This essay, by Logan Hoffman-Smith, is the third in Electric Literature’s new limited essay series, Both/And, which centers the voices of trans and gender nonconforming writers of color. For the next thirteen weeks, on Thursday, EL will publish an installment of Both/And, with the series running through spring and into Pride Month. At a time when my community (the trans community) is a political target for the far-right, I am incredibly proud to have the opportunity to elevate the voices of those most marginalized—and most often silenced—in our community so that we can tell our own stories. Both/And is the first series of its kind, and you’re in for a treat: stories of invisibility and hypervisibility, sexy stories, dreams and love and grief. But what ties them together is the fearlessness and honesty with which they are told. And the volume—because when it comes to our lives, it’s time our voices be the loudest in the conversation.

—Denne Michele Norris, Editor-in-Chief

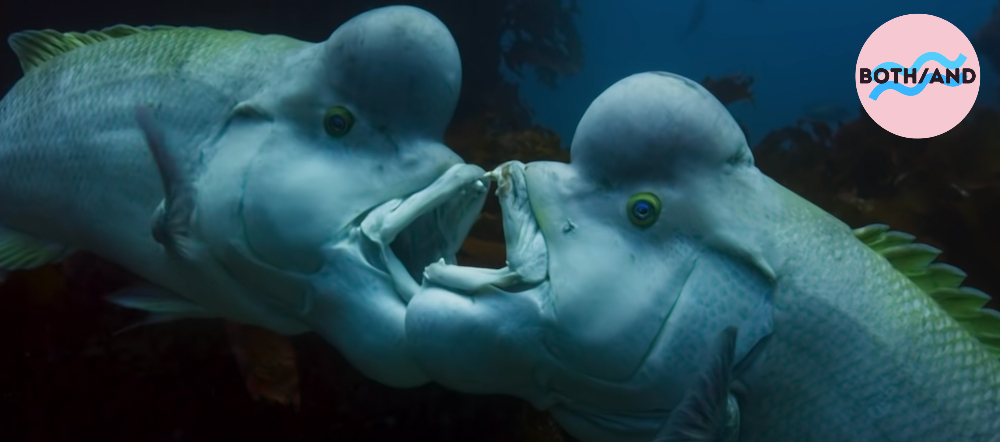

If you dive across the rocky shores of the Korean Peninsula, you may find a shy, hump-headed fish staring back at you. The Kobudai, also known as the Asian Sheepshead Wrasse, is a thick, large-jawed fish that can shift gender based upon its needs and, hopefully, how it feels on a given day. The average Kobudai will live as an estrogen-based fish during its early years but transition to a testosterone-based body once it is older and larger. Not all of these fish transition, but they all have access to free hormones if they want to, without any concern for health insurance, because they are fish. As I plan for my own second puberty, videos of divers with Kobudai comfort me.

Perhaps the most well-known Kobudai video was published in June of 2017 by Great Big Story and documents the relationship between Hiroyuki Arakawa, a scuba diver, and Yoriko, an Asian Sheepshead Wrasse. It’s early morning and the waters of Tateyama, Japan are calm, a cool, deep blue. Each wave carries the taste of sea vegetation, of iron and salt. Arakawa and his team take a small motorboat out several miles from the shoreline, and when they stop, Arakawa, clad in his black diving suit, tastes the air on his tongue and jumps in.

It was only when the construct of gender was superimposed onto my being that I felt dysphoric.

I was born in 1996, which makes me of the Pokemon Emerald generation, and grew up abroad as a Chinese American adoptee in Tokyo and Singapore. These formative years were texturized by an unutterable but nonetheless embodied feeling of loss–of boyhood, of homeland, of language, of the texture and smell of my biological parents. Though I never had words for how I felt, was bereft of any notion that life outside of girlhood was possible, I felt truly as if I wanted to live a life outside gender. Whenever I was set free to roam outside, to sift through sand or comb through the tall grass for rare beetles, I felt embodied most fully in myself. Each of my actions brought joy and carried resonance beyond categorical life. It was only when the construct of gender was superimposed onto my being that I felt dysphoric. Like when I was eight, for example, and coming home in my cargo shorts full of BBs from the park near my house, I ran into a disheveled, professorly British man in a Barbour jacket outside of my apartment complex.

“Say, kid. Do you know the password?” he asked. He adjusted his briefcase on his shoulder and cocked his head towards the electronic doorman where we punched in our lobby access codes.

I told him I wasn’t supposed to give the code out.

“Good lad.” He punched in his door code and ruffled my squid-like bowl cut into a silly mess. I felt a rush of pleasure at the man’s assumption of my boyness, but also a wrongness, as if I’d gotten away with something not quite true. Still, for years, I remember coming back to this memory and holding it to my ear like a seashell, as if a portal within myself to a place of deeper resonance, one I could feel but never name.

It wasn’t until my sophomore year of high school that I obtained access to the language of transness, albeit in a time when the word was whispered dangerously around nooks and corridors, an unwelcome intrusion into the liberal, cishet mechanics of the all-girls boarding school I attended. For months, a white day student in my year had been embroiled in negotiations with school administration regarding his use of he/him pronouns and outspoken acceptance of his transness, a notion the school seemed to worry would destabilize the cishet tenets of gender they’d structured their business around. If this day student would simply use she/her pronouns and revoke his “claims of being trans” until graduation, the school would sweep the whole situation under the rug. How easy it was for them to ask him to delegitimize himself, to attempt to steal his language like some sort of deranged pronoun Ursula, as if that would change anything within us trans-students-in-hiding. As if there hadn’t been some refrain, even before I had language for it gaping through me all that time, some searing knowledge of difference, here, here.

Now, I imagine my two selves—older and younger—meeting knee-deep in a muddy creek, my older self a refracted mirror.

It’s interesting to think about how directly the microcosm of my boarding school mirrors modern anti-trans discourse in the United States. Through abundant anti-trans legislature, especially regarding trans-affirming praxes in schools, sports, and, in the case of Greg Abbott, even within the home, the United States government believes that trans people will cease to exist if pushed out of public spaces, if they are refused live-giving medical care via gender-affirming surgeries and hormones. Simultaneously, through the creation of new anti-trans campaigns and media, these claims circulate a reductive, ideological chokehold on what transness is. Through the lens of empire, transness is only able to be seen as in opposition to cis identity–a deviation both dialectically tethered to, and defined by, its negative. It is therefore ideally constrained by dominant structures, absorbed into systems of domination rather than allowing an alternate way of being.

Arakawa and Yoriko are very good friends. You can tell because Yoriko swims right up to him and sometimes even requests a kiss on her lumpy head. Cute!!! She lives at a depth of 56 feet next to a red, underwater Tori gate built by human friends. Coral is abundant in her domain–purple Bubble Coral and orange Elkhorn–where she has lived and spent time with Arakawa for 30 years. Arakawa mentions that one day, a few years ago, he noticed Yoriko was moving slowly, lethargically, unable to catch her own food, and so he fed her five crabs every day for about 10 days. That’s 50 loving crab meals!!! He notes that now, after this act of tenderness and care, she’s feeling a lot better.

I think of friends who I’ve lost due to systemic violence, friends who should have been allowed to thrive.

70 percent of our planet is covered by the ocean, which contains 97 percent of all the world’s water. One might think this could mean that the Kobudai has endless spots to scope out and enjoy, but as trash, chemicals, and global warming increasingly threaten our global marine environment, the Kobudai are left with fewer and fewer places to go. Rising ocean temperatures and rising acidification levels have caused mass coral bleaching and lower oxygen levels within the water for the ocean’s billions of creatures. Within the past few months, the Bering Sea’s shift from an arctic state to a sub-arctic state has caused a mass migration of billions of snow crabs towards colder waters. Additionally, shifts in PH levels can cause mass death for sea life, as well as toxic algae blooms that cut off large swaths of sea from the sun. Fish like the Kobudai rely on coral and crustaceans for food and shelter–once one of these elements is threatened, all of them are. While it is unknown if Kobudai populations are low enough to technically render them endangered, they are certainly at risk due to the impacts of climate change brought on by global capitalism, and I worry because there is still so much I think we can learn from these fish and their ocean friends: about gender, about symbiosis, about what it means to be a living thing.

Like other aspects of identity, transness is clearly influenced by its intersections. Even when talk of transness was omnipresent at my boarding school, transness was implicitly framed as a white identity group by community members. Examples of trans people were tall, lanky white trans guys who dominated Youtube and search engines. Though I’d always felt uncomfortable with my gender as a formerly unathletic femme Chinese American, I was genuinely convinced I couldn’t be trans. It reminds me of the time I didn’t think I could be both Asian and a lesbian until I watched Pretty Little Liars, which was revolutionary in the way it portrayed a romantic relationship between Emily Fields and Maya St. Germain, two femmes of color in different phases of outness. I still watch those Youtube compilations all the time! While silly when I think about it now, I also was unable to conceptualize myself as trans until I enrolled in undergraduate school and met other trans people of color for the first time. Oh, I thought. Well, duh. A few years later, though, after joking with my peers, I heard a few of them say, quietly, me neither. I didn’t know I could be both trans and a person of color too.

I am resistant to categorizing the experience of transness as “natural” or “unnatural” and using the Kobudai’s experience as evidence for either simply because I don’t think it’s a useful organizing principle, nor do I particularly care. Systemic notions of what is “natural” are constantly in flux and codified to the benefit of oppressors, police, and lawmakers–by this, I mean that “unnatural” is a weaponized blanket label given to those who the state is intent on controlling and/or erasing from public life. If my being is unnatural, so be it . I am too busy living each day as a person who is soooooo stylish and cute.

What I do find interesting about the Kobudai’s experience of transness is that the species’ experience as a testosterone-based fish is informed by its experience of girlhood. Kobudai will only transition once they’ve reached a certain size and use their larger bodies to protect younger Kobudai. Girlhood, care, and transition are inherent parts of their identity, and learning this tickled me in a butch way. Knowing this has texturized my own memories of my girlhood with feelings of bravery, and purpose–mended the gaping hole of longing within me for a stolen boyhood. This has been a big theme in my life: finding wholeness through reimaging loss. Now, I imagine my two selves—older and younger—meeting knee-deep in a muddy creek, my older self a refracted mirror. I give thanks. Our memory smells like springtime. We orbit each other like a frog and tadpole, like changing seasons, like ghosts.

The other day, I was scrolling through my friends’ Instagram stories–because I self-ID as wizened and don’t use Tiktok–to find that Iowa had enacted a transgender bathroom ban and a ban on gender-affirming care for minors. Though I feel like this is the product of long-time lobbying, I still feel gutted about the anti-trans laws sweeping our country, the unprecedented escalation to codify “unnatural others” through legislative attacks on bodily autonomy. I think of friends who I’ve lost due to systemic violence, friends who should have been allowed to thrive. “We take care of us” has been a trans resistance slogan for a long time, and this was the message my Post-Apocalyptic Fiction Writing class passed around to each other that day. I dwell on these two words often, what it means to feed a sick friend of a different species five crabs a day, to serve as cover for younger and more vulnerable members of trans community, to take care.

Right now, I’m looking for an outfit to wear to a “rave” at Dave’s Foxhead Tavern. I’ll probably Facetime my friends to see if any of my fits make sense. On my birthday last year, my very best friends here in Iowa threw me an Under the Sea-themed birthday party and I felt very, very loved. Sometimes, being a trans fish means having a great time with queer and trans friends and trying a “designer drug that is somewhat like ketamine” together, and dancing, and tonight I will think of Hiroyuki and Yoriko and all the versions of myself who I had to swim through to feel alive like this, at this exact moment, with so much love, and I will think of all of my courageous, brilliant friends, all of us diving under the fog lights, all of us now and here, here, here.