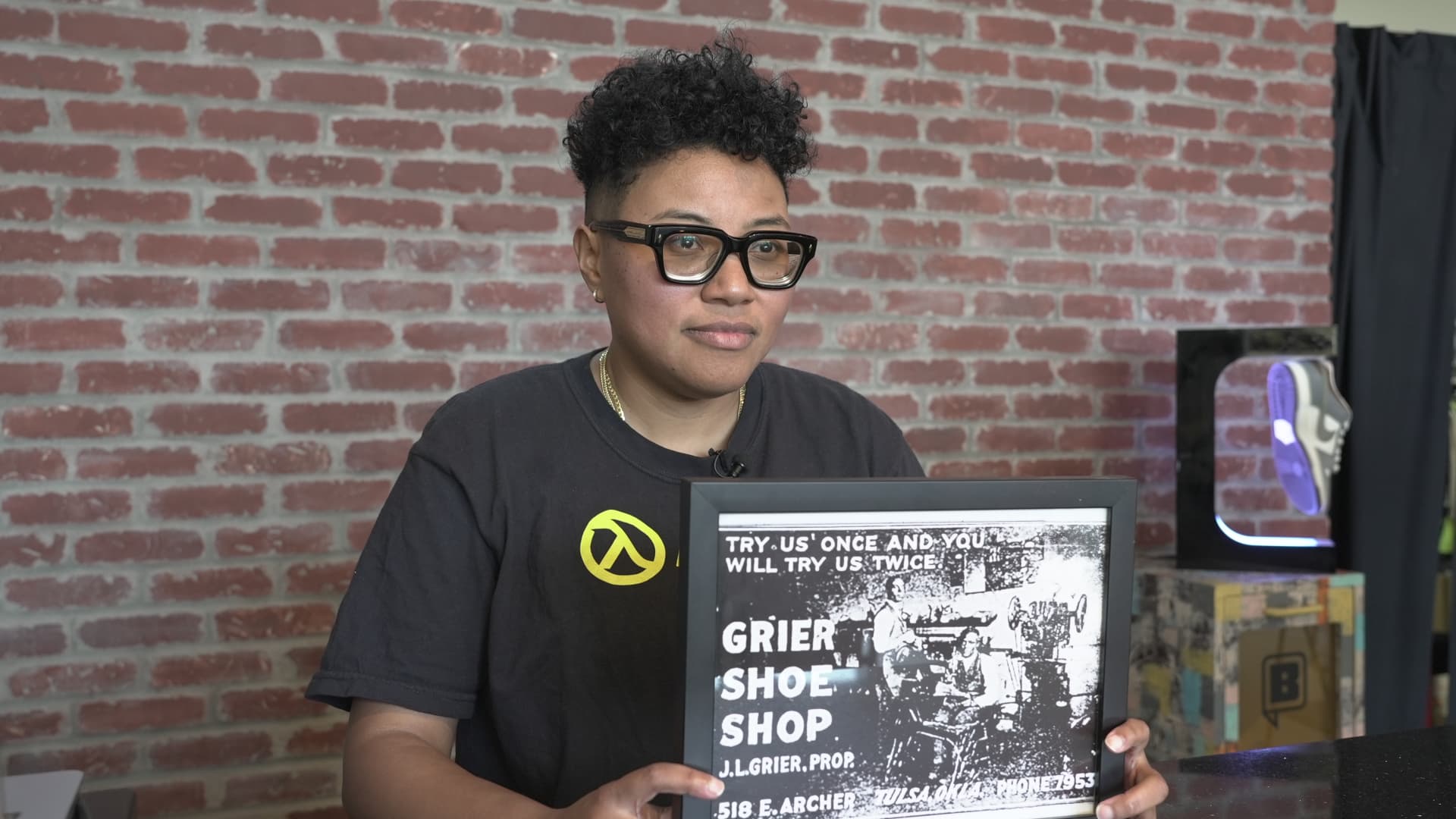

Venita Cooper, founder of Silhouette Sneakers & Art in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Parnia Mazhar| NBC News.

TULSA — Nestled among rows of colorful shoes lining the walls of Silhouette Sneakers & Art, a framed black-and-white photo reminds owner Venita Cooper of the giants whose shoulders she stands on.

Overlaid on that picture is the company name, Grier Shoe Shop, and its address — which is part of an area known as Black Wall Street. It was the business occupying Cooper’s building before it was destroyed during the Tulsa Race Massacre more than a century ago.

In the decades between Grier and Silhouette, there have been many waves of Black entrepreneurship in the area, said local advocates. They’ve been particularly enthused by the focus on innovation and technology in the latest renaissance, which was turbocharged after 2020’s racial reckoning galvanized corporate and social interest in uplifting Black Americans.

“We’re trying to revitalize the space, build successful businesses down here — and take back what was taken from us,” Cooper said in an interview.

Cooper also runs an artificial intelligence platform for the shoe resale market called Arbit. With these ventures, she’s part of a growing class of Black entrepreneurs tapping into Tulsa’s history for inspiration and resources for support.

She went through Act House, an accelerator program for entrepreneurs of color. The program provides an investment of $70,000 with no interest or equity requirements, and nonlocal participants relocate to Oklahoma’s second-biggest city to collaborate with peers and other professionals.

A difficult history

Bringing participants to Tulsa for several months can help them see how they fit in the bigger picture of minority entrepreneurship, said Act House founder Dominick Ard’is. Some who were not already in the community have stayed beyond the accelerator’s conclusion, adding their burgeoning businesses to the growing ecosystem of minority-owned firms in the area.

Act House is part of a collective of organizations aimed at supporting Black-owned businesses in Tulsa, a mission these stakeholders view as especially salient given the city’s fraught history.

Dominick Ard’is, founder of the Act House accelerator in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Parnia Mazhar| NBC News.

The Greenwood district, as Black Wall Street is more formally known, was attacked by a white mob on May 31, 1921, an event that would later be recognized as one of the worst racial massacres in American history. More than 1,000 businesses and homes were raided and as many as 300 Black people were killed as the mob torched the neighborhood.

That history gained newfound attention after the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and during the massacre’s centennial anniversary in 2021. Outside Tulsa, advocates say that some of the corporate interest in supporting Black businesses has waned in the ensuing years as interest rates and economic uncertainty rose.

But within the local community, groups continue trying to rebuild what was lost by empowering the next generation of entrepreneurs. One way disparate efforts among stakeholders have been centralized to best serve founders is through Build In Tulsa, a network of firms such as accelerators and investors.

Build In Tulsa Managing Director Ashli Sims said she’s seen more recognition of Tulsa as an emerging technology hot spot and a clearer understanding of why it’s important for Black entrepreneurs to go there given the history. Sims, who grew up in the city, said there’s an effort to combat the notion that people should leave to find the success that was once ubiquitous on Black Wall Street.

“I want young, Black kids growing up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to look around and see tech startups, I want them to see CEOs, I want them to see founders, I want them to see innovators,” Sims said. “I want them to see wealth, and I want them to know that that is part of their future.”

For entrepreneurs, Sims said this means showing they don’t need to move to a coastal city to take their venture to the next level.

Shoes displayed on a wall at Silhouette Sneakers & Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Parnia Mazhar| NBC News.

Build In Tulsa recently opened a space for entrepreneurs of color to collaborate and take meetings. The three-floor building sits on the corner of North Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Reconciliation Way, the latter of which was renamed in 2019 after previously honoring someone with alleged ties to the Ku Klux Klan.

That physical community in Tulsa has been paramount for founders such as Edna Martinson, whose company, Boddle, offers three-dimensional games for children that encourage learning. Through Tulsa, the Act House alum now feels part of the national Black entrepreneurship space and finds herself with more connections at popular events for owners such as Art Basel in Miami and South by Southwest in Austin.

“It’s not just like a Tulsa island on its own,” Martinson said. “It’s really like a gateway to the broader national community of founders of color and ecosystem builders.”

Funding challenges

Despite progress, advocates and entrepreneurs are quick to note that the patchwork of organizations offering support doesn’t erase the inequalities faced by Black founders around the country. The biggest obstacle many pointed to is difficulty obtaining funding.

Disparities exist at every stage. A 2016 Stanford study found Black entrepreneurs start with about $500 in outside equity, while their white counterparts have $18,500. Though the dollar amounts are modest for both groups, the National Bureau of Economic Research reported that white-owned startups saw five times more capital from family and other insiders than those owned by Black people did.

Black founders received just 0.48% of venture capital dollars in 2023, according to Crunchbase. And traditional financing measures are hampered with practices such as personal collateral requirements that make it harder for those without generational wealth.

“It is literally exhausting,” said LaTanya White, founder of Concept Creative Group, a firm focused on business development and wealth transferring among Black founders. “All the while, you’re still trying to build a business, you’re still trying to create something that’s going to open doors for generations in your family and in your community.”

Those challenges add to an already dire picture of the state of equality within business. Less than 3% of U.S. businesses were Black owned despite the racial group making up more than 12% of the country’s population, according to the most recent federal data analyzed by CNBC.

Olaoluwa Adesanya is one of those entrepreneurs struggling with funding. While he’s found hesitancy from venture capitalists to invest in hardware-focused technology companies, Adesanya has been able to get financial help from a range of groups focused on founders of color.

In addition to participating in Act House, he’s received tens of thousands of dollars from programs such as AfroTech and a pitch competition for Black founders at Harvard Business School. He also won a grant from a Black Wall Street organization.

Adesanya said both the monetary and communal support in Tulsa was pivotal in bettering PalmPlug, his product for improving hand mobility. Before he came to the accelerator, Adesanya had a prototype that he constantly worried would break. Now, he frequently fetches compliments for its design and quality.

“It’s still very challenging,” said Adesanya, who returned to Seattle but is considering moving to Tulsa permanently. “But I’m also super grateful for the Black community, and how they really helped get us to where we are today.”

There’s also evidence of Black founders having a tougher time winning government grants or contracts, said Grant Warner, director of the Center for Black Entrepreneurship, a collaboration between two historically Black colleges and the Black Economic Alliance Foundation. He said that one of the most obvious instances he’s seen was an identical application for a government award that was only approved after the white person’s name was switched to go before the Black person’s.

‘The dreams of our ancestors’

Entrepreneurship can appear particularly risky to Black people as they try to sustain their families’ financial standings, according to James Lowry, the author of two books about minority wealth. That’s in part because of a reluctance to sacrifice the security prior generations obtained when breaking into corporate America, he said.

Black people don’t always have the same luxury some other racial groups have of seeing models within their communities of people who successfully started their own companies, he said. Still, Lowry said he’s been excited to see more Black students attending business schools and thinking about creating large ventures.

“It’s sort of like getting off to a late start and competing against generations of people who have been entrepreneurs, even within their family,” said Lowry, who’s also a senior advisor on workforce and supply chain diversity at Boston Consulting Group. “It’s a catchup, but we’re making headway.”

The Black Wall Street Mural in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma, on Friday, June 19, 2020. Greenwood, known as Black Wall Street, was one of the most prosperous African-American enclaves in the U.S. before it was burned down by a white mob in 1921.

Christopher Creese | Bloomberg via Getty Images

On the national scale, advocates see the potential for government programs to help level the playing field for founders of color. For instance, the Uplift Act would provide resources to create business incubators on the campuses of historically Black and minority-serving universities, as well as at community colleges. The Minority Business Development Agency’s Capital Readiness Program helps disadvantaged entrepreneurs scale their ventures, but the program got more than 1,000 applications for fewer than 50 spots.

Black entrepreneurs and stakeholders point to resilience as a key quality that helps founders succeed in spite of these unique obstacles. In fact, academic models have found that women and minority founders show higher levels of resilience due to a combination of challenges and support structures.

For Adesanya and others who have come to Tulsa, they can see and feel the refusal to give up in the face of difficulties from those who came before them.

From the sidewalk markers indicating the businesses that stood prior to the massacre, to the museum dedicated to the history of Black Wall Street, reminders of the past have helped these founders better understand where they fit in a long legacy. And it inspires them, they say, to break down barriers for themselves and those who will come next.

“We’re really the dreams of our ancestors,” Adesanya said. “What we’re doing is what they dreamt of and what they suffered for.”

— NBC’s Shaquille Brewster, Parnia Mazhar and Andrew Davis contributed to this report.

Watch more from this story on Hallie Jackson NOW at 5 p.m. ET.

Read the original article here