road and Tyson and I felt them staring.

“Hey,” a fat guy said. “You got a cigarette?”

Tyson yelled back. “Look in your hand!”

“I’m holding this for someone! Come on, you got a cigarette?” He walked out from under the streetlight and into the dark of the road. “Come back.”

Tyson and I kept walking toward the bridge.

“Greedy fucking Indians!” He yelled. A roar of laughter came from all the men. “Can’t spare one lick of tobacco!”

We stopped.

“Let’s tie our shoes,” I said.

We knelt down. I checked my laces and they were knotted tight. I searched the ground for rocks. When I stood, I had a handful.

“Ready?”

We turned back toward them.

“Atta’ girls!” Jabba the Hut said. “Bring me a cigarette.”

We got as close as we needed.

“What are you dicking around for?” His voice was calm, and he held out his hand. “Come on,” he said. “I won’t bite.”

I leaned toward Tyson. “Throw that rock like you threw that stick at my face.”

“I’ll throw it harder,” he said.

I counted to three and we let them fly. The fat man was the first to duck and the others closest to the bar door tried to go inside.

“You dirty fucking Indians!”

Glass shattered, sprinkled all over the sidewalk. Men rushed out from the bar and the fat man stood. “You’re fucked now, girls!”

Tyson turned first and then I followed, sprinting ahead of him. I didn’t look back but it sounded like footsteps.

“The swamp, head to the horse bridge!”

I ran so fast across the bridge to the Island that everything was a blur. I passed the church, I knew that much, and soon I found myself near the swamp. I veered off the road and into the woods, twigs snapping and leaves crunching underfoot. I stuck my hands out to protect my face from tree limbs. The moonlight lit the swamp and I avoided the pools of murky water, hopping from one small patch of mossy ground to the other, until those patches got fewer and fewer the closer I came to the river that crept inland and formed the swamp.

A fallen tree closed the gap between the swamp and the path along the riverbank that led to the horse bridge. I was out of breath when I stepped carefully on top of the fallen tree and wobbled across to the other side. Even, flat ground. I took one deep breath and floored it toward the horse bridge.

With hands on my knees, I tried to listen. All I heard was ringing in my ears and my heavy breathing.

I waited. My breath slowly came back to me and my ears stopped ringing. Five minutes passed, then another, and Tyson didn’t show up.

I wondered what time it was. Panic crept over me. But soon I heard footsteps coming down the opposite way of the path. It sounded like feet were sliding, dragging across ground.

I hid under the horse bridge and the feet scuffed against the wood above my head.

“David?” A voice whispered.

“Below.”

He was breathing hard and the moon off the river divided his face. We stared at each other until we erupted with laughter.

“Oh, man.” I wiped the tears away from my eyes. I had laughed so hard I cried.

“I gotta get home,” Tyson said, still laughing.

“Me too.” I reached in my pocket. “Let’s smoke this last cigarette while we walk.”

Tyson told me that he couldn’t go into the swamp. Someone was chasing him and was too close, so he led them farther up the road before turning down a path. He ran until he was sure he shook whoever it was and then cut through the woods. He’d already overshot the horse bridge and so he found the riverbank and came back toward it.

“I thought you were done for,” I said. “My heart was pounding.”

“You think we’ll get caught?”

“For what?” I asked.

“Breaking that window.”

“When did we do that?”

Tyson laughed. He took one last drag on the cigarette and put it out. We came out onto our road and we split off in opposite directions, his feet dragging farther and farther away.

Frick’s truck was gone. I looked out back of the house at a dwindling fire. Coals popped and little red sparks died in the cold air. Inside, the clock read ten. It felt later than that. Mom was in her rocking chair, sleeping, her head crooked sideways.

I shook her arm. “Hey,” I said. She jumped awake.

“You scared me, gwus,” she said, slurring her words. She shut her eyes again. “What time is it?”

“Ten.”

She rocked forward and tried to stand. I grabbed her by the elbow and helped her up. I guided her down the hallway to her room.

I gave her a good-night kiss and she shut her door. I went around the house turning off all the lights. On the cedar chest in the living room, Mom had left her pack of Winston 100s and I stole three. I put one in my mouth but didn’t light it. In the kitchen, I spread the four twenties out on the table so they covered the small dent. Before I went to bed, I went around the house collecting ashtrays. I dumped them into the garbage, and ashes and filters sifted down over Mom’s half-eaten corn fritter.

The morning was cold, and my heart thumped. The sunlight lit my room, the trees outside too bare to shield this side of the house. Shivering, I pulled my blanket tight around my body and thought of the bar window and all the ways we would not get caught.

I sat up. I had to tell Tyson not to wear his orange jacket today. With the blanket wrapped around my shoulders I dragged myself to the kitchen. The floor was cold through my socks. I looked out the kitchen window at the oil-tank meter. Less than an eighth of a tank. The woodstove wasn’t burning, so I filled the base of it with crumpled newspaper and then wrapped kindling in some more, lighting it all up with a grill lighter. When it was ready, I fed logs into the fire.

It was quarter to eight. We were out of coffee filters, so I stuffed a paper towel into the coffeemaker and filled it with grounds, and then I poured eight cups water into the back part. I plugged in the coffeemaker, and it screamed and gurgled.

I heard a quiet voice over the sound of the coffeemaker and the popping of the woodstove. “Gwus?”

Mom was up.

I opened her door and peered into the darkness. Her curtains were blacker than mine and the sun didn’t rise toward her windows. “Yeah?”

“Bring me some juice?” She didn’t open her eyes.

“You want coffee too?”

“No, just juice. I’m going to rest some more.”

I got her juice and set the cup on her nightstand.

She picked it up and took a sip. “Thank you.” Her voice was grateful, as it usually was when she needed something.

I poured a cup of coffee and set it on the cedar chest in the living room and while it cooled I went to my room and made my bed, straightened the corners of the red comforter, and when I finished I went back to the living room and sat on the couch and picked up the coffee and blew on it. I wanted a smoke. I didn’t know if Mom would get up to use the bathroom, but after tapping my foot on the floor for a long time, I went to my room, shut my door behind me, and cracked the window.

The sun was bright on my face and the first drag brought me to myself. Smoke filled the air and showed the sunrays. I remembered the cut on my face. It was tender, coarse, hard. I picked at it the way my father picked at the sores on his legs. It wasn’t ready to peel. Fresh blood dotted the tip of my finger.

By ten thirty Mom wasn’t up. I crept in her room, and I shook her arm.

“Hm?”

“I’m going out for a bit,” I said.

“What time is it?”

I told her.

“You want to bring me coffee?”

I poured her coffee and put five sugars in it.

She grabbed the cup and sipped with shaky hands. “Thank you, honey.”

I inched toward the door, had my body turned sideways so she couldn’t see the cut.

“Where you going?” she said.

“To Tyson’s.”

“You eat?”

“No, but I’ll take a few corn fritters with me.” I wasn’t hungry.

“Come home for lunch, I’ll fix you something. What do you want?”

“Grilled cheese?” I said.

“We don’t have any bread.” Mom laughed. “I’ll ask next door.”

I dressed, grabbed a corn fritter, and went outside. Out back, frost sparkled on the tips of grass around the fire pit. An open tin coffee can filled with sand and cigarette butts held down an empty pork-rind bag in the wet grass. I took some long-butted Winstons, and then I found the lid to the can and snapped it on. I cut through the woods to Tyson’s.

When I showed up to his house, he was eating a bowl of Lucky Charms, and when he finished and brought his bowl to the sink and came back to the couch he turned on his Xbox and handed me a controller and we played three matches of Halo until his dad left, and we tried to play a fourth match but we grew sick of it, and so we went on his mother’s computer and tried to watch porn, but the videos wouldn’t buffer.

“You have Lucky Charms cereal, yet you have shitty internet?”

Tyson laughed as he cleared the browser history.

“Let’s go smoke,” I said, and he was saying his dad might be back soon.

“Boiler room,” he said.

We smoked in the boiler room, yet it was so hot we didn’t even finish our cigarettes and went back inside. Tyson put on jeans and a fresh black shirt. He asked if I wanted to go to the social, the powwow at the football field. I told him my mom was making lunch, and right then I remembered the bread, remembered his jacket. I persuaded him to wear a different one.

At noon, before I left Tyson’s, I stole four pieces of white bread and put them into a sandwich baggie. It had gotten much warmer outside. I carried my jacket over my arm and rolled up my sleeves. I rounded the corner of our road. Smoke rolled out of our chimney and into the sky. The door creaked shut behind me, and Mom’s hair dryer was whistling from the bathroom. I rolled my sleeves down.

“Ma?” I yelled.

“Be right there.” She turned off the hair dryer.

I sat at the table and the money that had covered the small dent was gone. Mom came out. “Oh, shoot,” she said. “I forgot to go ask for bread.”

I held up the baggie with four slices and smiled.

“David,” she said. “What happened to your face?”

Shit.

She took the bread from my hands but didn’t take her eyes from the cut.

“A stick,” I said.

She put the bread down next to the sink. “I told you. You fucking kids don’t listen.” She meant Paige and me.

“It’s fine,” I said. “Relax.”

“It won’t be fine when one day you’re blind. You already lucked out once bef—.”

“I know,” I said. Don’t bring it up, I thought, and she said no more.

She sprayed a frying pan and turned the burner on medium. We were quiet. When the pan was hot she buttered one side of each slice and lay one down in the pan. It sizzled. She put two slices of cheese on top and then lay the other slice down, buttered side up. She flipped the sandwich over and it sizzled, hotter and louder. She turned the burner lower.

While the other side cooked she went in the bathroom and put on makeup. After a while, she hollered at me. “Check your sandwich, David.” With the spatula I peeked under the sandwich. It was black. I lifted it out of the pan, set it on my plate, and carried it to the table. The phone rang.

“Pew, you burn that sandwich?” Mom said. She picked up the phone. “What?”

The sandwich crunched between my teeth. Here we go, I thought.

“Why haven’t you called?” Mom took the phone to the bathroom with her and on the way she moved the phone from one ear to the other. “What do you mean they only let you use the phone once in a while? You can use the phone all the time there.”

Mom listened. “I don’t know,” she said. “How are you? How’s the program?”

“What’d you say?” Mom paused, and she leaned out the bathroom and looked at me. “He’s fine. Listen . . .” She was serious. “Hold on.” Mom left the bathroom and shut herself in her bedroom.

The house was quiet except for the hum of the fridge. I leaned in my seat toward the hallway, trying to listen. Nothing. I took a bite of my sandwich, set it down, and chewed and tiptoed to the hallway.

I heard words, sentence fragments, incoherent and jumbled. There was no context unless I gave them some. Eventually, I heard all I needed to: “He’s stealing my cigarettes.”

My stomach dropped and I wanted to puke. Mom had this way to make you want to die. I brought my plate to the sink and then sat in the living room. I looked at Mom’s pack and didn’t even want one.

Soon, Mom came out of the room and put the phone on the hook. She didn’t ask how the sandwich was. “I’m heading to Overtown soon,” she said, returning to the bathroom, and in time Mom’s makeup container snapped shut, and when she came out of the bathroom she said nothing to me and left. I could do no wrong when Paige was around, but the moment she was gone, the world in which we lived became my fault. I scraped the black burn off my grilled cheese.

The house was quiet when Mom left, except for the crows cawing outside. I put on my jacket and went out to find JP and Tyson. Crows cawed louder; they were in the trees and on the power lines. Through the woods I walked and smoked. The trees were bare, and the sky above was a piercing blue. The smoke made my eyes water, and it was like I was drowning.

My stomach growled. I hopped over a fallen tree and continued down the path until I heard cars passing on the road. I finished my cigarette and walked onto the street toward Tyson’s, but he wasn’t home, was at the Social with JP probably. I cut through more paths until I came out on the other side of the Island, where the football field pressed against the river.

No one was drumming and not too many people were left at the Social. People clumped together in small groups that speckled a third of the field. JP and Tyson were sitting on the side of the field tossing rocks into the river. Tyson was wearing a black jacket. I walked over and sat next to them.

“You missed some good burgers,” JP said.

“They’re all gone?” I wanted one.

He nodded. “A lot of people showed up.”

“I’m surprised they’re not drumming,” I said.

“Only one drum group came. There’s a powwow up north. You got a ciggie?” JP said.

“Just butts. They’re good length though.”

He wiped his hands together to get the dirt off and stood. “Better than nothing.”

“You want to go now?” I said.

“Everyone’s leaving.”

I didn’t want to move, didn’t want everyone to leave, didn’t want the food to be gone. But it was over. We left, and in the woods away from everyone we huddled together and I gave them each a half-smoked cigarette.

“Damn,” JP said. “Butted Winstons are strong.”

I nodded and lit mine. JP didn’t mention the bar window, so I knew Tyson hadn’t told him.

“Let’s go down to the river and watch the sun set,” JP said.

“That’s way on the other side of the Island,” Tyson said. “And it’s getting cold.”

“Shut up,” JP said. “If you’re cold why’d you wear a windbreaker? Going jogging?”

I laughed.

“Yeah,” I said, “Why aren’t you wearing your good jacket?”

Tyson shook his head and smiled. Then we were laughing. Really laughing!

“What?” JP said.

I caught my breath. “Let’s walk and we’ll tell you.”

The river drained into the setting sun.

“I would’ve smashed that guy’s head,” JP said. “At least you broke the window. That counts for something.”

I lit another butt. “I feel so much lighter now that we told someone.”

Tyson nodded. “Yeah, my dad asked this morning if I saw anything.”

“Wait, what?” I asked. “Before I came over?”

“Yeah.”

“And you’re just now telling me that?” I shook my head. “You’re ridiculous.”

JP poked Tyson’s rib cage. “Why didn’t you tell David earlier?”

“I forgot!”

“What’d you tell him?” I said.

“Who?”

“Poke him again, JP.”

“Stop!” Tyson scooted over some. “Who?”

“Your dad, dumbass. Who you think I’m talking about?”

“Oh, yeah. I said we didn’t see anything. Then he didn’t ask me anything else.”

“That’s the most anticlimactic story I’ve ever heard,” JP said.

We were quiet and smoked our butts. After those, I had none left. The sun was setting fast and a few bright stars dotted the sky.

“I wish I’d been there,” JP said.

It was dark when I got home. Frick’s truck was parked behind Mom’s car. No lights were on in the house. Mom’s laughter poured out from behind our neighbor’s backyard, where a fire burned hot and fast, and her and Frick’s shadows pressed against the edge of the woods, swaying.

The house was cold. I turned on the kitchen light, went over to the woodstove, and touched the icy steel.

I dug in the wood box for newspaper but there wasn’t any. On the kitchen table some bills lay sprawled as if they were thrown, an empty brown paper bag upright as if set down gently, and a pile of that day’s local paper was neatly stacked. Mom always brought them back from the store for the woodstove.

I put the local papers in the wood box but kept one out, and I glanced at each page before I crumpled and stuffed them in the woodstove. A story about a 5K fundraiser, accompanied by a large picture of a woman running, covered most of the front page. Another story came below, something about a bill for higher taxes, and continued on to a later page. Stories of animal shelters overflowing and grand openings of stores that never lasted and the governor’s new plan for more jobs seemed to compose in no order the paper. There were stories on retirement homes and even a story of a car salesman’s journey to sales titled “Transformer.” They all had stupid titles.

I continued to glance at, crinkle, and toss each page into the woodstove until my eyes fixed on “Crime and Court.”

I froze, fingers clenching the paper.

Rock ’n’ Roll

Police say that last night a local bar had its windows smashed out in what they’re calling vandalism. According to the police report, at 8:45 PM, patrons of the local Overtown Bar stood outside smoking when two teenage boys approached them and asked for cigarettes. When the patrons refused, the teenagers became infuriated and began to harass them, eventually picking up rocks and throwing them toward the establishment.

The two boys have not been identified, but the report suggests that they are from the Panawahpskek Nation. According to the patrons, the boys ran toward the reservation. Overtown police are working closely with Island officers on the matter.

If you have any information about this crime, please contact the Overtown Police Department or the Office of Tribal Corrections.

I laughed, but I was angry, too. I ripped the story out, folded it up, and slid it in my pocket. I reached in the wood box and pulled out every local paper. One by one I crinkled up the “Crime and Court” page and put it in the woodstove and then neatly reorganized each newspaper and set them in the wood box. I took a front page and wrapped it around some kindling. I lit a match and touched it to the paper, and the fire crept and crept over the woman running on the front page, and I watched her disappear in the woodstove’s twisting flame. I took the fire poker and prodded the fire, which whooshed. I opened the damper and touched the warm cast iron.

I flicked on my bedroom light, and when I sat on the bed I saw it.

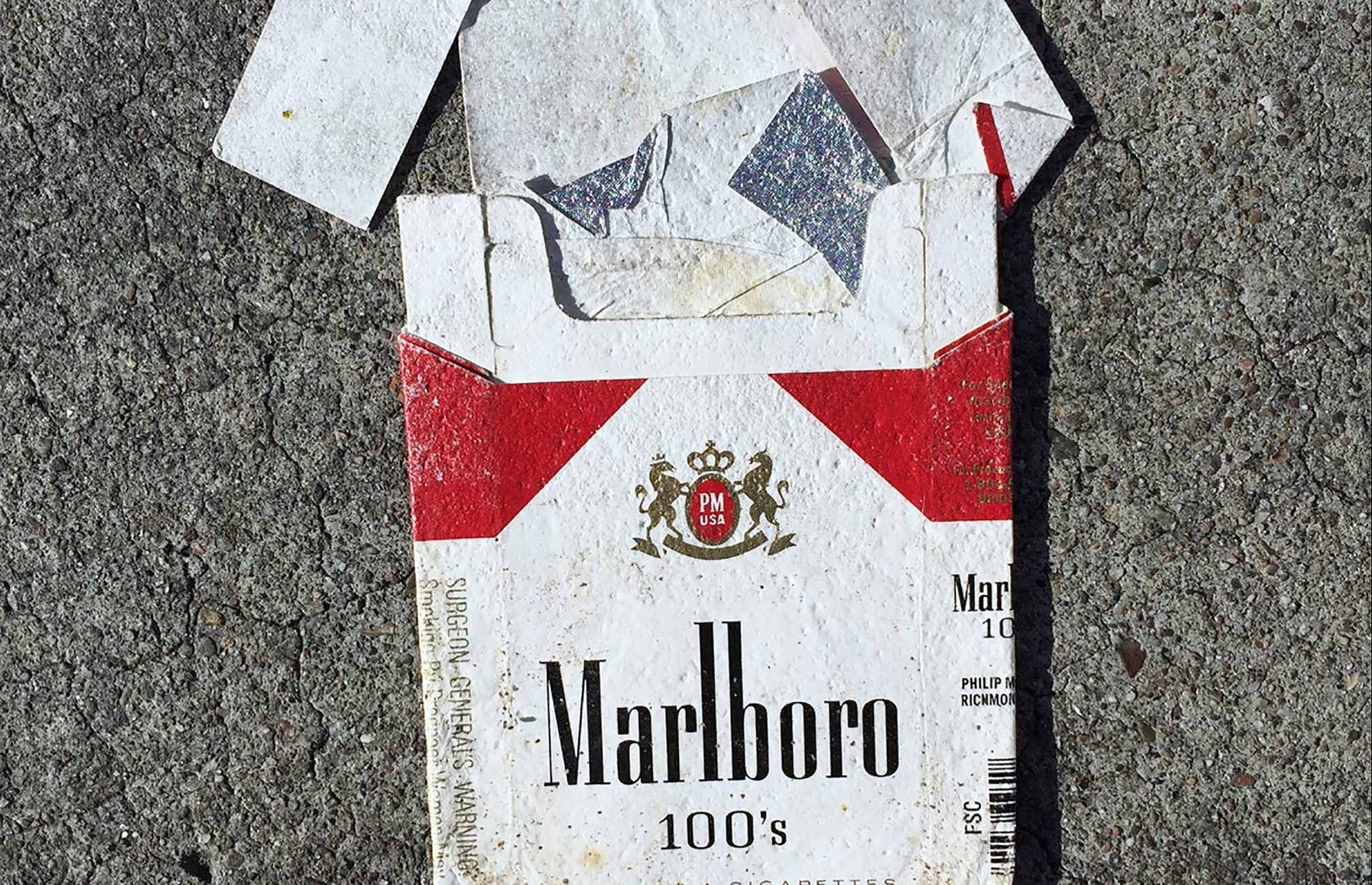

I got up. On top of my dresser stood a pack of cigarettes on top of a note. I held them. Winston 100s. I picked up the note. Mom’s handwriting.

Make them last, it read.

I folded the note and put it in my pocket with the news article. I undressed, turned my light off, and crawled under the covers. A small breeze slipped under the cracked window behind me and carried with it the sound of my mother’s laughter.