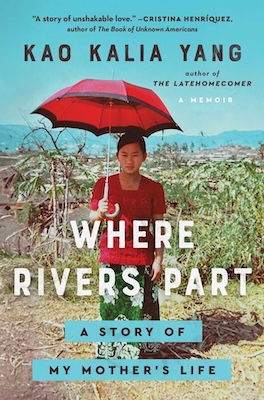

In this most recent memoir, Kao Kalia Yang takes on the voice of her mother, Tswb Muas, to tell the heart-wrenching (or rather “liver-wrenching” if you’re Hmong) story of a woman who made an impossible decision in the jungle of Laos that would shape the rest of her life. Where Rivers Part transports us to the village Dej Tshuam (Where Rivers Meet), where Tswb was born, and introduces us to her family, including her mother, a formidable woman who helps us to understand the kind of woman Tswb would become. Amidst the violence of the Laotian Civil War, we witness Tswb’s family’s flight to the protection of the jungle where, by chance, she crosses paths with the young man who would become her husband. At the age of sixteen, under threat of encroaching Pathet Lao forces, she leaves her family and follows her husband and his family to the refugee camps in Thailand and then to the United States. Each new environment brings new challenges, including hunger, death, and racism, that Tswb confronts with necessary courage but also quiet exhaustion and sometimes unspoken regret.

Tswb Muas’s story, as told in collaboration with her daughter, invites us to explore ideas of motherhood, womanhood, love, longing, home, and survivance in a patriarchal world heavily impacted by war and displacement.

I was born in Thailand, where so many refugees from the wars in Southeast Asia fled and waited and waited and waited to be resettled, including my father’s family. In 1990, when we arrived in the United States, I was five years old. I grew up in rural Northern California loving books, but most of the books I read were about people who didn’t look like me.

Kao Kalia Yang’s Hmong family memoir The Latehomecomer came out in 2008, when I was 21 years old. It was the first book I had ever seen written by a Hmong-American author about the Hmong-American experience. At that time, a part of me shied away from reading it, almost as if I knew I wasn’t ready to face that painful part of our people’s history.

Over the years, it traveled with me through the different phases of my life. Finally, in 2023, I finished The Latehomecomer on a dav hlau (iron eagle: airplane) heading to Portland for an academic conference. While it took me 15 years to finish The Latehomecomer, it took me two weeks to read The Song Poet, Kalia’s memoir about her father, and just a handful of days to read Kalia’s new memoir, Where Rivers Part.

I had the pleasure and honor of interviewing Kalia about some of these themes as well as possible presents and futures for peb hais neeg Hmoob (our Hmong people).

Pa Vue: I would love to start with the title of your memoir, Where Rivers Part. I can think of at least two instances in Hmong history where a river has made a significant impact on our community: first, when our ancestors settled along the Yellow River in what is known today as China; second, when hundreds of thousands of Hmong people had to flee across the Mekong River after the end of the Laotian Civil War. What do rivers mean to you, and how have they impacted your life?

Kao Kalia Yang: Where I was born, Ban Vinai Refugee Camp, the only river I knew was called “Dej Kua Quav”—translated to English, it means “River of Feces”. It wasn’t until I was in graduate school and was in conversation with a medical doctor who had visited the camp the year and month I was born that I learned that the river of my youth was just an open sewage canal. The adults knew it but I didn’t.

The first river that I truly met was the Mississippi River when my family was resettled in St. Paul, MN as refugees of war. As a child, my older sister Dawb and I often begged our father to let us accompany him on fishing trips… where my uncles took their sons. It was along the banks of the mighty Mississippi that I began to learn and connect with the other rivers in the lives of our people, the Hmong: the Yellow River in China and, of course, the Mekong River along Thailand and Laos.

All along the way, I was mystified by stories about the River of Forgetfulness; I was told as a child that when a Hmong person dies they return to the land of the ancestors, and there flows a river. If you drink from it, you forget everything and you can begin anew. My heart would race when I heard stories about the powerful dragons that dwelled in the deepest parts of the rivers of the past, the possibility that there might be dragons even now in the American rivers.

For me, rivers have always been a great mystery, a source of fear, of inspiration, of change and transformation. They speak to me of the places and people that I come from, the flow of history, of life, and of course, of love.

PV: In your prologue, you stated that you wanted to “claim the legacy of the woman” you came from. Can you share what you meant by this?

I was told as a child that when a Hmong person dies they return to the land of the ancestors, and there flows a river.

KKY: Our mothers and their mothers before them are so unknown to the world that we live in, so tremendously neglected by the history books, by the eyes and ears of people—not simply those in positions of power but the individuals they work with, drive alongside on the streets, and even the people whose houses are connected to theirs. I’ve watched generations of Hmong women live the consequences of that unknowing. They are subject to the stereotypes that people govern about who they are—as welfare mothers, as dispensable laborers, as inconsequential to the happenings of a larger society and history. I want to do my part in shedding light on the incredible lives that have enabled our possibility; yes, me in the story of Tswb Muas, but in some sense also other Hmong daughters and their mothers. There are worlds within worlds, hearts brimming with emotions, thoughts sparking whole horizons in the women who love us.

PV: Throughout the memoir I sensed that you were trying to define motherhood through your mother’s eyes, but I also felt that your own insights of motherhood were present. How did your experience of becoming a mother prepare you to write this memoir?

KKY: I knew that I couldn’t write my mother’s story until I experienced the realities of motherhood myself. I simply couldn’t do justice to her story. She is a woman who became a mother at the age of 16 and had her final child at the age of 42. In that span, she gave birth to seven living children and seven dead ones. So much of her life has been devoted to mothering, so I had to tell my impatient heart to hold until I knew what it was like to have a child grow inside of me, to give birth to her, to hold her close to my chest, and to lose a child, too, to reach with shaky hands for a baby the world would never know as mine.

When I came to this book, I had learned some of what it meant to be a mother, to have loved both the living and the dead. This allowed me to connect the pieces of my mother’s life and to understand her not simply as such, but as a woman in a body in ever-changing worlds, how the tides of patriarchy washed upon the shores of her heart, and severed her connections to her own mother, notions of home, and belonging. Mothering is such a defiant act in the face of death, the carnage of colonialism; it is an assertion that some connections persist, that to live we die a thousand deaths in one lifetime, and we will do it again and again.

PV: I loved seeing the Hmong language in this book. More specifically, you chose to write many names in Hmong when they, including your own, had previously been written in Anglicized form in your other books. As a Hmong language reclamation researcher, I’m curious about your thoughts, intentions, and hopes behind this choice.

Mothering is such a defiant act in the face of death, the carnage of colonialism.

KKY: I love the Hmong language, the softness of it, the feeling of carrying the wind in our throats, but the decision to write the names in the book all in Hmong was my mother’s. I asked her what she wanted and she told me. I think what results is a gift to readers from all languages, including Hmong speakers. I understand that it is a courageous act, so in this, too, it honors the legacy of my mother, the daughter she has raised. I understand that for many English-reading audiences the names will be a challenge, and that in a racist and linguistically monopolized world, it is more than an invitation to partake in the rich poetic possibilities of the Hmong language, that it can be read as something that makes the book less than, as a decision that could be construed as a liability to my writerly capacity to understand the audiences who buy books. But I do it anyway. I do it because it is my mother’s ask of me. I do it because I love the people who live in these names, walk them in the sun and the rain, and dream with them in the dark of night.

PV: In many parts of the book, your mother fought to hold on to who she was and who she is in the face of war, displacement, loss, and racism. How do you see this characteristic manifest in you and your siblings, all of whom your mother talks about lovingly in this memoir?

KKY: We are all such stubborn people, my siblings and me. From our father, we’ve inherited rebellious hearts. From our mother, we’ve been blessed with this idea that there is a standard we must hold ourselves to—despite all the things that life delivers the marginalized. Our eyes have been trained to see injustice at an early age and our hearts have had to harbor the pain of knowing that the world is unpredictable and governed by forces beyond our control. There is a humility in being Hmong, stateless as we are, war-stricken and often poverty-marked. Each, in our own way, have carried these truths that my mother has never tried to hide from us, and have tried to the best of our abilities to meet them in moments of trial with a measure of the love that our mother holds for us.

PV: Half of your mother’s memoir takes place in Laos and Thailand, during and after the Laotian Civil War, which the U.S. became heavily involved in. How do you think this book and your other works speak back to empire (the U.S. empire specifically)?

I believe in the healing power of tears. It is not a bad thing to cry for a story, for a people, for places lost never to be found again.

KKY: The marker of any colonial power is to sever a people from its history. In the American context, this is the history of slavery, the practice of the Native American boarding schools, and so much else. All of my books work to resist these kinds of deletions. Atrocities happen. To survive, we have done what we can. In each book I write, I do what I can to say: this is who we are, this is how our hearts beat, this is how our lives are lived—despite the secrecy, the efforts to annihilate, the humiliations. We live. We love. We make art. We grow our understanding of ourselves, a little bit at a time because we matter to ourselves and each other, because despite all that has happened, we matter to the world, too. I hope that my books show what is possible; in this way, that they accomplish the impossible in a colonized world.

PV: There are so many stories in the Hmong community, and we need to tell these stories to counter the harmful narratives that have been told about us by people who are not us. But how do we tell these stories that are so closely tied to war and popular ideas and images of refugees without continuously painting ourselves as damaged?

KKY: We are more than the things that have hurt us; no survivor is just the outcome of the violence committed against them. It is imperative that we, as storytellers, paint the full and complex, the terrifying and the beautiful truths that live in our stories. I firmly believe that when you look at Kao Kalia Yang, when you hear her, when you enter into the space of her words, you’ll understand that there is beauty there, that there is tenderness, that there is everything that makes us human to each other. The same is true of Tswb Muas. The same is true of Pa N. Vue. I know these things. We all should. For me, truth is the antidote to the damage in my heart and the way others approach me and my community.

PV: I cried a lot reading your memoirs, and I’m sure I’m not the only one. You put into words what many families in the Hmong community have experienced and are experiencing. Along the same lines of the previous question: how do we, as refugees and as children or grandchildren of refugees, access joy, hope, and healing in these stories that are so hard to hear and to read?

KKY: I believe in the healing power of tears. I grew up as a selective mute in English. When I became a published author and was tasked with speaking to the book I had written, I struggled to do so publicly. My father, at the launch of The Latehomecomer, said to me, “Me Naib, if Hmong tears can reincarnate, they would rain the world in our sorrow, but they cannot so they green the mountains of Phou Bia. If you speak, if the winds of humanity blow, then maybe our lives were not lost.” When I did speak, the words were soaked in my tears; they came from the softest part of me. Without the tears, I would have hardened up. It is not a bad thing to cry for a story, for a people, for places lost never to be found again. It is a gift, a realization of the joy, the hope, the healing that is embedded.

PV: I really appreciated your epilogue, which spoke so much to the longing that your mother referenced throughout the book. It also seemed to speak to the title of your memoir. In many ways, I felt like I was holding a breath, and your epilogue allowed me to release it. Was this something you intended to write? What was the thinking behind it?

KKY: I knew the ending of this book long before I began writing it. I wanted to bring my mother back into the arms of her mother. The question for most of my life has always been, how? In writing this book, I found a way.

There were many moments in the writing when I didn’t know if I could push through but for the thought: I have to return my mother to niam tais’s arms. Similar to you in the reading experience, as I was writing I was holding my breath. I found myself, at the epilogue, finally exhaling. The epilogue is the one part of the book I have been unable to read to my mother. I have tried. I can’t. My mother knows this. This is somehow enough.

Read the original article here