WASHINGTON — The U.S. Space Force is reviewing bids from satellite manufacturers competing to produce and integrate experiments for the Space Test Program.

Vendors could be selected as early as December for the Space Test Experiments Platform (STEP) 2.0., Lt. Col. Jonathan Shea, head of the DoD Space Test Program at the Space Systems Command, said May 8 during a conference call with reporters.

The STP office last week issued a revised draft request for proposals for the STEP 2.0 contract and is seeking comments from vendors by May 19.

The plan is to procure “commercially developed spacecraft with demonstrated flight heritage to host DoD-sponsored payloads over the next 10 years,” he said. STEP 2.0 will be an indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) contract.

Vendors picked for the IDIQ will compete for orders that will include building a spacecraft, integrate payloads with launch vehicles and provide ground support for on-orbit operations.

The first task order to be awarded will be for STP Sat-8, a 12U cubesat projected to launch in 2025.

Shea said the STEP 2.0 program is looking to take advantage of lower-cost commercial buses, especially ESPA-class rings, to bundle as many smallsat experiments as possible into a single platform.

“With STEP 2.0, the idea is that we’re going to try to buy what we can and not have to modify,” he said. “We want to get as many folks who have proven flight demonstration on buses into a kind of a consortium that we’re able to leverage.”

Col. Joseph Roth, director of innovation and prototyping at the Space Systems Command, said he expects several commercial bus manufacturers to compete under the IDIQ.

Northrop Grumman makes the Long Duration Propulsive ESPA or LDPE, which the Space Force used to deploy experiments. “But there are other manufacturers that are trying to get into the ring market,” said Roth. “Any fully qualified bus that has actually flown in the space environment for 365 days can compete for the STEP 2.0 contract, whether it’s Northrop Grumman, Millennium Space, Blue Canyon Technologies, any of the bus providers that have on-orbit heritage.”

Shea said the STP program is seeing a large demand from agencies that are building experiments and need help getting them to orbit. This year, at least 60 candidate experiments — a mix of government, academia and private industry projects — are being considered by the DoD space experiments review board.

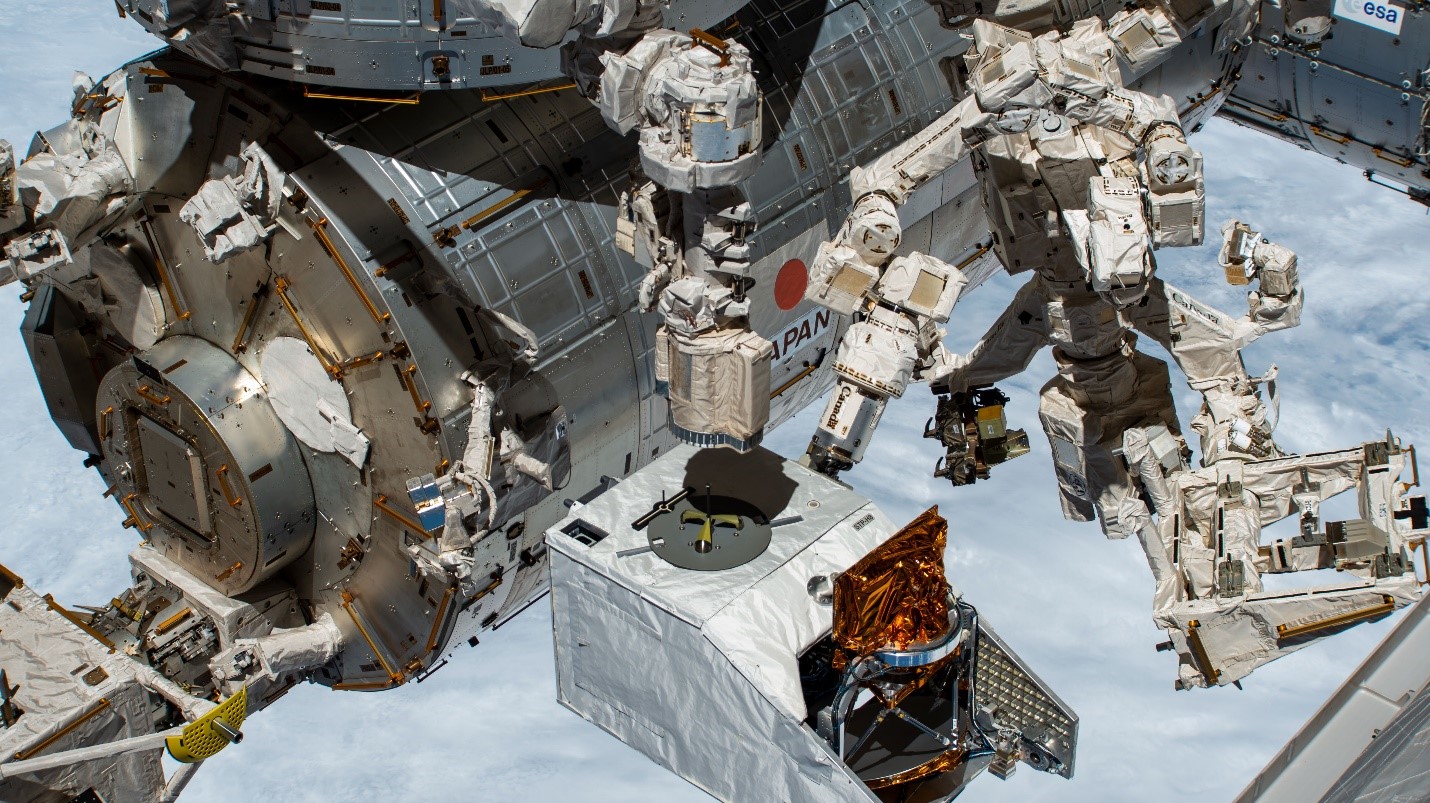

STP relies heavily on ISS

The STP program, established in 1965, on average has sent to orbit 10 to 15 experiments a year and is heavily dependent on NASA to deploy payloads from the International Space Station.

The STP program also relies on the Space Force’s National Security Space Launch program to fly experiments as rideshares on NSSL missions. It also uses the Space Force small launch program that awards STP missions under an multi-vendor contract known as OSP-4.

With more experiments seeking rides and limited funding, “we look for someone who’s just got some excess capacity we can use and we will start playing matchmaker,” said Shea.

Shea said he sees increasing interest in cislunar space experiments and hopes to team up with NASA’s Artemis program to coordinate opportunities.

NASA’s Johnson Space Center and the ISS program office “do the majority of the heavy lifting so a lot of our experiments can get a subsidized ride to the ISS,” he said. This is much less costly than getting experiments into space through other means.

The majority of experiments today are flown either from the ISS or on SpaceX Transporter rideshares, said Shea. If the ISS ceases to operate as projected in 2030, that could be “pretty existential” for future STP experiments.

“Anything that wants to go around 400 kilometers circular, we got a great deal for you,” he added. “When you start talking about more exquisite orbits, like sun-synchronous orbits, higher low Earth orbits, highly elliptical orbits, or especially geostationary or cislunar, “then those opportunities start to decrease dramatically for STP.”