Solar power. The end of war. Gender role reversal. Dirigibles. First published in 1905, Rokeya Hossain’s short story “Sultana’s Dream” is steampunk avant la lettre, strikingly advanced in its critique of patriarchy, conflict, conventional kinship structures, industrialization, and the exploitation of the natural world.

Notably speaking to the concerns of our contemporary world as much as its own, it is also striking for being a parodic critique of purdah by a Muslim woman. At a time when British colonialism was using the treatment of women in India as justification for colonial intervention there (a rhetorical strategy still in use by the West today), Hossain’s story imagines a world in which men rather than rather women are kept inside, thus framing her protest against Islamic patriarchy within a larger feminist vision that takes on Western as well as Islamic forms of gender hierarchy.

“Sultana’s Dream” is not just one of the first science-fiction or utopian stories written in India by a woman; it is an integral part of the emergence of sci-fi as a form of speculative fiction at the turn of the nineteenth century, more often associated with male Western writers such as H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Arthur Conan Doyle. At the same time, it is one of the first feminist utopias in modern literature, published a decade before Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915), and part of a wave of fin de siècle utopias that includes Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) and William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890). It is also one of the first literary works in English by a Muslim writer in South Asia. In all these ways, Hossain’s story is an important part of Anglophone literary history that has yet to be fully recognized as such.

It is all the more remarkable, then, that ‘Sultana’s Dream’ was written in her fifth language by a woman who was denied a formal education.

It is all the more remarkable, then, that “Sultana’s Dream” was written in her fifth language by a woman who was denied a formal education (she also knew Urdu, Persian, Arabic, and Bangla). The Muslim community in India at the time largely did not approve of education for women, and the colonial government, though it had a college for Hindu women, did not open one for Muslim women until 1939, close to the end of the British imperial rule in India. Promoting education for girls and women was thus Hossain’s passion, as evidenced by the stories and essays collected in this volume; it also shaped her career and political work and is one of her enduring legacies.

Rokeya Hossain (1880–1932), known by the honorific Begum Rokeya, is widely recognized in South Asia today as a pioneering educator, feminist, writer, and activist. Because she lived and worked in a region of colonial India that is now part of independent Bangladesh, she is a particularly revered public figure there and is celebrated every year on December 9, otherwise known as Rokeya Day.

India was ruled by Britain from 1857 to 1948. The idea that the English language and literature was superior to Indian languages and literatures, and should therefore be taught as widely as possible, was a racist justification for Britain’s prolonged rule and a tactic of governance: many desirable government jobs required an English education, so it came to be seen as crucial to social, economic, and political advancement. This is part of the reason Hossain educated her children in Britain, wrote “Sultana’s Dream” in English, and argued that Muslims should pursue English educations so they would benefit from the vocational advantages that accrued to those who could speak and write in English. But she was also deeply critical of British rule and its imposition of cultural norms on India; in Padmarag, Tarini Bhavan, a women’s school, workshop, homeless shelter, and hospital, offers a broad and Indian- centered education so that its students would not be “forced to memorize misleading versions of history and end up despising themselves and their fellow Indians.”

Hossain’s story [frames] her protest against Islamic patriarchy within a larger feminist vision that takes on Western as well as Islamic forms of gender hierarchy.

Hossain grew up in a traditional Muslim family. Her father had four wives, favored education for his sons but not his daughters, and imposed purdah: a Muslim practice, also employed in some Hindu communities, where women live in separate quarters to conceal themselves from men, and sometimes unknown women as well, and use veiling to cover their bodies when in public. As a result, Hossain had to largely educate herself by reading on her own, though she was helped by her brother, who taught her English (and to whom she gratefully dedicated Padmarag), and her sister, who taught her Bangla, the language in which she published most of her writing. Like many women at the time, she was married young, at the age of sixteen. It was an arranged marriage, but her sympathetic brother deliberately helped match her with a man, Sakhawat Hossain, who he knew to have more progressive views about

women’s education than their father. Her husband ended up not only being supportive of her writing—he encouraged her to publish “Sultana’s Dream,” for example—but also left her money when he died to set up a school for girls, thereby paving the way for her autonomy and ability to pursue her ideals.

“Sultana’s Dream” was first published in 1905 in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine. Edited by Kamala Satthianadhan, it was the first English-language periodical in India run by, and targeted at, Indian women; Satthianadhan’s daughter, Padmini Sengupta, wrote for the magazine and later served as its assistant editor. Both a Christian and an Indian, Satthianadhan saw herself as a syncretic blend of East and West and imagined her magazine this way as well, blending sympathy for Indian nationalism with expressions of friendship with Britain. Thus while hers was one of the first magazines to publish the poems of Sarojini Naidu, who would later become a prominent figure in the nationalist movement, it tended to shy away from publishing the kind of overtly anti-imperialist articles that came to dominate the Indian press by the early twentieth century. But like Hossain’s story, The Indian Ladies’ Magazine was more explicitly part of the burgeoning conversation about women’s rights and published the work of several influential feminists and activists. As well as Hossain and Naidu, it showcased writing by lawyer and reformer Cornelia Sorabji, socialist and politician Annie Besant, and educator-reformer Pandita Ramabai.

While Hossain is celebrated in the present day for her contributions to feminism and education, she endured bitter criticism in her own lifetime.

Satthianadhan’s gender politics, like her nationalism, were cautious; on the one hand, she promoted the idea that women should stick to the domestic sphere, on the other, she was interested in women’s rights and strongly believed in their education and right to participate in public discourse, as evidenced by her own path and that of her daughter. She was also, like Hossain, against the strictures of gender segregation and purdah, which no doubt motivated her inclusion of “Sultana’s Dream” in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine. But in a move consistent with the political balancing act typical of her journal, she went on to publish a satire of the story, “An Answer to Sultana’s Dream,” in the next issue of the magazine, which ends by restoring the gendered division of labor that Hossain’s story so gleefully subverts. The fact that this counterargument may have been authored by her daughter (the author’s name is listed simply as “Padmini”) suggests how radical Hossain’s story was and how careful Satthianadhan felt she had to be in disseminating it.

Although it was one of Hossain’s first published pieces, “Sultana’s Dream” would end up being her most famous. But she wrote for a number of contemporary periodicals and in a range of genres, including essays, stories, poems, and reportage, most often in Bangla. Her choice of language was an intervention in itself. Bangla was a regional language, whereas Urdu was considered the proper language of educated Muslims; as a girl, she had had to learn Bangla on the sly to skirt her father’s disapproval. But she developed a passion for the Bengali language, and since her goal was to shift public opinion in Bengal about women’s rights, she used Bangla as a way to address her community directly; she also made a point to teach it to her students. Her influential works written in Bangla include Motichur (translated as “A String of Sweet Pearls”), a collection of feminist essays in two volumes, and Padmarag (translated alternately as “The Ruby” or “Essence of the Lotus”), reprinted here. Though published in 1924, more than twenty years after “Sultana’s Dream,” it reprises many of that story’s themes, focusing on the injustices of gender disparities, on utopian female community, and on women’s education.

Another influential work by Hossain, The Secluded Ones, was published in 1931. Initially serialized in the periodical Mohammadi, it was later released as a single volume. Audacious both in form and in content, it documented the adverse effects of purdah on women’s lives by gathering together forty-seven anecdotes of absurd and/or tragic situations resulting from inflexible approaches to gender segregation. Hossain drew from her own experience as well as that of other women; for example, one of the anecdotes describes how as a small child she once had to hide under a bed in a dusty attic for four days so that visiting maids, who wandered freely around the house, wouldn’t come across her. The Secluded Ones was not only a significant feminist intervention but also important for having been written by someone who had both experienced purdah herself and who celebrated her Indian and Muslim identities, since many of the accounts of purdah that circulated before this were exoticized traveler’s tales by Western writers who often held derogatory views of Islamic culture and relied on second- or third-hand accounts of gender seclusion.

The protagonist, a Muslim woman living in contemporary India, wakes up in a transformed future world: a utopia in which women are free to explore at will and pursue an education.

The bulk of Hossain’s writing, as we have seen, promoted the cause of women’s education, either directly or indirectly. In an essay included in this volume, “God Gives, Man Robs” (1927), for example, she invokes the Prophet Mohammed to support her arguments. Since he commands that all men and women should acquire knowledge, she contends that it is wrong for men to stand in the way of the education of their wives, daughters, and sisters: not only is this a disservice to women and to Islam, she notes, but it also puts Muslims at a further disadvantage relative to the Hindu community (the dominant religious community in India), which was at the time engaged in a number of reforms related to women’s rights, including increased access to education.

“Educational Ideals for the Modern Indian Girls” (1931), meanwhile, spoke of uniting the religious and moral emphasis of traditional Indian education ideals with the secular knowledge important to twentieth-century life: “We must assimilate the old while holding to the now.” She advocated for a diverse and well-rounded curriculum that included art, physical education, science, horticulture, and health care—a pedagogical vision that is reflected in the utopian communities depicted in both “Sultana’s Dream” and Padmarag. Education for women, considered a break from tradition, is associated with modernity and thus with “the adoption of western methods and ideals.” But as in Padmarag, Hossain argues in this essay against the “slavish imitation” of the West and contends that domestic duties and older forms of knowledge should be integrated into female education, along with the kind of vocational training passed on from parent to child. While her appeal to the importance of feminine duty may have been in earnest or may have been an attempt to harness more widespread support for women’s education, this essay also contained an unambiguous and bold statement: “The future of India lies in its girls.”

Alongside this writing, Hossain devoted much of her relatively short life to hands-on educational work. In 1911, not long after her husband’s death, she founded the Sakhawat Memorial School for Girls in Calcutta (now Kolkata). A letter she wrote to the editor of the periodical The Mussalman appealing to the Muslim community for support shows how challenging and potentially controversial this undertaking was, despite the money left to her for this purpose by her husband.

By forming a collective, the women free themselves from the need for support from husbands or family: entities that the story often depicts as selfish, abusive, or uncaring.

Though Hossain ended up starting the school with only eight students, she persisted against bias in the Muslim community and had over eighty students in her school by 1915. Even while teaching and running the school, she was engaged in other forms of activism to promote women’s rights. In 1916, she founded the Bengali Muslim Women’s Association to cater to less privileged women (since women at her school tended to be from the middle and upper classes); much like Tarini Bhavan in Padmarag, it provided a variety of forms of aid, including shelter, community, financial help, and literacy. She was also involved in the organization of an All India Muslim Ladies’ Conference in Calcutta in 1919, where women’s education and polygamy were debated in the context of modern Muslim community; in a letter to The Mussalman in which she publicized the conference, she demonstrated her commitment to female solidarity by proposing to meet women traveling to the conference from remote areas at the train station and offering them free room and board at her school.

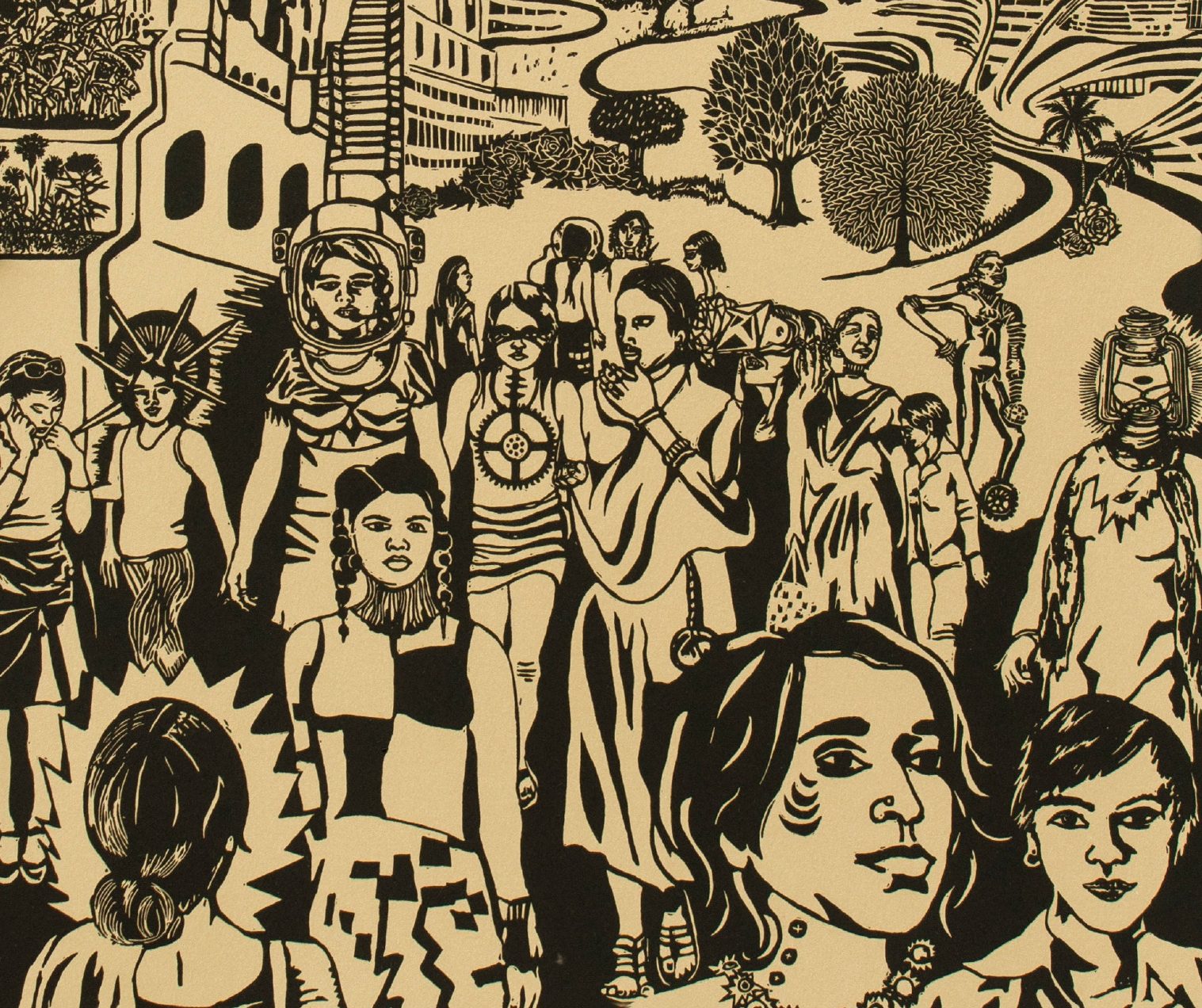

While Hossain is celebrated in the present day for her contributions to feminism and education, she endured bitter criticism in her own lifetime. Many members of the Muslim community, especially religious leaders, deplored her feminism and declared her irreligious and overly Westernized, even though she remained a practicing Muslim and dedicated her life to helping Indian women. But she also inspired a younger generation of activists, who used works like The Secluded Ones to campaign for women’s rights, and her activism and writing helped to change public attitudes toward women’s education. Shortly after her death at the age of fifty-two, her school for girls started receiving government funding. It still exists in Kolkata today, evidence of Hossain’s work and lasting effect on Indian education. And her influence continues to spread—though Hossain’s crucial contributions to feminism are still not that well known outside of South Asia, “Sultana’s Dream” is increasingly included in Anglophone literary anthologies. In 2018, it was also the subject of an art exhibit by South Asian American feminist artist Chitra Ganesh, “Her Garden, a Mirror,” that illuminated how eloquently and urgently Hossain’s utopian visions continue to speak to the crises and injustices of the present.

Because it could be labeled both utopian literature and sci-fi, “Sultana’s Dream” is perhaps best described as speculative fiction, an umbrella category that includes these genres as well as horror and fantasy. Speculative fiction encompasses any form of imaginative literature with nonrealistic elements: objects, situations, places, or beings that have never existed in the past, and don’t exist in the present, but—in the case of much sci-fi and utopian and dystopian fiction—could potentially exist in the future. Margaret Atwood, for example, uses the term to describe her dystopian novels, such as A Handmaid’s Tale, because they present worlds that might emerge out of present-day political conditions. But the term has also been used more broadly to describe fiction, like that of H. P. Lovecraft, that is nonmimetic but also nonpredictive. While some critics argue that this definition is too broad to be helpful as a description of a literary genre, speculative fiction as a label for a wide variety of works has emerged more prominently in recent years, partly because nonmimetic genres have proliferated and partly because it captures the way that the genres encompassed by it tend to intersect and overlap, particularly in the work of contemporary writers of color like Octavia Butler.

The sci-fi elements of ‘Sultana’s Dream’—electric flying cars, the use of science to harness the power of rain and of the sun—are particularly notable for their prescience and innovation.

In “Sultana’s Dream,” the protagonist, a Muslim woman living in contemporary India, falls asleep and wakes up in a transformed future world: a utopia in which women are free to explore the world at will and pursue an education. Their society is peaceful and just, run by a queen who uses scientific principles to put an end to war, conquer disease, harvest clean energy from the sun, and live in harmony with nature. The sci-fi elements of “Sultana’s Dream”—electric flying cars, the use of science to harness the power of rain and of the sun—are particularly notable for their prescience and innovation. Hossain draws on other genres as well, namely satire and parody, to accentuate her critique of purdah. If satire works through poking fun at its object in order to lambast it, parody imitates the form of its object of critique but incorporates a key difference that indicates why the object is worthy of ridicule. The parody of “Sultana’s Dream” operates by replicating the conditions of purdah in Sultana’s utopia but reversing the gender roles, so that men, rather than women, must stay indoors and take care of the home and the children, while women run society and roam the streets happily, free from harassment and exploitation. The unlikeliness of male seclusion is part of the story’s humor, but this detail also draws its strength from the logic of purdah; if women need to be covered and cloistered because of their own weakness and because of male desire, as supporters of purdah believe, then this desire and male strength (or physical aggression) is the problem that needs to be contained. To the degree that the story seems to hold a low opinion of men—who are held responsible for the prior woes of the world and, more comically, are depicted as lazy and hapless—it does so by leveraging and rearranging real-world assumptions about gender.

More pronounced than its sci-fi or satiric elements, though, is the story’s utopianism, and the way it uses those elements as building blocks. The utopian tradition spans most of literary history; it has been traced back to Plato’s Republic (375 BC) and Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), among other influential texts, and has long been an occasion for feminist imaginings. Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) builds an imaginary city of famous women (both real and fictional) in order to advocate, as Hossain does, for female education. Millenium Hall (1778) by Sarah Scott is also similar to both “Sultana’s Dream” and Padmarag in its vision of female community as crucial to the advancement of both the self and society.

Influential theorists of utopia, such as Ernst Bloch (see Suggestions for Further Reading), argue that utopian thought is a key component of human aspiration. Since the word “utopia” means “no place,” utopias are not necessarily meant to be direct road maps to social transformation. Instead, they are designed to show us what’s wrong with the current world and ask us to imagine it differently; they strive to startle their readers into the perception of new possibilities. “Sultana’s Dream” does just this in its reversal of gender roles and in its transformation of the world into Ladyland: a safe and joyous space in which women are able to live productive lives and nature and culture are harmonized. If the fact that this vision entails keeping men separate and inside the home is the story’s most unrealistic element, it is also its most poignant in its indictment of both purdah and gender-based violence.

Hossain is careful to wrest the critique of gender roles in India away from Western commentators by showing how British colonialism itself perpetuates oppression.

When is the time of utopia? Generally, both utopias and dystopias are associated with the future; “Sultana’s Dream” seems like futuristic sci-fi because of its visionary space-age details. But according to the Queen of Ladyland, her country exists alongside India, which she refers to as “your country” when addressing Sultana. Sultana’s dream world, then, is a parallel world; one that might be accessed, the story suggests, via female education, since this is the key reform the Queen instituted that allowed for the radical transformation of society. Hossain’s novella Padmarag is similarly utopian in its depiction of female community; the institution at the center of the story, Tarini Bhavan, functions as a home for widows, a school for girls, and also as a “Home for the Ailing and Needy.” It welcomes women of all ages, ethnicities, and religions and supports them equally, giving them the opportunity to become self-sufficient by supplying work training or allowing them to work on the premises. By forming a collective, the women free themselves from the need for support from husbands or family: entities that the story often depicts as selfish, abusive, or uncaring. The intentional community of Tarini Bhavan, on the other hand, is one of mutual care and sustenance, both material and emotional. The utopian component of the story, then, inheres in the overcoming of differences between women and the success of their enterprise, but there are also many realistic elements to the story. Rather than occurring in “no place,” Padmarag seems to be set in contemporary India, and the depiction of the school and ancillary institutions that make up Tarini Bhavan clearly draw on Hossain’s experiences running both her own school and the Bengali Muslim Women’s Association (such as the letters of complaint from parents that Tarini reads out loud to her friends in chapter 19). If in “Sultana’s Dream” the utopian Ladyland contrasts with the imperfect state of contemporary India for women, in Padmarag, Tarini Bhavan is a small island of utopian community within a real world of grossly unfair gender disparities. As we learn the stories of the different women that live there, we also learn of the different forms of exploitation and bondage to which women can be subject.

Yet Hossain is careful to wrest the critique of gender roles in India away from Western commentators by showing how British colonialism itself perpetuates oppression. Helen, the British member of the Tarini Bhavan community, demonstrates that women in Britain are subject to similar forms of discrimination, while one of the central villains of the story is a British indigo planter whose greedy machinations lead the heroine Siddika (aka Padmarag) to Tarini Bhavan to join the other women who are seeking refuge from patriarchy there. At the end of the story, Siddika foils both the romance plot that would have her reconcile with her true love, Latif, and a utopian ending, by leaving both Latif and Tarini Bhavan behind to return to seclusion in her hometown. Her motivations, beyond a sense of duty and a desire to determine her own destiny, are not adequately explained, but the story as a whole seems determined to flout expectations of both genre and gender in order to show us both a deeply flawed world and people struggling to carve out a better one. As one of its inhabitants puts it, Tarini Bhavan exists to redress the injustices of the society it inhabits: “Come, all you abandoned, destitute, neglected, helpless, oppressed women—come together. Then we will declare war on society! And Tarini Bhavan will serve as our fortress.” Seemingly disarming in their innovation and humor, both the utopian stories collected in this edition are formidable as well, presenting themselves to the reader as mental fortresses against pernicious gender ideologies and other conventional ideas.

From Sultana’s Dream and Padmarag by Rokeya Hossain and translated by Barnita Bagchi, published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Introduction and suggestions for further reading copyright © 2022 by Tanya Agathocleous.