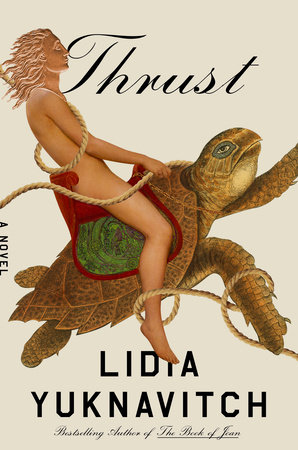

Laisvė, a character in Lidia Yuknavitch’s new novel Thrust, is in the water a lot. Water serves as a conduit for her to move between space and time, a power she uses to save other beings from manmade terrors like a ruined earth and an ever-encroaching police state. In the not-too-distant future in which parts of the novel are set, the surface of the earth is largely covered in water; even the Statue of Liberty is submerged. While the setting carries some connotation of bleakness, there is also a sense of hope.

Thrust isn’t based so much on plot as it is a kaleidoscopic confluence of different storylines. From impassioned letters exchanged between Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the real-life French sculptor who designed the Statue of Liberty, and his invented lover, Aurora to segments written from the plural point of view of the Statue’s workers to characters haunted by devastating personal histories to raids conducted by a dystopian future government on citizens, the book chronicles violences big and small that have shaped the course of humanity. And, the novel offers hope in the idea that stories, ever-changing, have the power to carry Laisvė—and others—somewhere new.

I spoke to Yuknavitch over Zoom about living as part of an ecosystem, expressing iterations of grief, and how novels can jostle us into new ways of being.

Jacqueline Alnes: The Statue of Liberty is arguably one of the major characters in this book, or at least one of the most noticeable threads. “Liberty,” as a word itself, suggests freedom in all senses: emotionally, physically, politically, economically, etc. but obviously not everyone in the book, nor in our current world, is free. I figured I’d give you the biggest question first, which is: What does liberty look like to you?

Lidia Yuknavitch: That’s at the heart of Thrust in more than one way. Liberty is beautiful and vital as a possible story. Unfortunately, humanity has packed it with shit. We make those kinds of mistakes of interrupting liberty or binding liberty or making liberty exclusive to some at the expense of others. That’s what I mean by packing it with shit. It becomes about power. For me, the beautiful story is ever-possible and ever-changing, but what we’ve found ourselves doing for epic after epic is, from my point of view, a series of horrible violences and otherings.

JA: Did jumping back and forth in time in the book, between past, present, and future, help you notice those threads related to liberty more clearly?

LY: Humans love linear time because it’s comforting. But if you push linear time to the side over there (and give it a graham cracker, so it’s okay) then I was fascinated by the idea that epics might be in dialogue with each other rather than that old tired out notion that history is the past or the cliche that we are doomed to repeat the past. Those are uninteresting stories to me. A more interesting story is: What if you could dislocate periods and move them around like words in stories and let them talk to each other?

JA: I wanted to talk to you about the loosening of boundaries between animal and human life. Not to be too on the nose and be like “animals have a voice,” but they do in this book. For so long, it seems like written and spoken word have been privileged, at least by the colonizers of any place. But in this book, animals can talk back. I haven’t looked at an earthworm the same since reading this. When I garden I’ve been saying, “Hello! Greetings!” How did being in the world influence your writing of the animals in this novel?

LY: I don’t perceive animals in an existence hierarchy as lower than humans anymore, if I ever did. I certainly don’t now. I live in a forest next to the ocean at this point in my life, so I see more animals than people on a daily basis. That has impacted me.

But it tracks back to childhood. In childhood, we believe we can talk to animals. We believe they say something back. There was a lateral possibility in the story-space and the imagination was part of it. I’m not meaning to make it a traditional children’s book where there are talking animals who are magical beings. They’re not meant to be magical. They’re meant to be realism. It’s meant to be true that Bertrand starts being sassy one day. It’s meant to be real that the worms are like, “We’re busy here! What do you want?” I’m also not trying to romantically anthropomorphize them. That wasn’t the intent. Instead, I’m wondering, what if there was a lateral conversation without humans at the top of the hierarchy? There would be some “here’s what’s what” talk, not some overromanticized drama.

JA: While reading Laisvė, she seems to want to know the world in different ways and loves in languages that were beautiful to me. She loves in knowing characteristics of other beings, she is very present in the world. Did you think about the decolonization of earth-human relationship while writing?

In the U.S., women still aren’t understood as fully human, but I don’t mean woman in a biologically essential way.

LY: Oh yeah. Laisvė is kind of an attempt to say there are other ways to be human—because there are other ways to be human. In my own childhood development, I had some elements of my being that we now understand as having been on the spectrum. I had pica, which means I ate things like pennies and dirt and rocks and paper.

JA: I ate dirt too!

LY: I knew I recognized you. People have all different ways of seeing and receiving the world and the so-called health community thinks of that as a divergence from being “normal” or “healthy” or “full” but we don’t. I was very invested in making a character whose very different ways of experiencing the world are the possibility of changing the story. So when a person with synesthesia, for example, tells you what it’s like to be them—which Laisvė has going on too—her relationships, her life, her ways of being in the world are completely different than someone else’s would be. That we would leave something like that out of the story of who we are is yet another kind of violence.

JA: There’s a real thread of climate crisis in the novel. Parts of the East Coast are underwater and the Statue of Liberty is as well. What was it like writing this reality, and how did reflecting on our current reality (and our own actions/inaction) shape your perception of climate change and how it will impact future generations?

LY: From my point of view, we are already there. I just turn the volume up. You can re-present the world and sure, it’s in fictional terms, but I’ve done heavy duty research on ocean rise and climate change. We’re already there. I was just lamenting to a friend about what’s going on with the Great Salt Lake, which anyone can Google and see uh-oh. The point where the dial went too far I believe already happened. It matters what we tell each other right now about who we are and what we are going to do.

When I wrote into that realm, I was just trying to be precise about the present tense. I don’t think that a story like mine has any power to change the world, but I think novels can jostle us and I think it’s important we jostle each other in our understandings of each other and the world. I think they are part of the thing that can create change.

JA: At one point, Laisvė admires the shapes and colors of the turtle—its shell, the creature’s toenails. And she wonders: “Why had she been born a human girl?” Girlhood and what it means to come of age in turbulent times—as well as finding meaning through water—are themes in this novel and in Chronology of Water. I’ll ask a similar question as Laisvė: Why a girl as the protagonist? Why Laisvė in particular?

LY: Just so you can hear what it’s like from my side of making the story, I think she’s a floating signifier more than a protagonist. She’s an energy pulse who moves between time, space, people, plants, and animals and jostles things or makes them vibrate.

As I conjured her, I thought about how human embryos do sort of look like animal embryos for a while there, before they get really human. And that fascinates the fuck out of me. I can see where humans could have had tails and when I look at shoulder blades I think that’s where our wings used to be. When I look at hands, there are certain creatures like dolphins and whales whose fins had the possibility of fingers for a while but they went flipper. And so those truths get inside my imagination and start blooming. For this girl who sees everything differently, she thinks we are all creatures. And it’s a way to take that hierarchy down of humans on top and imagine that if we all saw each other creature to creature, we would definitely treat each other differently.

And the girlhood thing is important to me as a space of meaning, not so much just girls, because a boy could be in there. I’m still trying to loosen the binary so those words aren’t as important at all: girl or boy or man or woman. In a world from my point of view, the day you come out of a chute, if you’re a girl, you’re entering the world fraught with energy coming at you that asks that you either serve society as a caretaker or wants you kind of erased or dead. It disallows full agency. In the U.S., women still aren’t understood as fully human, but I don’t mean woman in a biologically essential way. I mean the space of a woman. We have hard work forever in that category.

Every book I write I’m trying to shake the word “girl” and “woman” and maybe not get rid of those words, but I think we need better subject positions that give people their full autonomy and agency. These words that are locked in a binary don’t work any more and they are part of the problem.

JA: I’d rather be a creature than a woman, I think. I want to talk to you about water, too. In this novel, water is a means of travel, a place teeming with life, a space of grief, a place that holds deep, deep memories and love. It’s also safe, despite the depth. What did you find in the water while writing this book?

Whether or not it’s in my lifetime—and it probably won’t be—I hope that our definitions of who we are and the stories we are telling each other change radically.

LY: Specific to Thrust, I’d say my daughter died the day she was born and her ashes are in the ocean. Laisvė has some of that in her: the ocean is life and death. Laisvė can be in and out of it. I think of what’s happened to my daughter’s ashes in all these years. I pick up a rock and think, is she in there? Is she in another ocean by this point? I think of the ocean as a metaphor for very close intimacy with the imagination or the subconscious. I am not the first person who’s said that, but it’s true for me. When I stand near the ocean, I feel part of something I’m supposed to be part of. I feel that way about the imagination, too.

JA: That’s beautiful. Have you read Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs?

LY: Oh yeah.

JA: I’m thinking of the way whales drop to the bottom of the ocean when they die and their bodies feed and make beautiful the deepest part of the water that we never see.

LY: I just wrote about that! They make whole ecosystems. That’s exactly why I was talking about my daughter. The sea is a life-death, life-death, life-death motion in your face. It’s spitting shit on shore that’s both alive and dead every day of our lives and carrying it and holding it and making it into something else. It’s this incredible space.

JA:We’ve talked so much about agency and the power of story. Where do you hope our collective story goes from here?

LY: I definitely hope humans learn to see and love each other and everything around them differently than we have in… ever. Whether or not it’s in my lifetime—and it probably won’t be—I hope that our definitions of who we are and the stories we are telling each other change radically. I hope humans understand themselves as particulates of existence and not the owners of existence. What’s happening now in terms of the fluidity of gender and sexuality in generations younger than myself, I hope that takes over the world; it looks like the most beautiful way of being to me.

I think our differences can be so divisive, but I hope they become more fluid as well and that a kind of shared story space challenges us to do what you just said, where you’re standing around in your own life and you think, I’ve never thought about the whale carcass at the bottom of the ocean. To be honest, I’m not doing well with the divisions right now. Rage, rage, rage. But I guess a faster way to say all of this is that I hope adaptation and evolution bring us to something better than we are.