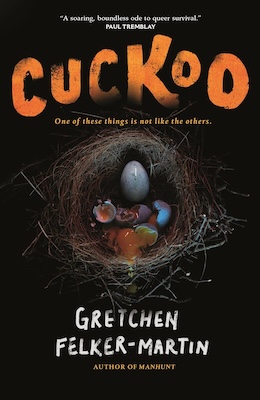

Horror writer Gretchen Felker-Martin’s sophomore novel Cuckoo follows a group of teens in the 1990s who have been abducted and abused in a remote desert camp all on their parent’s dime. What begins as a real-life nightmare quickly reveals itself to be something much more insidious, forcing these friends, forced by circumstance, to stop the cannibalization that seeks to destroy their minds, families, and communities with no end in sight. Amplifying the shame and discomfort of queer adolescence under the tyranny of violent, unchecked hegemony, Felker-Martin reveals through spine-straightening terror and whispered intimacy that the only hope is the action taken to protect those we love. Without it, we are all just waiting for our turn in the slaughterhouse.

In Cuckoo, people are rarely as they seem. There can only be an “us” and a “them” if there is a way to know the difference. Safety can be found in someone you barely know and a threat in the face of a loved one. The kids of Camp Resolution reveal that the immutability of a child’s identity is as widespread as the instinct to control it through whatever means necessary. The power of each lies in its ability to fester unchecked, toward authenticity or conformity. Abused teens turned traumatized young adults reveal that sometimes the only choice to be made is the one you don’t want to make: the one that won’t fix your pain but maybe alleviate someone else’s. The world can’t be saved, but maybe one kid can be.

I spoke to Felker-Martin over Zoom ahead of the novel’s release to discuss the true meaning of community, the encumbered path of queer, adolescent discovery, and America’s hatred for its own children.

Christ: Where did the conceptualization for Cuckoo start?

Gretchen Felker-Martin: This book comes from a decade of helpless rage at watching people pointlessly abuse queer children. It’s not like it even does anything other than ruin our lives. You don’t get straight people out of it. You don’t fix anything or create any relationships. You’re just torturing human beings, out of a combination of willful ignorance and sheer sadism. Being a queer adult puts you in this uniquely powerless situation where you have to watch as this happens over and over, immediately around you and in the country at large. I needed somewhere to put those feelings. It’s a great big middle finger to all of these people doing this to children.

C: The mechanisms of queer experience and the horror genre align so well in terms of the things we know but can’t admit or the things that we feel but can’t articulate. Did that play into your writing process?

GFM: That’s always important to me when I’m writing. Horror is all about unspoken drives, desires, and fears. If you can sublimate that on the page, you can elicit a reaction from the reader, and you can give someone the relief of knowing that they’re not alone with their forbidden thoughts or shock someone into wondering why those thoughts are forbidden in the first place. You can push people into a space where they have to start questioning the architecture of their own mind and the world around them.

C: The story starts with friends thrown together by the powers that be and ultimately sidesteps the cliche of “chosen family”. I was wondering what you think about the bonds formed within the core group of characters versus those that reach across generations.

GFM: Those bonds are vital. They’re very much of a piece with the connections that we have with our peers. I’m lucky enough to always have elders in my life. It’s informed so much of who I am and how I think about the world. People take it for granted so easily. We’re all expected to have some experience of our grandparents and their lives, but queer people don’t always get that luxury. And I think that even if you are forced into something like that by circumstance and cruelty, that doesn’t mean that there’s no meaning in it.

C: The splintering among the core group, their resentments of one another comes through, but so does the commitment to showing up for one another.

GFM: They’re there no more or less fractious than any real group of siblings. So often we group ourselves together in this overarching way. You hear a lot of people talk about the “queer community” or whatever, but that’s not a thing. You might not have anything in common with your local queers. You might not have any involvement with them. You might not share politics or beliefs. Your queer community is the people that you actually form a community with through actions. Who do you have material ties to? Who do you spend time with? Who supports you, and who do you support? Those things are community, and I really want to dig into that with the book.

C: Much of the context for the book ahead of its release has to do with the idea of queer survival. Do you see this as a novel strictly about queer survival?

GFM: That’s certainly at play. Really, I’m getting at a fundamental rot in America. We hate our children, and you can watch it play out right now on college campuses all across the country. People with college-age children screaming and saying to have the National Guard go in and kill and beat people for protesting genocide. You have a generation of hardened, embittered political conservatives who are willing to do anything for seemingly any reason. And once they’ve started doing it, the suggestion that they should stop is so unthinkable that they’ll turn on their own young.

C: Do you remember when you first learned about the cuckoo’s egg conceptually?

Your queer community is the people that you actually form a community with through actions. Who supports you, and who do you support?

GFM: Oh, I was a kid. I was such a nature fanatic. And brood parasitism is such an interesting phenomenon. There’s just something so potent about it, you know? And we’re we’re so leery of it that we have thousands and thousands of cultural myths about it. Changelings and baby snatchers. It’s a frightening thought. It all boils down to this parental anxiety: what if my child’s not what I want? Which is ultimately such a selfish fantasy.

C: Horror involves leveraging what is exposed against what is left unknown. How did you tow that line?

GFM: I’m on the side of leaving things unanswered. With the Cuckoo, we get to see snapshots of its existence as some sort of collective intelligence, but those are glimpses of something much bigger. Ultimately, that drives the fear and cosmic horror. You want your reader to feel like there is so much more just outside the scope of the page. You want to give them just enough information that they know how little they know.

C: The same can be said about queer children in terms of access. You only can know as much as you have access to. How can you be something that you don’t know even exists?

GFM: You usually can’t. Some kids have an abnormally strong sense of self, or they encounter some key image in childhood that unlocks something for them, but for most of us, you’re stuck in the box you’re given to a greater or lesser extent, and you might have urges, daydreams, and ideas about yourself, but you can’t place them in a context.

C: There’s a recurring mechanism throughout the book where characters have thoughts seemingly beamed into their heads. One of the most striking is when a character realizes they’re trans. You are never able to consider it. Then one day it just becomes completely clear.

GFM: I also came out in the desert. I was out in the middle of nowhere. Having a mental breakdown. And one day I was just like, yeah, I’m not a guy. That’s what’s killing me.

C: Yeah, I had a very similar experience. On the topic of discovering one’s own transness or living through the dull, lifeless experience of having not discovered it. Have you seen I Saw the TV Glow?

Horror is all about unspoken drives, desires, and fears.

GFM: I did. That was a hammer to the solar plexus. What a film. I was blown away. I’ve been lucky enough to get to talk with Jane a bit, over the years. And I love their work. The image of this helpless, little boy child curled up in his room watching a TV show for girls and making it his whole identity. It’s so close to home for so many women in our generation. [That film] is a really incredible experience. I’m really happy to be alive at this moment in history, in spite of everything.

C: One thing Cuckoo does so well is exploring the capital-A Authoritarianism that we live under through the lower-case authoritarianism that happens in the classroom, in the home.

GFM: I was raised in a pretty strict religious setting. Pastor Eddie is based on a real guy that I knew. There’s a sadness to these people, looking back as an adult. To see someone so fixated on controlling children and so unable to understand them on a basic level. Any of the mechanisms by which you could actually hope to influence a child positively, these people have no interest in that. They’re incapable of accessing them. It’s just pure power.

C: The book complicates the idea of “us versus them” and challenges the idea that those categories are even discrete, especially toward the end with the reveal of Pastor Eddie’s history and the final scene. It posits that even those in power are not always as empowered as they seem to be.

GFM: They’re not. They’re trapped in their own worldview, too. At the end of his life, Fred Phelps, the Westboro Baptist guy, recanted a lot of his homophobic beliefs. He got ex-communicated from his church and wound up dying alone and impoverished. This is guy wasted decades on horrendous hate campaigns and came to the realization—whether it was through encroaching senility or some kind of moral awakening—that he had missed all that time. He had done all these awful things and tried, with what time he had left, to repair it, but it was too late. He was he was stuck in said the world he made.

C: That echoes the experience of queer teenagers who are prisoner to the will of their surroundings. Later in the novel, you say the Cuckoo “hates work,”ultimately leaving the dirty work to humans. Especially frightening is that i’s not only outward bigots that end up playing into its plan, but also those who see themselves as compassionate. There’s the quote from her post on a Reddit-like forum from a concerned parent of a queer child asking “Am I the problem?” She’s so close to maybe seeing the light of understanding, but she can’t get there.

GFM: I find that stuff endlessly fascinating: the psychology of people who identify as alienated and abandoned parents. It’s so horrible, deeply self-victimizing, and sick. I’m shivering just thinking about it.

C: There’s that idea of something being done to them when they are the ones with power. Cuckoo is not just about authoritarianism in relation to queerness, but also to gender, family roles and body politics. This web shows how all of those mechanisms for control ultimately lead to this absence of humanity.

GFM: Yeah, I think that they do. Our participation in these systems of ostracization and oppression inevitably leads to a poorer, blander, more painful existence for all of us.

C: What about queer teenagers makes fatness as an object of desire and disgust so ripe for exploration?

I’m getting at a fundamental rot in America. We hate our children, and you can watch it play out right now on campuses across the country.

GFM: These are human beings who are just figuring out their sexuality and their body image. That is a messy process. There’s nothing clean about it. They are synthesizing their feelings with the way they’ve been treated and the things that they see or think they see in the people around them. Pop culture and religious backgrounds: all of these conflicting, intersecting things. The result is so nebulous. There’s still so much up in the air for them. With fatness especially, you have this sharply penalized state of existence where your body is both de-sexed and very, very hypersexualized. At the same time, you’re left totally alone and unable to contextualize your own experiences of sexuality. All this stuff is stripped away from you and taken from you. Desire for fat bodies is also so shamed and marginalized and can create a lot of conflicting feelings within everyone involved. It’s ugly and complicated and thorny.

C: In the intimate connections, you see the revelation of desire for fatness fighting that external voice coming and forcing characters to ask questions like “Am I allowed to want this? What are other people going to think of if they know that I want this?”

GFM: Right, the shame. The chaser thoughts.

C: I was wondering about the choice to make the ultimate revelation that the matriarch is pulling the strings.

GFM: So often modern third-wave feminism has encouraged women to put the blame for culture’s ills on the shoulders of men. Certainly, that’s an understandable instinct. There is a tremendous amount of suffering that can be laid directly at the feet of men, and it should be addressed specifically in those terms. But in so doing, we often forget what women uphold. As a man has power over his wife and can abuse her and exploit her, women have that power over children for the same reason: they have culturally accepted authority. They have more strength. They’re larger physically. And what does someone who is systematically abused usually do? They abuse the people who are weaker than them. You create a pecking order. Women are very dangerous to children. They abused children very frequently. As a society, we largely choose not to see this or to consider it normal and not worth stopping or addressing. Women are just as prone to policing issues of sexuality or gender. They may even be more fanatical and intense than their male co-parent because of the limited scope of their own lives. Especially women in conservative situations who have a diminished social role. That certainly played a large part in my life. Luckily enough, not my mother. I was surrounded by very religious women who had an intense sort of psychosexual fixation on the lives and burgeoning sexualities of the children around them because those were the things that they could control, and they were the things that they had power over.

C: There’s also just such a deep, deep irony in that trans women are portrayed as a huge and pressing danger to children constantly.

GFM: This is one of the huge acts of transference that we accomplish as a culture when we have a real problem that’s so horrifying and so overwhelming. We just completely avoid the conflict, and we go ahead and create some sort of proxy for it. You know, we talk about violent video games instead of the fact that we have an imperialistic, expansionist military, and every American city is run and ruled by an armed gang. Instead of confronting the very real and very provable fact that children are most likely to be abused by their parents, we invent the specter of some Calabar lock-fingered drag queen. These are the willful delusions of painful, stupid people and unfortunately, those people often have a lot of power.

C: In the final chapter, you interpolate lines from Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky. Aside from the obvious parallel of killing a monstrous creature, how do you see that work in conversation with the themes of Cuckoo?

The cuckoo represents the straight world and the urge to assimilate and disappear into this all-consuming mass that gives you a recognizable identity and way of being.

GFM: It’s a very famous example of a nonsense poem, the creation of new language to evoke feelings that aren’t quite in the consciousness yet. We can kind of intuit what a jabberwocky is, what these movements mean, and what the descriptors that Lewis uses are meant to evoke by their similarity to other words taxonomically. It’s this sort of trying to make sense of senselessness. There’s an element of gobbledygook to it that was really important to me in my conception of the cuckoo, which is an incoherent creature, fundamentally. It’s a being of pure desire that exists and affects others based on these pure desires.

C: The desirous nature of the cuckoo is at times in opposition to queer desire, but it also feels parallel to it in the way that it can’t be stopped or denied.

GFM: In a lot of ways, the cuckoo represents the straight world and the urge to assimilate and disappear into this huge, all-consuming mass that gives you—no matter how miserable, lonely, and unrealized you are—a recognizable identity and way of being. You know what to do. You have a script. You’re never technically alone. The cuckoo is like a giant, all-consuming suburb. It’s comfort, convenience, and ease. And those things can feel good temporarily, but really, they annihilate you and hollow you out from within.

C: There’s a phrase that comes up in Cuckoo, and I’m wondering how you think about the idea of “hoping against hope.”

GFM: I see it as necessary. I have spent my life watching the country where I was born do terrible, terrible things all around the world and at home. The cultivation, first of hope that things could be better, and then of material ways to try to manifest that change has been vital to my ability to exist as a human being without going totally insane. The more we can create that kind of latent subconscious and conscious desire for something better. The more we can start to pull it into reality. I hope that’s true. I probably won’t know in my lifetime, but you have to.

Read the original article here