For a long time, much of what was published about El Salvador was a grim monolith, authored by outsiders: gringo historians, mid-century anthropologists, Céline models. If you read Joan Didion’s terse little book on the place, Salvador, you might have the idea that “terror is the given of the place.” I could write for a long time about the historic erasure and suppression of Salvadoran writers, about the limitations of imagination in certain literary markets, about perverse appetites for humorless, untextured stories of suffering, about stories that don’t even go to the trouble of imbuing their characters with human consciousnesses and instead allude to “faceless brown masses.” To rephrase another visitor to the country, Carolyn Forché (in my opinion, a far more perceptive witness): what you have heard is not exactly true. What’s been left out of these explanatory narratives, what you may not have heard about the place, is a rich variety of Salvadoran voices. The people of El Salvador and its diaspora are more than vessels for terror and misery, and perfectly capable of artfully telling stories, and of writing into desire, joy, and even the nightmares of collective memory, on our own terms.

When I set out to write my own novel The Volcano Daughters, I had to contend with that grim monolith. Despite it, the voices of my narrators (and their cackles, bossiness, secrets and desires) were vivid in my ears. I heard their voices in my siblings, my friends, and in the lines of the poets I admired. I grew up in San Francisco, and El Salvador was my father’s country, a place I had only visited. Growing up we ate pupusas at El Zocalo, but I didn’t speak Spanish fluently. My connection to the place, only half a generation away, felt distant, in terms of family, myth, and history. Reading many of the books on this list affirmed the specificity of my own diasporic relationship to the place, and I found myself in community.

I’m heartened that more writers from the Salvadoran diaspora are being published and more Salvadoran writers are being translated and reaching wider audiences now than in previous literary eras (though, traditionally published or not, there are writers on this list who have been writing for decades.) Three of the books on this list were published just in the past year. Three are recent, excellent translations. These books—poetry, short stories, memoir, novels, myth, and even a cookbook—represent just some of the writing that comes from El Salvador and from the Salvadoran diaspora in the United States. These writers create work that transcends token representation and instead offers, to curious, discerning readers, visions of surprise, transformation, mischief, memory, grief, sex, food, dreams, formal innovation, and the future.

The Popol Vuh, translated by Michael Bazzett

The words “Popol Vuh” mean “the book of the woven mat.” Poet Michael Bazzettt’s translation of the Mesoamerican creation story is an intricate epic that subverts the laws of linear time, and it’s full of mischief, beauty, and a very metal cosmology. Ilan Stavans’s translation of Popol Vuh is also an excellent introduction to the oldest book of the Americas, and it features some gorgeous illustrations by Salvadoran artist Gabriela Larios, as well as a great foreword by Homero Aridjis.

The Dream of My Return by Horacio Castellanos Moya, translated by Katherine Silver

This short novel is a maniacal, paranoid, somehow delightful rant narrated by a writer with liver problems (hypnosis isn’t taking; could be the poor quality of rum he’s drinking) on the verge of returning home to El Salvador from his exile in Mexico City. His mysterious old friend, Mr. Rabbit appears in the midst of this madness, often at a taco shop, and invites him to participate in half-baked criminal plots, green salsa dripping through his fingers.

Stories and Poems of a Class Struggle by Roque Dalton, translated by Jack Hirschman and Barbara Paschke

Roque Dalton, who wrote that “we were all born half dead” after La Matanza massacre in 1932, and that “I believe the world is beautiful and that poetry, like bread, is for everyone,” dedicated his life to anti-fascist revolution and poetry before being murdered by his own comrades. This volume contains a comprehensive collection of Dalton’s poetry voiced by five different heteronym personas, as well as several brilliant essays from poet Christropher Soto, Margaret Randall, and others, which place Dalton’s work in its time, and highlight his relevance today.

Slash and Burn by Claudia Hernández, translated by Julia Sanches

This novel takes on the long aftermath of war and separation through the voices of a family of ordinary women—four daughters, one estranged, and their mother, an ex-revolutionary. When the mother leaves the country to travel to Paris to reunite with the adult daughter who was taken from her and adopted by a French family during the war, a frame opens up in the narrative, forcing the mother, an interpreter, and the unknown daughter, to return to a place and time beyond memory. Part dreamy haunting and part bureaucratic tangle (“Her mother’s life story doesn’t fit in the assigned box on the university’s financial-aid application form”) Hernández’s novel is astonishing. About her book, Hernández says, “It’s nothing. I don’t do anything. I just listen.” Sanches’s gorgeous translation honors Hernández’s subtle, poetic structure that shapes each line.

Mucha Muchacha, Too Much Girl by Leticia Hernández Linares

Hernández Linares is queen-comadre of San Francisco’s Mission District arts and culture scene. I fell in love with her razor-edged words, her poetry and performance art, her commitment to justice, community, education, and to mothering. Her work introduced me to Prudencia Ayala, “the girl with the birds in her head,” a Salvadoran poet of the 1930s who ran for president before women could even vote. Decades later in San Francisco we became friends and literary co-conspirators. But let me tell you about her poetry. This woman takes on academic machos, centers community in the midst of gentrification, and conjures La Siguanaba walking down 24th street in tacones, all her power reclaimed from the myth’s shallow waters. The images in this collection will break your heart and nibble on your tongue. In “Luna de Papel,” she writes: “I tried to wrestle with the moon/y me mordió la lengua.”

Unforgetting by Roberto Lovato

Lovato’s tender, intense, sweeping memoir is a love letter to his complicated father, and a commitment to unearthing the truth where it is buried. Lovato makes explicit the deep, exploitative, and counterrevolutionary ties between the U.S. and Salvadoran governments that are responsible for the terror. From a forensics lab to the Evangelical churches of San Francisco’s Mission District to his grandmother’s sewing machine, Lovato takes readers through the heart of histories he refuses to leave forgotten.

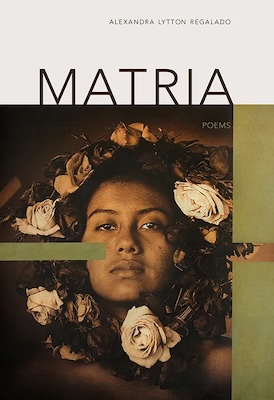

Matria by Alexandra Lytton Regalado

Regalado’s poetry draws lavish lines between El Salvador and Miami, Florida as she writes back through her familial history and interrogates motherhood, class, power, bonds, and ruptures. From her poem “Salvadoran Road Bingo”:

“Every car is a carreta bruja on this highway, we’ve gone Red and bathed in red, oh deep colors bleed, a poem I found on the wash tag of a bath towel when I was twelve. Ours is the luck of my great grandfather who, one night, like any typical night, in a game of cards, lost a velvet sachet filled with his wife’s diamonds, and the title of their house. The cantor calls out the Lotería in a riddle: El Salvador whom is going to save us, whom are we to save? Day after day, our fingers in the wounds—here it is, touch it, there is the proof—surviving is what we do best.”

There is a Río Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

The stories in this collection are playful, hilarious, queer, and delightfully speculative. They imagine new worlds and write into boundless futures. Reyes’s stories are formally inventive and delightful. A taste for mangoes leads to elaborate familial exploitation. A son comes out to his dead father, who has returned in the form of a tiny robot. One story title iterates throughout the collection, inviting the reader to imagine an alternate Salvadoran history, or perhaps the world, in which the Pipil defeat the conquistadors in 1524, or in which a tyrannical dictator leads an excavation of dinosaur that brings fortune to the country. Is terror present, too? Yes. In that dinosaur story the bones are human, unearthed and refashioned into a lucrative fiction for the patrimony: “It was 1941. The memory of the massacre nine years prior was still in sight. Terror hid and rewrote details about everything, including the discovery,” Reyes writes.

The Salvisoul Cookbook by Karla Tatiana Vasquez

This is no ordinary cookbook. It’s culinary documentation, historical research, and an archive of memory. And, Vasquez’s book, published in 2024, is the first traditionally published Salvadoran cookbook. Growing up in Los Angeles, surrounded by Salvadoran cuisine, Vasquez wondered why she couldn’t find any Salvadoran cookbooks. War and its destruction of cultural artifacts was one reason. Aforementioned flawed capitalist notions of “what the reading market truly desires” is another one. Recipes for quesadilla, pupusas, riguas, flor de izote (the edible national flower) yuca frita, and curtido were carried on the tongue. So Vasquez sought out the recipe-holders–friends, relatives, and community members–she calls them the “SalviSoul women.” In the pages of this book are recipes, and ingenious consejos from the SalviSoul women (stand on a ladder while stirring masa for more leverage). Especially compelling are the stories that some of the women share along their recipes and consejos: Ruth draws a throughline between losing her shoes during her journey to the United States as a child and later selling pupusas to a sweaty Leonardo DiCaprio at Coachella; Estelita remembers her last night in her beloved grandmother’s adobe home before leaving to join her mother in the United States; and on returning to El Salvador after decades away, Isabel says, “Tu corazón no puede renunciar a su tierra,” (Your heart can’t give up its land.)

Unaccompanied by Javier Zamora

Zamora’s debut poetry collection includes persona poems from young parents, and vivid moments of pain, abandon, and love. It’s a gorgeous map of the world that he writes about later in his memoir Solito, infused with music, longing, and rage.

Here’s the close of “The Pier of La Herradura”:

“There’s a village where men train cormorants

to fish: rope-end tied to sterns,another to necks, so their beaks

won’t swallow the fish they catch.My father is one of those birds.

He’s the scarred man.”

Read the original article here