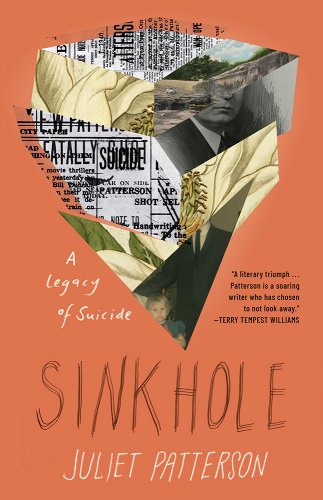

When my father died by suicide in 2008, I was unexpectedly flung into a personal investigation of his death, and also of the legacy of suicide within my ancestral line. His marked the third suicide in my immediate family: both of my grandfathers had also died by their own hand, a truth that my parents rarely discussed when I was growing up. I knew little about these men as a consequence—after my father died, I felt compelled to learn more. But how to do it? And where to begin? As I began writing material for what would eventually become my memoir, Sinkhole: A Legacy of Suicide, I found myself puzzling over how to craft a narrative from such a fragmented family history.

I came to nonfiction after years of writing poetry, and as a writer driven primarily by image and sound, I wasn’t an intuitive storyteller. To conceive of the book, I had to rely almost entirely on my intuition, which meant allowing myself to stray from the limited scope of my family’s story. Place became an important anchor for the book, and with it, research into the history of a single region of southeastern Kansas that came to stand for some part of our family inheritance. To think through the narrative structure, I looked for inspiration in other books that were inventive and genre-bending.

The list of books below are titles I read before, during, and after the completion of my own memoir. I think of them as companions. These books uniquely tackle the subject of ancestral legacy, leading readers into social and historical questions as one way of understanding the personal past. In trying to understand the suicides within my family and the phenomenon of suicide itself, I found myself trying to understand these deaths inside a social sphere. What might they reveal about our American present and past? As a reader, I looked for books that could be, as Maude Newton puts it, “of service somehow, not an inquiry limited to my own family, but one that might interest other readers struggling to reckon with family patterns that seemed to have a power in their lives they couldn’t understand.”

Ancestor Trouble by Maude Newton

A wide-ranging investigation into ancestry and family, Ancestor Trouble places Maud Newton’s own obsessive research of her genetic line alongside broader philosophical, spiritual, and biological questions of inheritance. Structured in seven thematic sections, Newton places chapters about funeral rites and rituals, eugenics and epigenetics, and the history of genealogy itself alongside her family’s story. As Newton’s investigation unfolds, she discovers dark truths about her ancestors’ roles in slavery and genocide, and examines her place in that history. While Newton attempts to reckon with the blood kin of her past—and in particular, with her racist father—by the end of the book she makes clear that other relationships (with chosen family and friends; with the land) are more integral to her sense of self, offering a spiritual turn to this smart and deeply engaging book.

The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom

Sarah M. Broom’s The Yellow House is an ambitious and far-reaching memoir layered with the political and racial history of New Orleans, the natural disaster of Hurricane Katrina, and her large family over half a century. The story revolves around a house in a neglected neighborhood of New Orleans East, a home that serves as both a material artifact and metaphor for the book’s larger discussions of class and race, and as a repository for Broom’s own personal hauntings. Told in three movements that unfold with increasing tension and speed, The Yellow House is both social eulogy and a wry and loving testimony of one family’s life. Broom’s keen observations and eye for detail have rightly earned this book high acclaim.

Bearwallow by Jeremy B. Jones

In his debut memoir, Jeremy Jones returns to a place in the Blue Ridge Mountains where his family settled 200 years before in a personal search to understand kinship with place. Combining history, myth, and family lore, Jones tells the story of generations, layering personal, geological, and political histories to create a complex portrait of a region that’s often reduced to crude stereotypes. Anchored by voice and poetic language, Jones manages to weave his story of self-discovery into the setting of Appalachia (and Bearwallow Mountain) in highly lyrical ways. His work inspired me to trust my own instincts in a historical section of my book wherein I dig into the history of Pittsburg, Kansas—my family’s ancestral home. I wanted readers to feel a sort of wonderment in my work, in the details of a landscape now troubled with the threat of sinkholes, the metaphor from which my book spins. I wanted them to feel what I felt reading Bearwallow.

Interrogation Room by Jennifer Kwon Dobbs

A haunting exploration of a transnational adoptee’s fractured identity, Jennifer Kwon Dobbs’ powerful second book uses a number of approaches (collage, lyric meditation, essay, and erasure) to narrate the search for her birth mother across borders of the Korean peninsula. Prose poems, letters, and redacted documents frame Dobbs’ imaginative exploration, which is driven by a need to confront the geopolitical histories of the unending Korean War, and heal wounds left open by the absence of personal history. As a fan of autofiction and hybrid projects, I appreciate Dobbs’ deft attention to language and image, the blend of intellect and emotion in her storytelling, and the gaps and fissures she invites into her narrative. Readers interested in genre experiments will especially enjoy these elements.

Lose Your Mother by Saidiya Hartman

Interweaving research and personal narrative, Lose Your Mother traces Saidiya Hartman’s journey through Ghana as she researches the slave trade. The book details her explorations of present-day sites along the slave route with precise and evocative detail, drawing on history to offer a gruesome account of slavery’s brutal methods and long-lasting trauma. In detailing this history, Hartman also explores the story of her own ancestors—or what little is known to her—reminding readers of the genealogical ruins that three centuries of enslavement leave behind. A beautifully written memoir that reads like a good novel, Lose Your Mother is an unforgettable book .

Evidence of V by Sheila O’Connor

Novelist Sheila O’Connor combines fiction with history in telling the story of her maternal grandmother, a teenage singer in 1930s Minneapolis who was given a six-year sentence at the Minnesota Home School for Girls for “immorality.” Told in fragments of historical records, diary entries, poetry, and lyric prose, O’Connor’s portrait of her grandmother also illuminates the painful legacy of incarceration through multiple generations. O’Connor’s writing tends toward brevity; here, the spareness of her narrative works to further expose the deep connections between family and national histories—what’s said is just as important as what’s not said, a dictum I held close in the drafting of Sinkhole.

Bad Indians by Deborah A. Miranda

Deborah A. Miranda, an enrolled member of the Ohlone Costanoan Esselen Nation of California, traces her roots in the California Mission. She identifies the motivation for writing her book as to confront the “mission myth” of California, one the author learned early. “All my life,” Miranda writes, “I have heard only one story about California Indians: godless, dirty, stupid, primitive, ugly, passive, drunken, immoral, lazy, weak-willed people who might make good workers if properly trained and motivated. What kind of story is that to grow up with?” Miranda rewrites the myth through oral history, meshing the voices of her grandparents and great-grandparents, tribal history and personal memory with poetry, essay, and visual elements (photography and illustrations). Bad Indians is wrenching in its descriptions of generational trauma, but in Miranda’s writing, readers will find a way through the darkness and be reminded of the way language can shape and reclaim the past.

Open Midnight by Brooke Williams

Conservationist Brooke Williams unearths the story of his great-great grandfather William Williams, who traveled with a group of Mormons across the wilderness to Utah and died one week short of arrival. At the onset of the book, the writer realizes he has little more than a short list of facts to work with. However, as he sets out to map wilderness regions of the Utah desert, he creates evocative imagined scenes of his ancestor, who serves as a spiritual guide through the book’s arc. Drawing on Jungian psychology to explain the transformative effects ancestral relationships can have on our psyches, Williams contends that the future “survives on creativity and imagination and integration.” This book renders Utah’s Red Rock Desert, and the expansive territory of the writer’s mind, with a unique passion that will resonate with readers.