Unlike the narratives created in both literature and film, selling one’s soul usually isn’t a literal Faustian bargain. Despite our devilish fantasies, it’s not Al Pacino leaning across a desk, asking us to sign away our innermost being for fame and fortune, scantily clad sylphs gyrating in the background, urging us towards our own temptation. While Faustian bargains certainly exist in the everyday world, they are generally much more subtle in nature.

I have always been fascinated with the darker side of things., I consumed Anne Rice’s entire oeuvre at fifteen, then wandered the streets under the full moon, desperately hoping a vampire might appear in a dark alley to bestow “the dark gift,” as Rice puts it, with one sharp kiss. Throughout my life, I’ve routinely been called “intense,” “driven,” or “obsessive.” Many people might take offense to these descriptors, but the Scorpio rising in me positively swoons. Any person, place or activity that could be described as “too intense” or “too much” has always had a visceral pull. If I were asked to sell my soul to Lucifer himself, I’d probably scramble for a pen—just to see what might happen next. Like TikTok famous confidence guru Serena Kerrigan, I have always been a big proponent of doing things, “for the plot.” Of course, this has gotten me into my fair share of trouble of over the years—until I learned to assign the more dangerous arcs to my characters instead of enacting them in my own life.

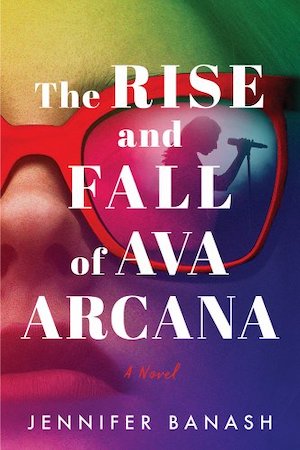

My new novel, The Rise and Fall of Ava Arcana, explores the heights and pitfalls of fame through the story of two women, both destined for pop stardom. The irrepressible Lexi Mayhem, who will stop at nothing to reach the top, and Ava Petrova, whose loyalty to Lexi—and her own talent—may cost her not only her soul, but her very life itself. Here are 7 books about losing your way on the climb to the top, where the pursuit of fame and power beyond your wildest dreams may be the ultimate devil’s bargain.

Beauty by Brian D’Amato

Welcome to the not-so-distant future, where human faces can be sculpted like putty by the right pair of gifted hands. A modern-day Frankenstein that interrogates our cultural obsession with beauty and youth, D’Amato depicts the glamorous and seedy world of Manhattan in the ’90s from the POV of Jamie Angelo, a marginally successful painter whose side hustle is performing amateur plastic surgery on the elite in his downtown loft. But when Jamie decides to “create” a celebrity, using his girlfriend Jaishree (whom he renames Minaz) as his muse, and becoming a surgical Svengali in the process, he descends down a rabbit hole of depravity and soullessness, turning Jaishree into not only a cultural icon, but a literal monster.

Look at Me by Jennifer Egan

I have always been fascinated by celebrity, but even more so by imposters. Growing up, I devoured all of Highsmith’s Ripley books like candy. Egan’s Look at Me is, in my opinion, an overlooked masterpiece, light-years ahead of its time in prefiguring our current obsession with influencer culture. Egan’s novel is the story of two Charlottes: Charlotte Swenson, a model, who after a horrific car wreck, is left with eighty titanium screws in her face, and her namesake, the daughter of her best friend from high school, a precocious suburban teen coming of age in small town Illinois. Although the surgery model Charlotte endures after the crash succeeds in restoring her former beauty, she is now weirdly unrecognizable, a veritable stranger in the glamorous world she once occupied so seamlessly. Eventually, she becomes involved with an Internet start-up seeking to monetize the lives of both “Ordinary” and “Extraordinary” people, and her alter-ego becomes a viral sensation for viewers to obsess over, watching and cataloging her every move. The novel explores how and why identities shift throughout the course of a life, and how one’s teenage years are a catalyst for the person we will one day become. But most of all, it serves as a warning of the very real dangers of constructing an identity for the sole purpose of mass consumption.

The Vampire Lestat by Anne Rice

Full disclosure: I am team Lestat. Yes, I empathize with a callous monster. But who could blame me when he’s so charming, so depraved, so . . . terrible. Rice’s lush prose, like winding a long, velvet scarf around an exposed throat, invites the reader into a dimly lit world of decadence and decay. A snapshot of the glittering, demonic 1980s, campy as hell and the sexiest of all the Lestat novels, Rice explores what happens after the devil’s bargain has been made. Throughout the narrative, Lestat embarks on a kind of vision quest, interrogating his identity and origins (well, as much as any rock star vampire with a god complex the size of a Buick can), and through his music, catapults himself to world-wide fame. But ultimately, even from a self-proclaimed monster, sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll is no real panacea for the emptiness that lies within.

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

Wilde’s masterwork must’ve weighed heavily on her mind when Anne Rice created the character of Lestat, a manipulative charmer with the emotional depth of a puddle. No doubt that if Gray had managed to escape Victorian London and time traveled to the 21st century, he likely would’ve become a model or influencer—or perhaps even a rock star like Lestat. Sadly, he remains confined to the lavishly furnished, stuffy drawing rooms of salons, falling in love with one pretty face after another and bleeding them dry. Gray, a social vampire, is only ever loyal to his own beauty. But his rapidly aging portrait in a hidden room keeps the score, turning more repulsive with every misdeed, though Dorian’s visage stays as youthful and unblemished as ever. And in the portrait’s odious face, Gray must confront his own lack of morality, the horror of his truest and most hideous self.

Sign Here by Claudia Lux

Everyone likes to complain that their job is hell, but for Peyote Trip, it’s a literal fact. Peyote works in the deals department on the fifth floor of Hell, where the coffee machine has been broken for a century. It’s a decent gig, but Peyote has set his sights higher, and getting the last member of the wealthy Harrison family to sell his soul just might be Peyote’s ticket to upward mobility, his one shot to climb the corporate ladder right to the very top. Lux’s darkly comic novel gleefully skewers corporate America, asking how much of your soul you’d be willing to sell for a leg up.

Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner

An aging spinster, wanting to escape her tyrannical family, runs away to the forest to become a witch. Published in 1926, Warner’s novel is a precursor to the work of later surrealist writers such as Angela Carter and Jeanette Winterson, and subversive and feminist as anything penned by Virginia Woolf.

Lolly takes a room in a hamlet called Great Mop, which she realizes later is inhabited entirely by witches, and adopts a feral black kitten as her familiar. But freedom comes at a price, especially for women, and so when Lolly’s nephew, Titus, tracks her down, imploring her to return home, it is only the devil himself who can grant Lolly the freedom she desires most. At the novel’s close she has a vision of the women “all over England, all over Europe . . . as common as blackberries, and as unregarded,” to which he has offered the lure of adventure, “the dangerous black night to stretch your wings in.”

Flicker by Theodore Roszak

Long before Night Film was even a glimmer in the eye of Marisha Pessl, there was Flicker, a 600-page love letter to the golden age of Hollywood and the secret history of the movies. Roszak’s epic novel depicts Jonathan Gates, a grad student in Los Angeles who becomes obsessed with the work of Max Castle, a legendary director of the silent screen who went on to make some of the creepiest horror flicks imaginable before disappearing from the public eye at the very height of his notoriety. Gates’ quest to find out what happened to Castle—and his lost film archive—takes him on a wild ride through the underbelly of Hollywood and into the heart of darkness itself. An homage to and exploration of midnight movies, X-rated skin flicks, and underground cinema, Flicker serves as a cautionary tale, a reminder that immersing yourself in the someone else’s story—at the expense of your own—might lead you down the darkest of paths, one from which there is no return.