Based loosely on a Grimms’ fairytale, Bear is both enchanting and suspenseful. Sam, a concessions worker on a ferry, is terrified when a bear shows up at her family’s front door. Elena, instead, grows enchanted by the bear, seeking him out in the woods and bringing him food from her job at the local country club. As Sam panics over Elena’s behavior, and both sisters worry about their mother’s failing health, the novel hurtles toward a devastating conclusion.

The idea for Bear, the second novel from Julia Phillips, was born during Covid lockdown. Stuck in her New York apartment, Phillips tried to imagine “like the farthest-flung, most fantastical, most beautiful place I could imagine actually getting to” when travel became possible, and settled on the San Juan Islands, off the coast of Washington State. Her feelings of isolation became a novel about the financial impact of Covid on the working class, what we owe to our families, and finding liberation in the natural world.

On our Zoom call, Phillips, a National Book Award nominee for her debut Disappearing Earth, is thoughtful and introspective, speaking slowly and deliberately until she explodes into a burst of enthusiasm or laughter. Her book, she tells me cheerfully, is “like Jaws, but the part where they’re just in the water. And you’re like, Oh, God. At least, that’s the hope.”

Morgan Leigh Davies: In Disappearing Earth, many of the characters are isolated, but the structure of the book creates a community out of them. This book is all in the head of one person [Sam], and it’s a character who is really resistant to being in any kind of community or relationship with anyone but her family. How do you approach the shift between the two books?

Julia Phillips: To me, the message of Disappearing Earth was the idea that connection can save us: that when we come together, we can save each other. I think this book’s argument is that disconnection destroys us. We’re just in one person’s head and the willful isolation that she embraces ends up really hurting her situation. It keeps her from accessing help. It also created a lot of propulsion and fun.

I think that I am always going to be preoccupied with subjects of survival and violence and womanhood and community. But I think I was pushing against the hopes I’d had more in this book. I was not so committed to a hopeful depiction as I was in the first one.

MLD: So much of the novel is driven by Sam’s fear. I wonder how fear functions in this book, and how it creates a sense of propulsion in the novel.

To be somebody’s everything is a real burden, although it can be joyful or validating.

JP: My own taste in reading is toward the page turner. I love to have a book where I don’t want to ever set it down. I felt the whole time writing Disappearing Earth that I was struggling against that foundational aspect of it—I really wanted to create a feeling of momentum and cohesion and the structure I’d chosen gave me some pushback. For this, I wanted to write a book that made me feel that way. I wanted to write something that feels like you just fall in the river and get swept along, like it just pulls you forward.

The theory I had was that the more cohesive we are in feeling with Sam, the more we are behind Sam’s eyes and in Sam’s head and in her body, the more clear we are about what she wants and what she’s trying to do to get it, that that would create a feeling of total immersive momentum. I think it was challenging with her because she has so much fear and anger and defensiveness. It can be hard to sit inside that so much.

MLD: We should talk about the bear. It is one of the main characters of the book, and we don’t have access to what it is thinking, what it’s feeling, what’s motivating it besides eating. I was wondering what the appeals and challenges were of writing about forms of life that exist outside of our understanding in that way.

JP: This is a story of human reactions, human relationships, symbolic interpretation, and the animal is having his own experience to which we do not have access. Maybe Elena does have some sort of access… I think she’s able to sort of vibrate on the bear’s frequency sometimes, but Sam does not wish to vibrate on his frequency. Sam has a very, very human understanding of what [the bear] wants, what he’s doing, how he’s behaving. And it blocks her from any desire to even ask what he’s thinking.

I found the portrayal of the bear in this book to be an absolute joy. I just loved writing this animal and I loved writing this animal from this exterior position. He’s a mystery to the characters. They don’t know why he’s behaving the way he is. They don’t know where he came from. He is his own thing in the world. It was so fun to play with this beast and say, here he is, he doesn’t obey your rules, he doesn’t do what you want him to do. He just is his own thing, and he’s beautiful, and he’s scary, and he’s stinky. I definitely felt like I was vibrating on his frequency.

MLD: I think one of the places that the real tension comes from or for me, as a reader, is that both the sisters are right and wrong about the bear. Sam is obviously correct that her sister should not be feeding this bear in the middle of the woods.

[The Covid era] is extraordinarily influential on our lives today, and is continuing to shape our every day.

JP: Absolutely not. Do not, do not do that. But also…

MLD: But she’s so afraid that she can’t see what is wonderful about him, and Elena can see that. But Elena’s doing foolish things. I’m curious how you thought about balancing those two perspectives and the relationship between those characters as the book was coming along.

JP: I think Sam came out of a couple of feelings that I’ve had. I really love fiction as taking what’s in our own lives and turning it up two notches on the dial. And she is the turned-up version of some feelings that I’ve had, or relationships I’ve had in my own life.

One of those feelings is a little sister feeling, where you are so admiring of the older sibling, or taking the older sibling as a model for the way to be for at least a certain amount of time in your life. But the older sibling’s world is bigger than yours, and they have more life, and you’re watching and following. I think that dynamic is very interesting and influential and hard. As a little sibling, especially in teenage-hood and my early twenties, I found it really hard to see my older brother, in my case, begin an adult life, leave the life of the nuclear family, and move on, in a way that I was not ready to yet.

The other influential character-shaping feeling that went into Sam is around experiences that I’ve had in friendship. I’ve had some very, very close friendships in which one person says, I’m going to be your best friend. I’m going to meet my own high expectations for what friendship is, and I would like you to also meet those expectations. I’ve found those experiences to be challenging, because that level of dedication is really hard to maintain. To be somebody’s everything is a real burden, although it can be joyful or validating.

Sam has decided because of her own experiences that Elena is going to be her everything, and Elena has been used to being someone’s everything. What does that do to the relationship? What space does that open up for dishonesty or disappointment or deceit? Or to be frustrated with the person because they’re not doing what you think they should do?

MLD: I was really taken with the framing of this as being from a Grimms’ story. How did you draw on that story, especially from the fact the originals of these stories are usually quite dark? In particular, the relationship between Elena and the bear is described as romantic pretty consistently throughout the book. At one point, Sam says, “You’re talking like you want to kiss it.”

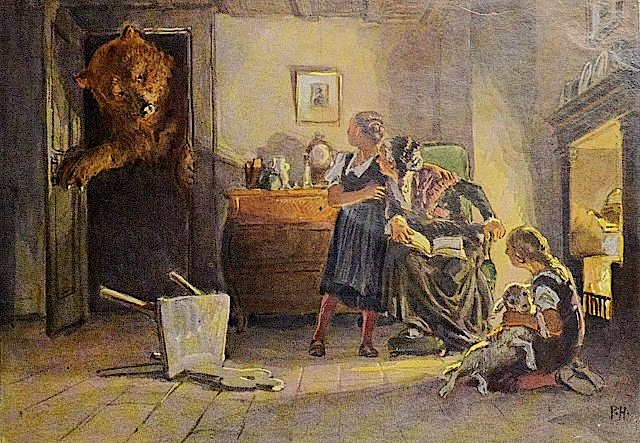

JP: So the original fairy tale that in very broad strokes inspired this [is about] these two sisters in this cottage with their mother, and a bear comes to the door. This fairy tale from the Grimm Brothers is called “Snow White and Rose Red.” I was obsessed with this fairy tale in particular, and my whole collection of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, as a kid for a long time. I was obsessed with them for exactly that reason, that darkness.

In it, this bear shows up, and the bear is enchanted. At the end of it, the older sister ends up marrying this prince who had been enchanted to be a bear. So she marries the bear after he is un-beared on the other side of his magic spell. But before that they have this relationship where they were rolling on the floor together in this intense bond for months and months, and I thought, What is this? As a kid, I would try to rewrite versions of it and I could never make it work. So this was my big bite at the apple. I really wanted to try it and to see if I could retain those shocking and perverse elements, and that fairytale feeling, but take those elements and map them in a new way so they would feel more satisfying.

The relationship that Elena has with the bear… Sam doesn’t understand it. She talks about it like a romance because that’s one way that she’s trying to make sense of it. She’s trying to say, Well, is it this? Is it this? Does it fit in this box? Does it fit in that box? Because it’s a very confusing thing to her. I think it is sort of unmappable and uncategorizable to Elena too. What I think the bear does for her is absolutely passionate and physical, but it’s not sexual. But it is very exciting.

When I was working on this manuscript, I read a lot of the genre of woman in relationship with animal, or woman in relationship with creature. Sometimes it is sexual, but sometimes it’s a friendship and sometimes it’s a self-negotiation, like an animal coming out from inside you. There are all these different relationships and all of them are reckoning with the idea of women whose roles have been super constrained in the human world who are not happy with the role they lead in society. Having this encounter, whatever the encounter is, lets them move out of the world that they were in. It lets them say, I get to be wild, I get to be free and the externalized animal is just a way for me to access the internalized animal and a way for me to leave the world that I’ve found so constraining and so stifling and see what else is out there.

I think that is the experience Elena’s having. Her days were really limited and now something is changing the routine and it’s opening up her days in ways that she never anticipated before. Through encounter with this animal she gets to feel freed of her responsibilities, of her stresses, of her fears, of her worries, just feel free. Of course she’s chasing that.

MLD: I was really curious about the decision to include Covid in the book and in a meaningful way. A lot of recent novels take place in 2019, or conveniently avoid the topic. But it’s obviously had a really significant financial impact on the family here. It felt really real to me.

JP: It felt really important to me. I think we’re in an avoidant moment with our recent history, and we don’t want to talk about Covid, or write about Covid, or read about Covid, because we just lived it and we’re currently living in it, so maybe it feels too close or too painful or too raw. This era is extraordinarily influential on our lives today, and is continuing to shape our every day. Of course, we wish that were not the case.

I really enjoy contemporary fiction. I want to write contemporary fiction at this moment in my life. And if I’m writing something set right now, I just have not been able to make the leap to imagine someone who is not shaped by that experience. These are characters who have a mom who has lung and heart issues, who live in a tourist economy where the bottom dropped out in 2020, who were always having trouble making ends meet. The idea that by 2022 or 2023, they would be saying, “Oh, you know, Covid, that whole thing—never heard of it!” It just didn’t make sense to me. It wasn’t a two-week tough thing. These were years of their lives that were changed by this, and ripple effects that are going to go on forever for them. So I tried to put that in that way.

Read the original article here