And these things,

that live by going away, know that you praise them; fleeting,

they look to us for rescue, us, the most fleeting of all.

Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Ninth Elegy”

The author of twenty-five novels and short stories, Dominique Fabre is a student of philosophy, a photographer, globetrotter, and high school teacher who leads writing workshops in hospital settings, tries his hand at poetry, and has been a member of the jury of the Prix du Jeune Écrivain (Young Writer’s Prize) since 2013. He has received thus far the Prix Louis Barthou (2003), the Prix du Jeune Écrivain (2013) for Mon Quartier, Icare et autres nouvelles, the Prix Eugène Dabit for the populist novel (2014) for Photos volées, and the Prix Maurice-Genevoix from l’Académie française (2015) for L’Inspiration de son œuvre. These four prizes are sponsored by foundations that support works of general literature, populist literature, and literature recognizing humane and moral values. Three of his novels are available in English. The Waitress Was New (Archipelago, 2008) and Guys Like Me (New Vessel Press, 2015) represent the part of his work that is deeply anchored in Parisian culture and gives new life to the roman populiste through his ability, according to a review in Elle magazine, to act as a “discreet megaphone of the man in the crowd.”

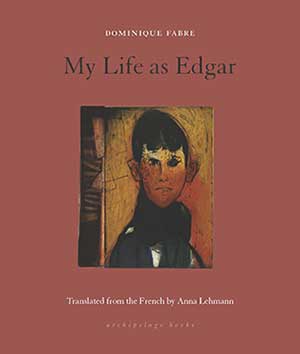

My Life as Edgar was Fabre’s second novel in French (Le Serpent à plumes, 1998), and its English edition, translated by Anna Lehmann, is the newest one (Archipelago Books, 2023). These two dates, albeit unintentionally, underscore the cyclical nature of this unhurried and steady French novelist. While an in-depth comparison of the three translations is not the purview of this article, the three professionals who have translated one novel each must be mentioned here: Jordan Stump, a leading American translator of innovative French contemporary literature (Chevillard, Redonnet, NDiaye, Volodine); Howard Curtis, a seasoned British translator who worked with Simenon and translates from French, Italian, and Spanish; and Anna Lehmann, an American freelance translator specializing in Patrick Modiano and Yvan Pommaux. Each translator has perfectly rendered Fabre’s “tonalities” and the twists and turns of discrete plots interspersed with monologues. While it is not unusual to see several translators try their hand at one author, the steady recurrence of Fabre’s translations over the past fifteen years is an important indicator. It shows the necessity to write a thorough introduction to a body of work that has quietly grown immense with the years.

My Life as Edgar was Fabre’s second novel in French (Le Serpent à plumes, 1998), and its English edition, translated by Anna Lehmann, is the newest one (Archipelago Books, 2023). These two dates, albeit unintentionally, underscore the cyclical nature of this unhurried and steady French novelist. While an in-depth comparison of the three translations is not the purview of this article, the three professionals who have translated one novel each must be mentioned here: Jordan Stump, a leading American translator of innovative French contemporary literature (Chevillard, Redonnet, NDiaye, Volodine); Howard Curtis, a seasoned British translator who worked with Simenon and translates from French, Italian, and Spanish; and Anna Lehmann, an American freelance translator specializing in Patrick Modiano and Yvan Pommaux. Each translator has perfectly rendered Fabre’s “tonalities” and the twists and turns of discrete plots interspersed with monologues. While it is not unusual to see several translators try their hand at one author, the steady recurrence of Fabre’s translations over the past fifteen years is an important indicator. It shows the necessity to write a thorough introduction to a body of work that has quietly grown immense with the years.

Populist novels are present in American literature even though they are not recognized as such. Fabre, who spent time in the United States in the 1980s, has affinities with John Cheever, John Fante, Bernard Malamud, and Alan Sillitoe. Among his favorite authors are Willa Cather, Charles Bukowski, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose The Crack Up he cites numerous times in Guys Like Me. He is also heir to the French populist literature that began a century ago with Eugène Dabit’s 1929 Hôtel du Nord and its eponymous movie directed by Marcel Carné. Jean-Paul Sartre, Henri Troyat, and Jules Romains also flirted with this genre; Henri Calet, Emmanuel Bove, Raymond Guérin, and Louis Guilloux championed it in the 1930s and ’40s. The genre climaxed with François Truffaut’s 1959 movie Les 400 coups but was soon eclipsed by the Nouveau Roman, whose extreme deconstructionism and stylistic experimentation appealed to the baby boomer generation. Populist novels stayed too far away from trendy theories and great adventures to be glamorous. Their insistence on giving voice to ordinary urban and working-class people without varnish or flourish, their oft autobiographical stories, created truthful and sincere depictions of a reality most people wanted to escape from.

Writing “organically” developing novels, Fabre has given new life to this genre. Even the titles of his works indicate everyday concerns: “I too shall go far in life,” “Waiting for lights out,” “I would like to see Callaghan again,” or “I want to go home.” His characters, much like the author himself, grow up in the 1960s, enter adulthood in the 1980s, and reach middle age with a cell phone in hand, ordinary men and women whom he wants to save from oblivion. He commits to memory their fluid urban fabric, namely the encounter between traditional French craftsmen and working-class residents of the northeast of Paris and immigrants from French, British, Spanish, and Portuguese colonies. Older residents are evicted, immigrants open new shops in remodeled urban quarters, and French colloquialisms coexist with polyglot dialect and slang. The scrupulous chronicle of this triple architectural, linguistic, and demographic kaleidoscope trains the reader’s attention on the inevitable displacements of ordinary people.

Fabre’s scrupulous chronicle of this triple architectural, linguistic, and demographic kaleidoscope trains the reader’s attention on the inevitable displacements of ordinary people.

Characters who emigrate from the colonies are in motion too, along with their language. Fabre relinquishes his narrator’s voice to feature a delectable assortment of quaint colloquialisms and popular phrases, his voice and vocabulary changing with characters, in order to build a more authentic story. In two of the three stories of Trois Passagers, we find multilingual and multicultural characters seeing the West from outside, relating the weight of postcolonial dilemmas, trying to escape poverty. The first story, “Histoire de Luis,” is a decidedly nonlinear “confession” by an immigrant woman from Santo Domingo. The second story, “Vietnamienne,” features a refugee Vietnamese woman who befriends French men from a dysfunctional family before immigrating to the US. The third story, “Mon père,” is autobiographical; his father’s funeral is a pretext for Fabre to revisit the life that Fabre père spent in the French Maghreb and Senegal before returning to France with a second wife, and to show his solidarity with those who come from displaced and broken backgrounds. The perfect country, just like the perfect father, is unattainable and estranging/estranged. The emptiness and loneliness remain, with the feeling expressed in The Waitress Was New that “life is still on the other side” and encounters with others only touch the surface of things.

In the short story “Histoire de Luis” featured in Trois Passagers, English and Spanish phrases coexist with the broken French of the female character who has come to France at great peril to seek medical help for her daughter, and whose cousin tried unsuccessfully to reach the pays de cocagne (i.e., the United States), experiencing tribulations reminiscent of those depicted by Vladimir Lorchenkov’s eastern Europeans characters in The Good Life Elsewhere. The broken French and American of the Cambodian immigrant in “La Vietnamienne,” also in the same volume, is triumphant. In En passant (vite fait) par la montagne, the broken French interspersed with African and Arabic words of young immigrants enhances the credibility of this real-life adventure during which Fabre was asked to accompany a group of at-risk immigrant youth for a weeklong trek in the Alps organized by the philanthropic association En Passant par la Montagne. These newer, younger, polyglot languages are those of first-generation immigrants in search of a better life, uprooted, in transition linguistically as well as physically.

These newer, younger, polyglot languages are those of first-generation immigrants in search of a better life, uprooted, in transition linguistically as well as physically.

During the twenty-seven years of his writing career, Fabre has loosened traditional narrative structures and blurred boundaries between short stories and novels. His plots follow a loose chronological pattern that allows long stream-of-consciousness monologues. Each of the longer short stories of Trois Passagers could be short novels, and the short stories of J’attends l’extinction des feux constitute a novel of sorts. On the other hand, the chapters of such novels as Aujourd’hui could be short stories. Each chapter or short story becomes a separate tableau, a slice of time dissected with a dizzying substratum of seemingly insignificant thoughts and activities that compose a composite, collective portrait of city life. Often chapters have no title and are designated by numbers, as if they were the acts of a play. Such narrative structure reveals the un-ordinariness of the characters. Observing the world while talking to oneself is not only realistic but meditative—a technique also visible in Wiesław Myśliwski’s meditative A Treatise on Shelling Beans (2006). Also, the epilogues not only readjust the perspective from the microscopic to a bird-eye’s view but continue the characters’ constant motion. They give the ordinary man, in Cyprian Norwid’s words, his metaphysical dimension. They give weight to their lives—the further alienation of the at-risk youth in En passant (vite fait) par la montagne after a week of reprieve spent trekking in the Alps, or one’s legacy after death in Je veux rentrer chez moi—a smile, a way to look, a phrase, traces of ourselves.

Fabre uses high-bourgeois society as a control gauge to contrast their orderly, secure, established, and relatively glamorous lives with those of “in-between” people, characters displaced from the working class but not yet completely secure on their way up the social ladder. While the main novel on that topic is Les soirées chez Mathilde, there are numerous references in other works to bourgeois boarding school classmates, rich men crossing the paths of divorcees, and powerful bosses upon whose ability to escape reality the lower-class characters look wistfully. These displaced persons are mostly male characters and run the entire span of human life, from a child with disabilities and an unloved, ill-fitting, rebellious teenager to a middle-aged man in the throes of midlife, or an almost-retired man contemplating the onset of old age. Their loneliness is accented by the realistic (naturalistic) depiction of their environment and the dysfunctionality of their family relationships.

In Aujourd’hui and in The Waitress Was New, Fabre portrays middle-aged bartenders who fight loneliness by being around other people and not listening too closely while sorting out background noise and interaction. Such reality made of a myriad of unimportant and unnecessary details is experienced as “a bunch of movies running at the same time,” according to Aujourd’hui’s bartender Pierre, or as a kind of stew “that we all do when we talk to ourselves,” as Fabre told his translator Howard Curtis. The personal thoughts that interrupt these settings serve as counterpoints which highlight the characters’ loneliness. Thus, serving the wheat with the chaff, Fabre opposes the classical admonition to cut meaningless details out. His technique plunges the reader most effectively in the mixture of reality and daydreaming that is “the paradise of the poor,” the depressed, and the aimless. More importantly, however, remembering odd things delays oblivion. These thoughts in perpetual and repetitive motion create the kind of tightly knit ambience that makes a lasting impact on the reader.

The characters’ displacement is highlighted by the space in which they move, a space punctuated by bars, train stations, trains, cars, roads. Travel is omnipresent, including walking; at the center of this perpetual travel is the Heraclitan Seine River. Fabre’s Butorian, meticulous descriptions of places and travels put his characters in perpetual motion, and he confesses that he “needs to inscribe his story into geographies that talk to him.” From Place de Clichy to Asnières, from St. Lazare train station to the Alps, travel is almost ritualistic. It provides these excursions with neutral, anonymous places that give the illusion of freedom. Although there are important anchors in this world, such as apartments, the favored stops of Fabre’s characters are public places such as restaurants and especially bars—the home of the homeless, familiar, warm cocoons. Described in real time, these travels become inner monologues, serving as reality-anchoring and anxiety-exorcising. They create a pendulum movement between the external environment’s myriad of details and the digressions/rhizomes of inner thought. This dizzying diversity soon becomes familiar to the reader who feels the characters’ marginality and aimlessness and recognizes their quixotic quest for ideal happiness that drowns in daily disappointment.

Fabre’s ability to change registers extends to the more traditional language of the Parisian world of families who first grafted themselves onto its culture, then grew deep roots in its urban and suburban landscapes. The more traditional colloquial street French is found in novels such as Aujourd’hui, in the volume of short stories J’attends l’extinction des feux, and in Guys Like Me and The Waitress Was New. These works exude a substratum of longue durée, a whiff of graciously aging twentieth-century culture that hangs on tenaciously to its island community which the outside world is ready to scatter. Such linguistic agility and broad knowledge show that the narrator is first and foremost an attentive and skilled listener.

Fabre’s works exude a substratum of longue durée, a whiff of graciously aging twentieth-century culture that hangs on tenaciously to its island community which the outside world is ready to scatter.

Friendships are lifesaving and give meaning to their lives. They are formed in boarding school and mature with the main characters, surviving separations and silence. Two novels—J’aimerais revoir Callaghan (2010) and Je veux rentrer chez moi (2019)—are particularly complementary as they take friendships from adolescence to middle age and follow and contrast the characters, one a more timid adolescent who keeps within the job-assigned responsibilities, and the other a daredevil who grows up carrying his entire life’s possessions in a suitcase or a trunk. At the onset of their friendship, both protagonists are living “outside” the norm. Unloved and rejected by his family, unable to bond with his parents, Callaghan becomes a drifter who reunites serendipitously with his friend, a white-collar worker who is dulled by routine. Richard, the protagonist of Je veux rentrer chez moi, had loving parents and a stable home but was caught in the drug and booze culture of the 1980s and lived in an alternate reality of nighttime parties, insomnia, and impromptu visits to his friends, returning to the real world long enough to have a child and teach for a few years.

Both Callaghan and Richard disappear, puncturing the friendship cocoon that had protected the narrator and his friends. The description of Richard’s death, however, is a first attempt by Fabre to focus his powers of observation on the phenomenology of death. Confined to a hospital bed by lung cancer, unable to breathe or talk, Richard returns home by looking into hospital visitors’ eyes—his last travel. This pavane for a dying friend links the minute physicality of the last days of life to the normal daily comings and goings of staff and visitors. Here too, reality is made up of disconnected, hermetic worlds that authority figures pass through, whether a boarding school priest, a hospital staff member, or family and friends. The narrator’s memories are part dream, part reality, mirroring the in-and-out of consciousness of the dying friend’s unending agony. The high school jargon returns thickly, and the narrator’s flashbacks parallel Richard’s regression into death. “Home” no longer has a lasting or precise location and becomes a web of train stations, bars, travels, and the living spaces of family members. These two novels indeed weave a broad and solid tapestry.

My Life as Edgar represents Fabre’s foray into childhood and the world of unwanted, unloved, abandoned children from birth into adolescence, a plight that was particularly dire in postwar France. Providing a window into this timeless issue is quite arresting, especially since Fabre sees, hears, and speaks with a child’s voice. A sort of savant, somewhat developmentally disabled but clairvoyant, Edgar spends the first years of his life with his divorced mother, then is sent to a foster family in Savoie. His ears have a phenomenal ability to pick up all kinds of noises: birds in the trees, moles underground, unspoken thoughts of his mother, and hushed conversations about him between adults. He knows without knowing that he is not “quite all there” but makes the most of being outside normal relationships. Sensitive, innocent, and wise, he has an unusual sense of humor that shows the inverted world in which he lives. While in Savoie, he notices one day that the water’s edge near a dam is marked with a warning sign that says “No Drowning Here”—the interdiction to die, rather than the interdiction to have fun. When he is recalled to Paris and enters boarding school, Edgar stops hearing things but continues to escape from reality with a new group of friends.

Fabre moves from the first-person narrative to the third person. Edgar is “I” and “he” in yet another mark of dispossession of self, of disconnection, but also of perspective and affirmation. One day, on his way to yet another routine weekend at home, Edgar decides to run away, but, being Edgar, he is quickly brought to the police station. There is no sign of rebellion in him during the final scene where he awaits his mother—Les 400 coups ending in a whimper, childhood assassinated. Selflessness and innocence cry out against a deaf world, underscoring the paradoxical nature of separation, just as in one of Fabre’s recent poems:

Knotted lights

night butterflies

Lie against the waves

then rise up

in the middle of a street

where you’ve never been

in a city whose name is yet unknown to you

one that feels unfamiliar

the one where I was born

tiptoed away

the one where I’ll die

obscures my eyes and ears

Enter a pub

whether Rome or Paris

Lyon or Turin

and sit down

nod to your neighbors

not knowing why you are here

(and they wouldn’t either?)

[translation my own]

The daily grind meets the metaphysical in instants that become eternal without fanfare.

Emotions always appear as watermarks in Fabre’s work. They are easily identifiable through precise descriptions, but their depth may be overlooked by a reader too quick to turn the page. These watermarks, this absence of avowed sentiment, reflect the condition of ordinary people who are usually restrained, have propriety, and keep to themselves. The imprint of this absence indicates an existing space for a dialogue between the characters’ inner world and their external context. This gives a poetic touch to Fabre’s work and, more than anything, humanizes the world of ordinary people, strangers/friends who oscillate between yearning for home and aspiring to travel and discover the world without losing one’s ability to be amazed by the world or to lose the noblest human quality—sincerity. The daily grind meets the metaphysical in instants that become eternal without fanfare. Fabre’s tale of blue- and white-collar French people’s everyday lives and of Parisian neighborhoods at the turn of the new millennium is in fact a parable that carries an important message: saving language and culture from oblivion is one important way to repair the world.

University of Tennessee at Martin

Bibliography

Moi aussi un jour j’irai loin, 1995

Ma vie d’Edgar, 1998

Celui qui n’est pas là, 1999

Fantômes, 2001

Mon quartier, 2002

Pour une femme de son âge, 2003

La serveuse était nouvelle, 2005

Le Perron, 2006

Les types comme moi, 2007

J’attends l’extinction des feux, 2008

Les prochaines vacances, 2008

Avant les monstres, 2009

J’aimerais revoir Callaghan, 2010

Il faudrait s’arracher le cœur, 2012

Des nuages et des tours, 2013

Photos volées, 2014

Je t’emmènerai danser chez Lavorel, 2014

La mallette / Quand on a des blessures, les pas sont plus lents / Choses qui, 2014

En passant (vite fait) par la montagne, 2015

Les soirées chez Mathilde, 2017

Les enveloppes transparentes, 2018

Le grand détour, 2018

Je veux rentrer chez moi, 2019

Aujourd’hui, 2021

Une enfance, 2021

Trois passagers, 2022