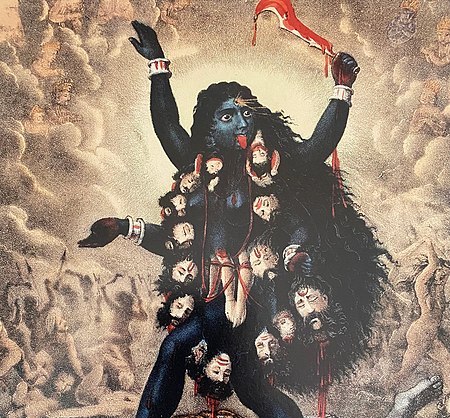

Nivedita, a mixed-race graduate student in Dusseldorf, has it (kind of) figured out. She runs a popular online blog about being a mixed-race German woman and has a staunch support system in her cousin Priti and an ok boyfriend. Most importantly, she studies with Saraswati—a hot, hotshot, woman-of-color professor who teaches her everything she needs to know about postcolonial studies. Saraswati is the glamorous professor we all dream of studying with, the type who “stare[s] straight at the camera lens, her lips pursed like she was about to blow a kiss, as if she’d just said Foucault.” But Saraswati turns out to be white, not South Asian. Identitti, translated from German by Alta L. Price, follows the chaotic unraveling after Saraswati is outed, complete with unexpected alliances, cultural theory rabbit holes, and goddess hallucinations.

Sanyal, who received a PhD in cultural history and is the author of two academic books (Vulva and Rape), is an expert at upending assumptions about race or identity politics. Weaving in Twitter replies, blog posts, and childhood memories amidst the Saraswati chaos, Identitti is a hilarious and polyphonic roller-coaster ride.

It was a joy to connect with Mithu Sanyal over Zoom, where we talked about the German language for ethnic identities, collaboration within social media platforms, and writing about the mixed-race German experience.

Jaeyeon Yoo: What is this novel about for you?

Mithu Sanyal: Everybody always thinks it’s a book about cultural appropriation, and it’s actually a book about being mixed race. I needed the cultural appropriation story as a catalyst to tell the story of being mixed race. My first draft was just Nivedita and Priti, and their relationship. I was kind of running in circles, but once there was this thing on the outside (of the Saraswati case), it was so easy to tell the story. In Germany, we just haven’t got any literature about being mixed race or post-migrational literature. Rather, of course we have it, but not in the mainstream.

In Germany, we had this law that you could only become German if you were of German blood, if you had a German father, originally. When I was born, I couldn’t get German citizenship because my mum had a German passport but my father did not. My mum was one of the feminists who fought for the right to give their children their nationality. The idea was that being German was something inherent, and that these [non-German] people go away again, these people don’t exist.

When I was born, I couldn’t get German citizenship because my mum had a German passport but my father did not.

In the last twenty years, we’ve changed the laws about nationality and how you can get a German passport—you can get one by being born, and by living here, what else? But the idea that these [mixed race narratives] are German stories, they’re just as much our stories as well: that didn’t exist for such a long time. When I was writing the novel, I found out that Thomas Mann [a canonical German author] is mixed race as well. His mum is from Brazil, but nobody tells you; so, he is seen as this incredibly white German guy. But in all his novels, he writes about it—for example, his father gets the mum from “the bottom of the map.” Thomas’s brother Heinrich, he wrote a story called “Between the Races” about his mother. It’s a novel in plain view, but you’re not taught it. Being misled is a part of Germany’s history, but also of German literature, and we don’t see it immediately. It’s like: what you don’t know, you can’t see.

JY: Given this context, I found it fascinating in that you make us question our assumptions about what “mixed race” even means, especially the “race” part. What was it like, to write a work that was so self-reflexive—constantly deconstructing these concepts that it focuses on?

MS: Right now, everybody is talking about identity politics. But when I was writing the novel in Germany, that was a year or two before, it was just one of those terms nobody used. It was like taking something really dusty. In a way, this gave me a freedom because I was not so afraid about any backlash. It was still quite a cozy niche to write, and asking those questions [about identity politics] were easy because I wasn’t afraid of being canceled or anything back then. And that has changed, really has changed. But by now, I’ve got a kind of a name that people don’t think I’m just [writing Identitti] as a subterfuge to get rid of these discussions. Because I really think the discussions about cultural appropriation are incredibly important. Even with my nonfiction books, the themes were always part of a left wing or feminist or anti-racist group. But, at the same time, it is incredibly important for me to challenge our own assumptions. Not from the outside, not saying “Oh, aren’t you crazy? Stop doing what you’re doing.” From the inside, because I believe if we want to do what we’re doing better, we’ve got to constantly question ourselves.

I’m genuinely interested in how the book is going to be received [by Anglophone readers]. I’m not condemning Saraswati: that is the whole point. That until the end you stay unsure where you want to jump. I do know people who have read the novel and really hated her, but I also know people who read the novel and really loved her. And that’s important to me. I really didn’t want to judge her.

JY: Thinking more about the Anglophone reception: Identitti so effectively pointed out how race doesn’t work the same way globally, yet so much of the global language around critical race theory is English. Do you have more to say about the role of English in contemporary racial identity formation?

MS: In Germany, we didn’t speak about race at all after the Second World War. We basically had this idea, “This is what the Nazis did, and I’m not going to touch the subject.” Even the word “race” in German, Rasse, has never undergone this change; in the English language, “race” now means a sociological construct. It doesn’t mean that everybody who uses it knows or means that, but it is a part of the word. If you say Rasse, it just refers to the biological elements. And, sure, there are different human races, of course. So, we’ve had this big debate, because it’s in our constitution that nobody should be discriminated against because of gender, et cetera, and Rasse. But if you take [the term Rasse] down, then you’ve got a problem: you’ve got to pinpoint it. What can you put in instead? It’s really difficult because when you say racism, then you’ve got to prove intent—prove legal injustice in legal terms.

There is a lot of bad sex in German literature, not often good sex. I wanted to have at least one orgasm in a book, just because life isn’t like that—without orgasms or sex

Anyways, we didn’t speak about [race in Germany]. Even in the ‘90s when I wanted to speak about race, people said, “Yeah, but there are no human races, so there can’t be any racism.” And that was the end of the conversation. If I want to talk about it, then I’m racist, because I’m referring to racial constructs like the Nazis. So, you didn’t have a language at all. Then we imported the English language. It was very liberating. With a word like race, we could speak about things. Saying POC was liberating—but POC doesn’t mean the same in Germany. For example, quite a lot of people from Eastern Europe came in the ‘60s and ‘70s. They were called guest workers and so [many conditions] that apply to POCs in America absolutely applied to them, but in America, they would be considered white. I was on a podium once, and the American activist said that there are not enough POCs. But although we were all POC on the podium, she couldn’t recognize us as such because of the cultural differences. [For another example,] in England, I’m Asian—but in Germany, Asian doesn’t mean people from India. It only means people from Eastern Asia and people from Southeast Asia. Even those words don’t overlap. When I was born, the term for people like me was foreigner [Ausländer]. Which is bullshit, because I was born in Germany. I’m not a foreigner. We didn’t have a word for it; we didn’t have the idea that you could be brown and German. It just didn’t exist.

JY: What you’ve just said and some of the passages in Identitti have me questioning: do you think we need to express ourselves through language, in order for identity to exist at all? Put differently: do we need to “narrativize” ourselves, in order to “be” any identity?

MS: I’m not sure whether I’ve got the ultimate answer to that, but I know that I need narratives. When I grew up, I didn’t have a language for people like me. I always had to invent the language and the narrative for myself. Now there’s a lot of language about it, but it also means that we draw new borders. I’m glad that we’re starting the conversations I would like us to have as a society, but to do so in a more loving and friendly way. I’m so glad we can talk about these experiences, but now the experiences have become identities. Being mixed race is part of my experiences, but is it really an identity? Yeah, sure. It is, in a way, but what is an identity? We are starting to have new divisions but, at the same time, it is so nice to not to have explain yourself completely—which is like a burden being taken away. John McWhorter says in The Language Hoax that we overestimate the value of language, that it can’t really change that much. I agree to a certain extent: we’ve got to change laws and realities and working realities and all this—not just with language, to do something. What my job as a novelist is that I create narrative. I create stories. I’m trying to help change laws, but I haven’t been very successful. I have been quite successful in creating stories, and I always think that we need both narratives: the narrative of what’s special about certain groups, but also the narrative about what we all share as humans.

I also thought Identitti also really probed at our ideas of desire: what we find attractive, what we find erotic. I wonder if you see this theme being in conversation with your other books [which focus on depictions of vulva and rape]?

MS: Definitely. Sexuality is an integral part of life. And it’s so weird that it doesn’t play the same role in literature very often, especially in German literature. There is a lot of bad sex in German literature, not often good sex. I wanted to have at least one orgasm in a book, just because life isn’t like that—without orgasms or sex—and also because that’s the kind of person that Nivedita is. She’s young; she’s an intellectual but she receives the world very much through her body. So, it was important that this aspect was in the narrative. For readings, I’ve noticed I usually read the one scene where she finds Saraswati’s speed vibrator and masturbates. I also like the idea of [emphasizing] masturbation because I still hear people say, “Oh, women don’t masturbate.” The scene also shows their relationship, because there is a lot of crossing of borders that Saraswati does. On the other hand, it was very important that they never had sex with each other and have some borders that were not crossed.

JY: I loved how you solicited your friends for essays on a (fictional) scenario within the book. I made a mental note—if I want to include smart writing, coax my friends to write smart insights for me! I wondered if you could speak more about the role of collaboration in your writing?

MS: I don’t believe in the idea that we as authors are writing a novel on our own. I’ve been trying to write this novel for years and years now, and it never worked because the discussion, the discourse wasn’t that around. The internet was one of the characters in the book, and I can’t write the internet. It’s this many-headed monster in a way or a great choir. So, I just thought, “I’ll ask people and then I don’t have to write it. This is brilliant.” And it was initially the other way around. Because the book hadn’t been written, they didn’t understand me at first, [asking,] “So you want me to tweet about something that hasn’t happened?” So then, how can I log on to the internet in the book? Basically, all these two-liners [of fictional internet] took me an hour on the telephone or longer to explain. But after I started getting the ball rolling, I wanted to do loads of different things. I wanted to have all these different voices, and also to test: would this be an issue in Germany?

So, I asked them to write in the way they would write without thinking much about it—how would you react to it emotionally, at night, if you just read it quickly? Then I started asking people I didn’t know or my friends I knew via the internet. And that was so amazing. Very many people just donated tweets to the book, even though they didn’t know me personally—they knew of me from the internet or from my books and articles. This trust in me, that was so lovely and added new things; the tweets enhance the reading experience. Some of them are incredibly funny! I couldn’t have written that—not just the content, but also the style. They’re all written in their own way. The first reviews on Amazon, for example, people were saying, “Mithu is so good at mimicking the words and recognizing the way people write on the internet.” But obviously I wasn’t mimicking them, they’d written them.

JY: Do you have other thoughts you’d like to share about Identitti?

MS: I hope it will be different with the English translation than how it was received in Germany. Basically, the book has been received as autobiographical here, which is weird. This really is a novel. I don’t write autofiction, although I do appreciate it, and it’s a different genre. If people expect autofiction, they will be disappointed. And who am I? I mean, I’m not twenty-five. I’m basically Saraswati’s age, but I’m definitely not a white professor passing as a POC, so who do you want me to be?

JY: At least in the US, I’ve found that—generally speaking—if someone is not white and/or marginalized in some manner, then writes about that issue, people are going to automatically assume that it’s autofiction. It sounds like German audiences had a similar reaction to your book.

MS: Absolutely. I think there’s still this idea that being white equals being universal. That if you tell a white story, it’s a universal story; if you’re marked in any way, then you’re talking about yourself. When I started reading, all the books I was reading were about people who are really not like me, so I was bridging that gap and that was good. But then, when I read the Buddha of Suburbia for the first time—even though it’s such a different book from my life—it was like reading yourself for the first time and thinking, “This is so close to me.” And that was a relief. I think we need to do both in reading and in any other intellectual endeavor: we need to find ourselves and we also need to understand how others project themselves into the world. Once you understand and learn from yourself, it is a lot easier to look at the world.