I found Greg Mania through the magic of the algorithm somewhere deep in quarantine, and the feeling I had was that I was late to the party. You could say I was right given their long list of bylines, but you could also say he curated that feeling via brilliant and relentless marketing tactics. Born to Be Public, released by Clash Books in 2020, is his hilarious tale of the heart-wrenching hours that befall a theatrical and closeted kid before he discovers the full scale magic that awaits him on the other side of the bridges and tunnels.

I first met Mania at Nonfiction for No Reason, the literary event series I started in March 2023. Afraid to say hello to this sleeper legend, I finally passed them on the way out, exclaiming, “I love your coffee table!,” an iridescent plastic wonder I’d seen in the tour of his NYC space in Apartment Therapy. “Oh, thank you so much!,” he said, reaching to touch my shoulder, and the warmth was a gorgeous surprise.

Less than a year later, they’d moved to Los Angeles, where I grew up, and I asked him to join the LA edition of Nonfiction for No Reason, which would be at my last family home before I left the city. His piece about searching for home anywhere he could find it had me crying in my old living room. This was the beginning of a dear friendship, and my fascination with Mania’s skillful dance between persona and person, critically acclaimed writer and jokester and extremely sincere human. In a moment of writerly existential crisis, I asked him to chat about how he made all of his beautiful selves. That conversation became this interview over Zoom.

Katie Lee Ellison: While reading your book, I kept wondering: How is it that these incredible opportunities and circumstances keep happening to him? The impression I got was that you wanted it all and you just kept chasing your dreams, a cliche, but seems true in your case. I wonder how much you had that in mind while you were deep in those pursuits, and if you were dogged about your desires as a writer and comedian.

Greg Mania: Born to Be Public is about growing up closeted in Central Jersey, then coming of age as a young adult on the Lower East Side. By the late 2000s, I was hungry to carve a space for myself. I’ve always been very flamboyant and theatrical. Still, I couldn’t find my groove on stage even though I loved performing. In 2009 on the Lower East Side, artists, singers, songwriters, dancers, all these different performers around me were bona fide stars, even if no one above 14th Street had heard of them. I found an artist, Lady Starlight, on MySpace who did this kind of hybrid rock and roll, heavy metal burlesque performance art. Watching her, I thought, maybe I don’t have to just do musicals like Annie. I can still perform in another capacity. Maybe I can figure out how to incorporate more of myself. All I wanted was to find out who I was. What was this insatiable hunger that I felt and how could I bring it to the surface?

Then, I came across this young woman running in the same circles as me by the name of Lady Gaga. I heard some of her music, and thought, “Oh, she’s gonna be a big star.” I was sort of taken under the wings of these performers in a very similar way to Gaga. From them, I learned how to create an image, and how to burn that image into people’s brains, especially when you’re constantly told, “No, you can’t do that, you can’t do this.” They instilled this rebellious spirit in me, so by the time I realized I wanted to become a writer, I had that attitude and realized that people would gravitate towards it. So I got my education as an NYC downtown personality. Starting with my last name, which is Mania (Mahn-ya), but my friends didn’t know it was my real last name and called me Mania (Main-ia). So that’s who I was to them. It’s one way I explored the art of persona and started to test where the overlap was between Gregory, who grew up in Jersey, and Greg Mania, an active participant in the NYC nightlife community. There’s this person that I can embody, who puts their insecurities aside, all the years of bullying aside, and can feel like a superstar, even though no one knows who I am. It’s a healthy dose of delusion. The way you walk, the way you talk, eventually people start to pay attention. And that’s what I learned from my friends in New York.

My goal was to be published in The New Yorker, in “Shouts and Murmurs,” to have a humor piece there, and that’s the only thing I saw. I had my horse blinders on. I was reading those pieces every day, then reaching out to the writers whose voices are similar to my own to get their advice. They didn’t know me; I didn’t know them. I was just emailing them, but more times than not I would get really lovely responses, and I actually became lifelong friends with two of those writers. Within a few years, my stubbornness paid off, and I got my first piece published in The New Yorker.

It’s a mixture of stubbornness, delusion, and the third ingredient is something different. For so many years, I was very hungry, and in my twenties selling my book was the only thing I cared about. As I get older, creating art to share with my friends and community is the impetus for me now.

KLE: What you said about insatiable hunger and the ways that it’s changed: I’m curious if you can talk more about how and why it shifted?

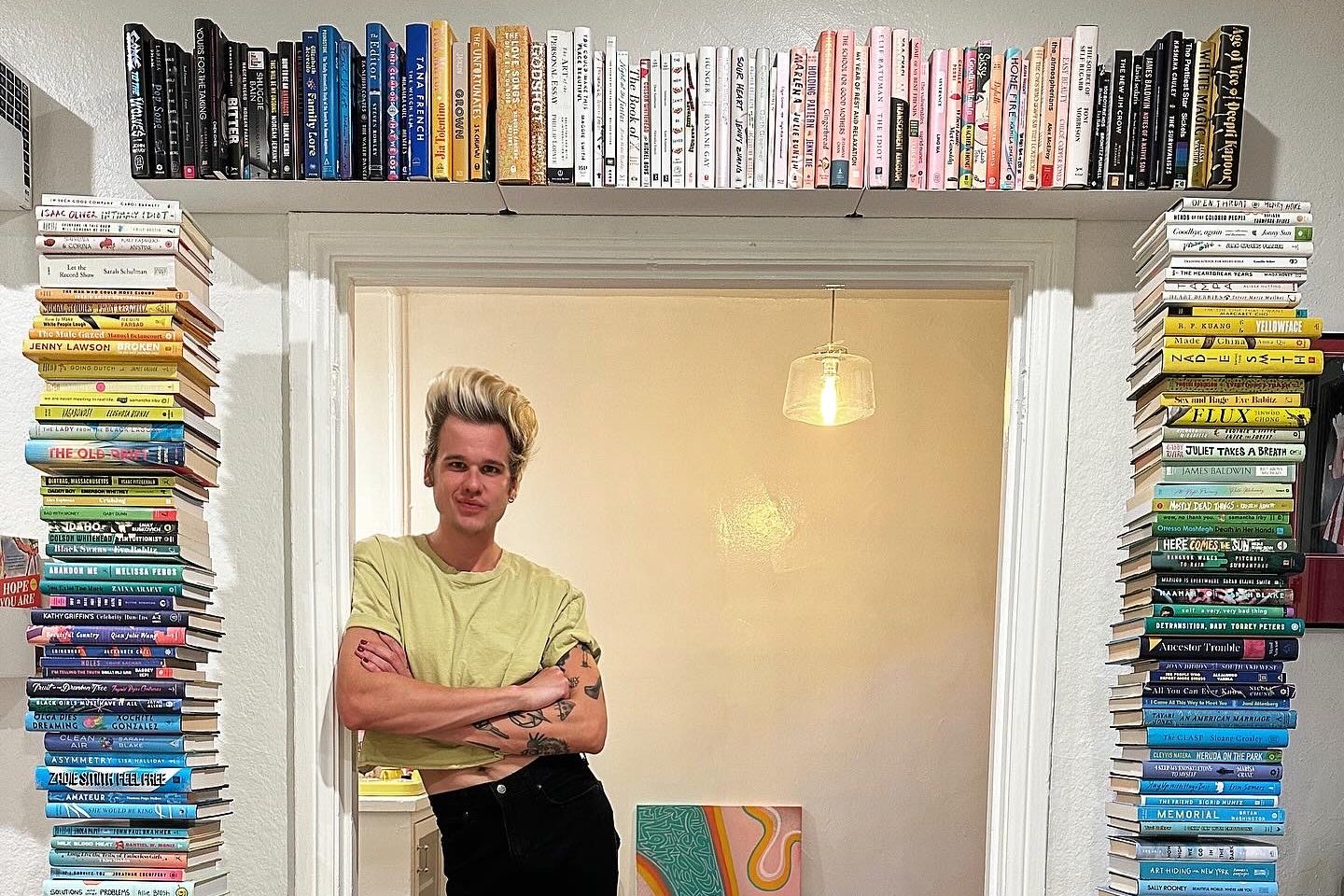

GM: The texture of that hunger and how I apply it specifically has changed. I realized I wanted my voice, my words on the page to be an extension of me, and vice versa, so when you read my work, you hear Greg Mania with the tall hair and you can pinpoint my voice. It was almost a narcissistic drive, but now I feel a responsibility to my community, the literary community, the media community, to drive us forward, especially as our landscape is in perpetual upheaval.

We have to move as a unit, and let that disrupt the powers that be.

It’s more important than ever to galvanize everyone and use the appetite that I have. I feel like I’m 19 again, or 22 being told, “No, you can’t do this. No, the market’s not good right now. No, this is too hard of a sell. Essays are a crowded category.” Or this. Or that. I don’t care about any of it. I know that my appetite needs to be fed by art and sharing my words and hearing my friends’ words, like we did at your reading. It was a moment to get together and listen, to be together. We have to move as a unit, and let that disrupt the powers that be. Let’s grow from the cracks, so we can flourish and let our roots eventually uplift the concrete that has tried to suppress us for so long.

When I say that appetite is still with me, it still very much is. If I have a goal in sight, I can’t stop thinking about it.

The trick is that I don’t have that clear picture of where my work is going to go, whom it is going to reach, after it leaves my hands. The only clear image I have is what I want to say, what story I want to tell. I’ve always had that. But I also feel like it’s too big to consider what impact I’m going to have, or whom I’m gonna reach: it’s assuming too much. I think that goes beyond the power of the writer. Once you let your work out into the world, whether it’s a zine or The New York Times, it’s not fully yours anymore.

I think what’s important, for me, is letting all these different facets of my identity shift and change, come and go, without any self-imposed sway. What I mean is, I don’t want to hide from the parts of myself that I know are there, the things that make me complex, maybe even contradict another part of me. I don’t want to bury these things anymore; I want to feel them, no matter how uncomfortable they make me. I refuse to hate myself. I’ve spent so many years hating myself, going down self-destructive paths left and right. If not to love, I’ve learned to accept those complicated, sometimes dark, parts of me. If I make them visible, others who may have been or currently are in similar relationships with themselves may see something reflected back at them. Sometimes feeling seen and understood is more powerful than any sentence crafted with surgical precision.

I think for folks who are asking, Who’s my work for? I would say looking inward is the only way you can find out who the right audience is. Ask yourself, What do I want to do? What satiates me creatively? What gets me excited? If you’re excited, someone else is going to be, too. That’s the best lesson I’ve ever learned. I thought, “Who the fuck am I to write a memoir? I’m not a celebrity, no one knows about me.” But if you care about your story, someone else will care about it, too. It can be 10 people. It can be 1,000. As long as you are writing from a place of unbridled selfhood and something that you’re passionate about, then you will create a space for yourself. You have to listen to what you wanna do. Let the work pull you.

I think we are always trying to be in the driver’s seat—in control, right?—and something that I’ve learned in the last few years is to let yourself be in the passenger seat for once. Let your gut and ideas steer, and see where they take you.

KLE: What you read at my old house was so lovely and perfect for the event because it was about searching for a home within yourself and the people you love. This feels very central to who you are as a writer and as a person, this search to find your people.

GM: We’re not supposed to ever arrive at a destination of self. We’re always meant to be growing. Just when we think we have ourselves figured out—I think I’m plagiarizing myself—we go and change again. We’re not supposed to ever stop and say, “This is who I am,” because in five years we’ll probably be different. It’s a good thing. I used to be like, Oh, my God, if I wrote Born to Be Public now, it’d be a completely different book. Of course it would be! In many ways, I’m a completely different person. I’m writing a completely different book now. I stopped thinking about all the ways I would rewrite my first book because the author who wrote it, wrote the book he wanted to, that he needed, at that particular time in his life. If you look back on your work and sort of cringe, that means you’re growing. If you don’t look back and want to rewrite, that’s not so great because there’s no trajectory. The destination is perpetual change, an endless search.

KLE: What is your relationship with fantasy and persona? How much does that get you through day to day, how much does it get you through writing projects?

We’re not supposed to ever arrive at a destination of self. We’re always meant to be growing.

GM: I’ve started drafting an essay, and I think it’s called “Reborn to Be Public,” or “Born to Be Private,” something like that. The whole point of Born to Be Public was that I wrote it as both Greg Mania (Main-ia), the nightlife persona, and as Greg Mania (Mahn-ya), the student, and then, the writer. I’ve always existed in duality, because for a while I was a student by day, go-go dancer by night, and always thought I had to operate as one or the other. Never in unison. Through writing this book, that duality became totality. I’m still Greg Mania. Wild, brazen, over-the-top. But I’m also Gregory. A son. A brother. Your friend.

In terms of fantasy and persona, I feel like I’m coming back to my roots. I’m being more honest with myself and becoming more confident. Greg Mania used to be a way for me to contend with self-doubt. Humor is still how I metabolize everything in my life. But I’m really grappling with the concept of home, how to find it. What is home in terms of people and community and places? I think I was very jaded before, and I don’t want to stay that way. I want to be a light. Yes, I can joke about depression, but ultimately I don’t want to run from this tender person that I have recently discovered. Yes, I have that grit and my leather jacket, but I’m also a very soft person, which I used to think of as a weakness. But now, I realize, it’s what makes me powerful. That unvarnished honesty is more freeing than having that sort of fuck-you and fuck-everything attitude that I used as an armor for so long.

I know that I can bring so much love and softness to the people that I care about. Being tender is punk. So I’m growing up and bringing the parts that have formed the foundation of me. I’m renovating a new home over that old foundation.

KLE: I’ve been really curious about how you bridge gaps between a kind of polarity I’ve noticed in the art world as a whole. There’s what I’ll call the critical literary realm, in which Art is G-d and the canon comes before all else, and the communal literary realm, in which work is done to hold up other writers and other people. I see you uniquely positioning yourself in both camps, able to play to a room of high level critique and really belong within a collective. I’m curious if you even believe this dichotomy exists and if so, if you’re intentionally bridging that gap and playing to both sides.

GM: That’s a really fucking great question. I think, on the whole, it’s a spectrum. I do believe there are polarities, but there may be another sort of anchor or nucleus that is your intention, your motivation as an artist.

I have played both camps. In New York, I knew what it-parties to go to; I knew where the photographers were; I’d go intentionally to be photographed and seen because I wanted people to memorize the tall hair, the tall guy, the blonde. That was a way for me to get those performance kicks I was looking for. I wouldn’t even go to the campus deli without a look, and it was fun and fabulous and theater and camp, but I wasn’t always comfortable. It was fun as a 20-something straight from New Jersey who just wanted to be noticed, but it was finite. Sometimes I wanted to just be, and I couldn’t. Ultimately, it didn’t feed me. I wasn’t nourished by it. Now, it’s about visibility, but it’s been lifted from the self to the collective, and that makes me a stronger writer, a better person, a better friend, a better lover. It feeds into every part of my life. Whether it’s sexy or not, that’s in the eye of the beholder to tell us, but I think when you’re going home from some literary salon with a coterie of names upon names and there’s photography and cocktails, versus going to a reading at a bar where your homies are at and you can catch up eating curly fries and talk through your writing woes, you’re gonna be more sated than the other event.

When it comes to bridging those two for me, I am someone that’s very precious with their senses and I’m not going to put anything out that is half-cooked. Some people may think it’s half-cooked, but for me it’s important that I’m sure it’s ready to be taken out of the oven. And some people like their cookies a little extra crispy, some people like it gooey, I like them a little bit in between. So it might not be everyone’s cookie, and that’s out of my control.

I think we have artists for whom everything is for the art, everything needs to be pristine and needs to have a veneer. I don’t think it’s possible to avoid that as a writer. We can be our most unvarnished selves, but the art is still going to impart a message, and that message is always going to have a discrepancy with the true self. To bring it back to persona, you are always dispatching a version of yourself to your readers that you have carefully crafted, regardless of genre, setting up a stage that is based on fact, but your props, your set, your characters are meant to be entertaining. Whether or not you are in it for the prestige, the awards or if I just really want to make my peers laugh. If you are writing no matter what you’re going to care about the quality of it, because you want to do your best job. But once it goes out into the world, I think that is when you fall into those categories. So I think it’s an exchange of how your work is received, and that transmits back to you and can force you to pivot or change direction.

KLE: What’s beautiful to see is that you’re able to put fear and discomfort aside for the sake of this big, growing life.

Being tender is punk.

GM: Fear has dictated my entire life since I was a kid struggling with really intense obsessive-compulsive disorder. My irrational fears of tornadoes and death had me by the throat for so long that I was scared to leave home to go to school. I went to college still apprehensive to be away from home, even though I was only one state away. All this fear, I just got sick of it. This is therapy-speak and so corny, but a self-help book, Feel the Fear and Do it Anyway, really changed the way I thought about fear. I thought, “You know what? I’m just gonna feel it. Yes, I’m scared. I’m uncomfortable. But I’m gonna do this thing that makes me uncomfortable. I’m gonna say this thing that might make me uncomfortable anyway, because I don’t want to live under this looming shadow.” Even two years ago, if you told me I would move across the country from all that I’ve known, I would have thought you were talking about someone else. I was scared. This is the farthest I’ve ever been from my family, but I had to do it. If I didn’t, I would have regretted it for the rest of my life, and I can’t take that chance. Even if I flop out here, then I’ve tried. These feelings of discomfort and fear are so uncomfortable. But those feelings are amplified by a hundred if you try to bury them. Instead of casting them aside, I am learning to coexist with them and finding a sustainable way of operating alongside them.

As for balancing the critical and business aspects of being a writer with community-driven ambitions, I lead by leaning on the relationships I’ve fostered, and vice versa. We share resources, opportunities, contacts, jobs and gigs we think another might be a good fit for, and more. More important than that, writing is a very solitary job, and we spend most of it in our own heads, which can get dicey up in there! We lift each other up, which is the only way we can navigate this tough business without completely losing it.

KLE: Can you describe your genius Blitzkrieg marketing campaign for your book? It’s such a wonder and an incredible model to follow because who gets press can be so deeply biased: who gets access to bigger platforms.

GM: The marketing campaign for Born to Be Public operated on complete and utter delusion. My publisher, CLASH Books, was a much-smaller press at the time. There wasn’t an in-house publicist. No marketing budget. We had to do most of it ourselves. I had saved up enough to hire an independent publicist, who was wonderful. But the M.O. was the same from the get-go: We were going to act like this was a lead, Big 5 title. I had already established relationships with a number of editors, authors, and other folks in the media world by virtue of my freelance work. That one editor who passed on a piece a few years ago, but who encouraged me to send along future work? They ran an excerpt in The New Yorker. That person with whom my friend connected me at that one mixer a few years ago? They put my book in a highly anticipated list. I went to school with the assistant books editor at this huge magazine, and sent her a galley. Boom, we’re in Oprah Daily. Shoot for the fucking moon. The worst thing that can happen is you get a no, or no response at all. You might as well go big; you don’t have anything to lose.

Also, platform doesn’t necessarily equate to book sales. We need to dispel this notion entirely. Remember when White House staffers were getting fired left and right during the previous administration, and there was one publisher in particular making it rain book deals on them? Girl, these folks got six-figure book deals for a book that no one asked for or cared about. And if they did hit The New York Times bestseller list it’s because—and I need to be careful here—it was because they allegedly bought the thousands of copies they needed to make the list, allegedly through one of their LLCs or some fakakta foundation they run, but then their book just disappeared into the void. Now, I’m not going to name names like Meghan McCain, but c’mon. Millions of dollars spent on a book that no one gives a fuck about when there are so many emerging voices; that’s millions of dollars that could be going to writers with unique points of view, stories that are destined to be told.

I understand that publishing is a business. And yes, there are bestselling books at imprints that single-handedly keep the lights on. But both of these things can be true at the same time. The media landscape is in complete disarray—layoffs, mergers, dissolutions. It’s scary, for everyone. But I also think this instability is going to foster a very necessary paradigm-shift, which I hope will be community-driven. I have faith in the work we are doing as a community. And I’m not talking about the huge commercial names you see when you walk into a Barnes & Noble. I’m talking about the writers recommended as staff picks at your local independent bookstore. Those are the people I hope spearhead that shift.

Read the original article here