Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

Most designers would give anything for the staying power that Issey Miyake had. The designer, who passed away at 84, straddled the worlds of avant-garde innovation and mass appeal comfortably, becoming known for his pleated separates as well as his hit Bao Bao bag, with its easily identifiable futuristic shape.

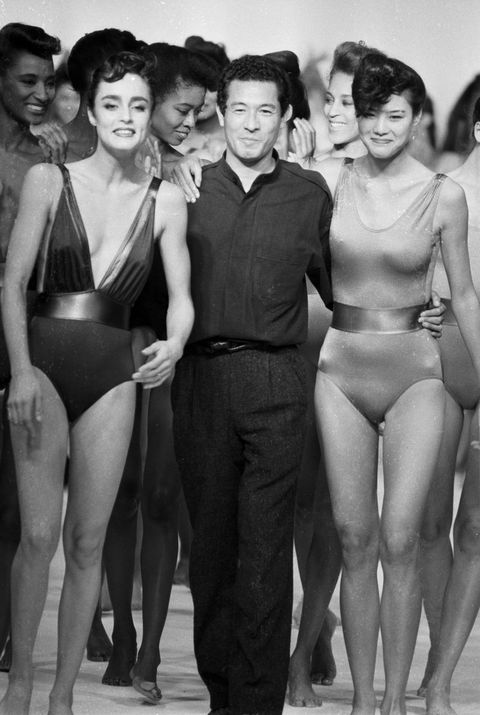

After launching his studio in 1970, the Japan-born designer became a mad scientist of clothes, treating the atelier as his own personal laboratory, or toyshop. He brought a sense of fun to his craft, whether it was a half-filled balloon worn as a hat, headpieces that resembled slices of cheese, or a group of models connected by a single piece of red fabric, while his shows featured playful elements like exuberant dance performances or flying saucer-shaped balloons floating above the models’ heads.

Even when fashion was at its most dour and sour, Miyake’s profound sense of joy transcended the passing moods of the moment. His unwavering embrace of the ultimate uncool emotion, happiness, might have been informed by trauma: he witnessed and survived the bombing of Hiroshima as a seven-year-old. Like many people who’ve lived through harrowing world-historical events, Miyake committed himself to making the world a more positive place, writing in a New York Times op-ed that he “preferr[ed] to think of things that can be created, not destroyed, and that bring beauty and joy.” And he helped put Japanese fashion on the map, making his Paris Fashion Week debut in 1973. His designs ended up on the September cover of that year’s ELLE France.

Miyake’s sense of experimentation led him to push the boundaries of what clothing could be, but never in a way that felt relegated to a museum. Despite his commitment to avant-gardism, the designer never lost sight of the fact that his clothes were far from static sculptures: they were made to be worn, not displayed. “Wearable” has become a favored backhanded compliment of fashion critics, but his clothes really were that, in the best way. His pieces were size-inclusive and gender-fluid before either term was in common currency. His A-POC line (an acronym for A Piece of Cloth), established in 1997, anticipated the zero-waste movement, allowing customers to cut their own pre-shaped pieces from a tube of fabric.

“Anything that’s ‘in fashion’ goes out of style too quickly. I don’t make fashion. I make clothes.”

—Issey Miyake

His cerebral, yet practical, approach brought him acolytes from well outside the fashion world. In fact, a fellow innovator, Steve Jobs, turned his custom Issey Miyake turtlenecks into a daily signature. (Jobs once told his biographer Walter Isaacson, “I have enough to last for the rest of my life.”) The late architect Zaha Hadid treated Miyake’s designs as a canvas, painting on the surfaces of the pieces. And his collections were a staple throughout the art world.

Miyake’s fragrance empire also made him a household name. His first perfume, L’eau d’Issey, released in 1992, was a water-based fragrance that served as an antidote to the heavy, floral scents of the ’80s and became an instant hit, leading to 107 more perfumes. Much like his fashion collections, the bottle design reflected a love of structure and simplicity, with a curved conical column inspired by the reflection of the moon behind the Eiffel Tower at Miyake’s Paris apartment.

Miyake will probably be best remembered for doing more for the pleat than anyone since Fortuny. His Pleats Please line of delicately folded pieces, introduced in 1993, has been irresistible to everyone from Joni Mitchell and Rihanna to Doja Cat and Solange Knowles. (The corresponding menswear line, Homme Plissé Issey Miyake, has attracted fans like Russell Westbrook and Antwaun Sargent.) The comfortable, genderless silhouettes were undeniably ahead of their time, and thanks to a heat-treating system he developed, the pleated pieces were a breeze to wash, travel with, and maintain.

Vintage Miyake is one of those labels that still has relevance no matter what the season; donning it, as Mary-Kate Olsen did at the 2013 CFDA Awards, became an insider flex of massive proportions. But it never became an annoyingly “It” label; instead, it’s one of the closest things fashion has to a perennial. As the designer himself once said, “Anything that’s ‘in fashion’ goes out of style too quickly. I don’t make fashion. I make clothes.”

Additional reporting by Kathleen Hou.