An Excerpt from Mother Archive by Erika Morillo

When Papi “disappeared,” my paternal grandfather paid Balaguer a visit to the presidential palace. He was allowed in only because as young boys, they had gone to school together in the city of Navarrete, the memories of those days softening the president into hearing Abuelo out.

“Señor Presidente, I came to ask for my son’s body. Please, I promise not to retaliate. I just want to see him and say goodbye.” I imagine their eyes watering as they spoke, their glasses a temporal wall concealing their distrust of each other. I picture them as boys, bright beyond the confines of their island, eating mangos on the side of the road, the trails of juice drying on their arms as they watch the cars speed by on the big road that leads to the sea in Puerto Plata. Two boys who would end up on opposite sides of their island’s history.

That day, Abuelo walked out of the palace without answers but with a promise of a thorough investigation into the disappearance, a promise both men knew was a lie.

Growing up without pictures of Papi fast-tracked my forgetting. You gave away all the slides of photos he took—mostly documenting our family’s celebrations and his trips out in nature—to el limpiabotas, the young boy who came to shine our leather shoes once a month in front of our home in Santiago. On the sidewalk, single file, our school shoes and several pairs of your pointed-toe pumps, next to a cardboard box filled with physical evidence of Papi’s sensibility. It eluded me why you felt that his photos outside our home, in the trash or in the hands of strangers, seemed more harmless than tucked away in a closet. Meanwhile, inside our home, large portraits of you hung on the walls, akin to those grandiose photos of communist leaders. The same size of the oil paintings of himself Trujillo forced el pueblo to buy and hang in their homes, captioned at the bottom in white letters: En esta casa, Trujillo es el jefe.

The absence of Papi’s image as I grew up made the five years we spent together vanish into a single memory: him watching TV late at night on the plaid reclining chair in his bedroom. The inky hues of this recollection show me sitting on his lap, holding a pink-and-white plastic toy iron, trying to plug the small suction cup at the end of the curly cord into the flat part of his bald head.As a child, I explained his disappearance to people with a rehearsed mantra: Papi es el ingeniero que se perdió en el Pico Duarte. I also memorized his achievements, collected from my relatives whom I pestered with my relentless questions. For example, I learned that he was a brilliant engineer who helped build the first cable cars in the Dominican Republic that traveled above the lush treetops in the coastal city of Puerto Plata. These were the facts I knew to be true, until the seventh grade when a boy in my social studies class asked out loud if my father was the man killed by Balaguer’s government in the Pico Duarte, setting off the first bout of anger I would direct toward you for concealing the truth from me.

Abuelo spent all his adult life until his death in San José de las Matas, a small verdant city southwest of Santiago, where he was the town’s only doctor. When he studied medicine in la UASD in 1930, only a handful of Dominicans had graduated college on the island. The only medical textbooks available en la isla were written in French, meaning Abuelo had to learn a whole new language before he could study medicine. This persistence in obtaining an education against the odds was something he instilled in and also admired in Papi, an engineer, a college teacher, and his only son.

As a child, I explained his disappearance to people with a rehearsed mantra.

If you visit San José de las Matas today, you can find a bust of Abuelo in one of the city’s plazas, his face immortalized in white plaster with his name engraved below it: Dr. Rafael Morillo Burgos. Everyone remembers him for being the doctor who never took a penny from any of his patients. His medical practice was entirely pro bono, and the bust sits as a testament to the town’s gratitude. But the smaller, seemingly insignificant things Abuelo is remembered for are the ones I hold most tender. One of them was the projectile force and quickness of his injections, followed by the swift swipe of a cotton ball doused in alcohol. One second and no warning. Old school. Another was his disheveled appearance and the perpetually open zipper on his pants, probably due to the garments being ancient—Abuelo vehemently refused to spend money on things he considered frivolous. When his patients pointed out that his fly was open, he would pretend to be mad and reprimand them for looking at his crotch, chuckling to himself as they apologized for the intrusion.

But the one thing I hold closest, the one aspect that is evidenced in my body, is Abuelo’s dark skin—which I inherited only mildly due to your whiteness. The cinnamon of his skin was given to us by his mother, Teolinda, who was Haitian. Between your teeth, you mentioned her to me only once, almost inaudibly, like a shush. Yet, I want you to know that my great-grandmother is permanently lodged in the single curl at the nape of my neck, in the concave space behind my ears. You never informed me of my darkness unless it was a reprimand. “Saliste morena a los Morillo,” you would say, not milky white like the Echavarrías from your side.

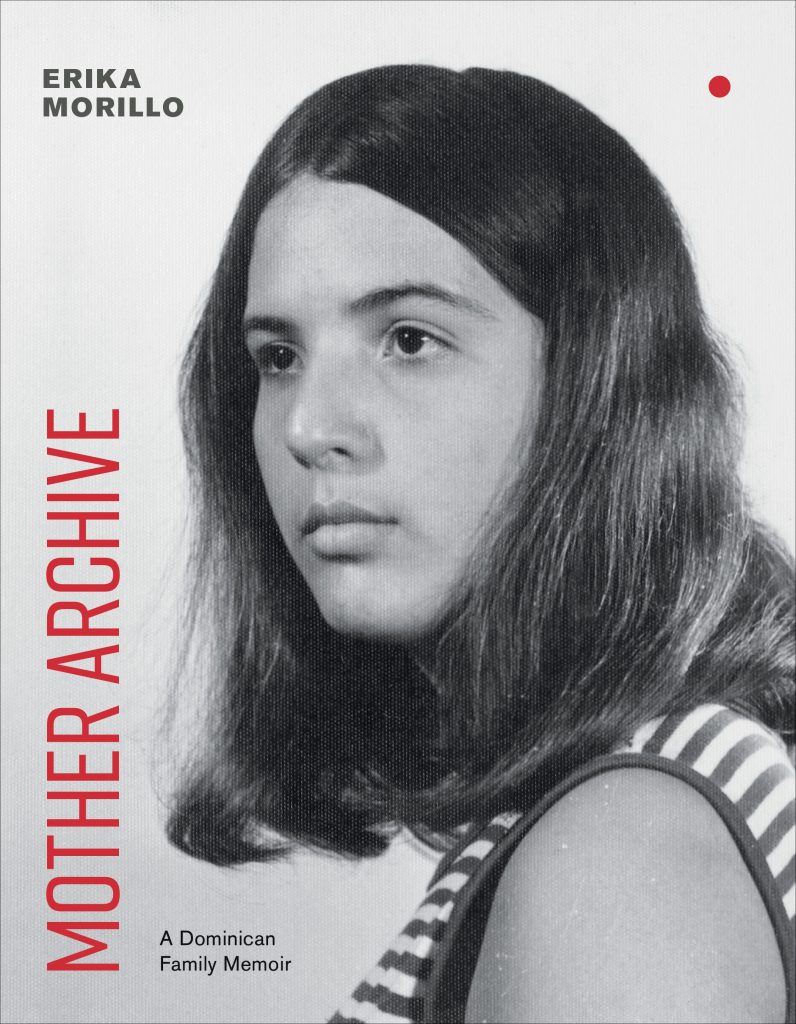

As soon as I turned two and my hair began growing into tighter curls, you started diligently swiping these traces of blackness out of me. My short brown curls in that photograph on my second birthday were straightened with bottles of coconut oil you got from the countryside and the scorching heat of the blow-dryer. In the surviving pictures of my childhood, I sport buzz cuts until the age of five, your answer for getting rid of el pelo malo to make room for el pelo bueno. In one of these photographs, a studio portrait of me, I’m wearing a blue linen dress you made after studying royal children in magazines from Spain. My hair is shiny with oil and heated into a perfect bowl cut, the crown you concocted for me. The girl in this photograph, your vision of beauty.

Later on, when I turned fifteen, you took me to the salón and gifted me your same peroxide-blonde highlights as a birthday present and arranged a studio portrait session at the mall in Santo Domingo. I had asked for a party for mis quince, but you gave me the portrait session with you instead. In the photos, I am wearing a champagne-colored dress that you chose for me. You asked the hairstylist to fashion my hair after yours, a stiff updo parted to the side and sticky with hairspray. The photographer gave me a bouquet of white plastic flowers to hold while you held me against the marbled blue studio background. We, an artifice from head to toe.

I know you did this lovingly, that making me look like you was your way of protecting me. How, en la isla, the vision of progress and sense of worth parents give to their children is often linked to identifying our

white bloodlines, looking for nuestros ancestros españoles in our last names, in our skin, in the shape of our nose. But I’d like to remind you, lovingly, that beyond the fading sensations of my bleached and burned scalp, I am still Teolinda’s great-granddaughter. Still black behind my ears. Still negra.

The one thing I hold closest, the one aspect that is evidenced in my body, is Abuelo’s dark skin.

Abuelo had been watering a bed of pink flowers in front of his home in San José de las Matas when a stranger approached him. It had been five years since his meeting with Balaguer, since Papi’s disappearance. Abuelo folded the green hose over itself to stop the water from leaking, giving the man his undivided attention. A retired military man, he had come to speak to Abuelo about what happened to Papi that January day in 1988 in the Pico Duarte. Cancer had taken over the man’s health, but what he kept quiet seemed to be killing him faster.

In the version we’ve known our whole lives of Papi’s last moments, he was hiking to the summit of the mountain with my brothers and a group of his friends when he felt lightheaded and decided to stay behind and rest for a moment. That was the last time anyone in my family ever saw him. But in the version the man told Abuelo, Papi woke up from his nap disoriented and took another route to the summit. On this detour, he encountered something he shouldn’t have seen, something being performed by military men in the mountains. His Minolta camera strapped across his chest—landscape photography was a favorite pastime of his—gave the wrongful impression that he was there to gather evidence. They hit him with the butt of a gun, only once at first, then repeatedly to get him to confess to things he had no knowledge of. They transported him, bruised and unconscious, to the military base of San Isidro, and when he died from his injuries a few days later, they tucked his body in a barrel and threw it into the sea. The man, who had been stationed at San Isidro at the time, had seen everything firsthand except what happened in the mountains, information the rest of the brigade kept from him. From inside Abuelo’s house, our family watched the two men speak their soundless words from the distance, from one dying man to another.

A few days before Abuelo died, he called me to his bedside and handed me a clear bag filled with coins. The air trapped under its tight knot shaped the bag like a balloon, like the temporary homes fish inhabit on their way out of the pet store. His throat cancer impeded him from speaking clearly, so I put my ear over his warm breath and heard him whisper, “Erika, I dreamt you were in danger and needed to make a phone call but didn’t have any coins to use the telephone. I want to give you these coins, to make sure you’ll always be able to get help.” The room was warm, and the small white table fan carried the cinnamon of his skin to my nostrils. He quickly fell asleep. His hands, dark and fragile over mine. The bag of coins, now so heavy on my lap.

What Papi saw still remains a mystery. Eyes closed, I try to imagine what he saw in those mountains that cost him his life, but no images come to mind. Only a gaping black void. An empty space that now as an adult, I fill with everything I fear. With the light brown mole on my nose that I obsessively check to see if it’s cancerous; with the thought of Amaru going to college and keeping in touch only seldomly like American kids do when they leave home; with the ceiling lights in my kitchen that, despite the extensive electrical work that has been performed, still keep flickering.

Sound itself can be a form of violence, but silence can be the most violent of all.

I make sense of his void by imagining him. The clothes he was wearing when he was last seen: blue jeans, walking sneakers, a red polo shirt. On his wrist, a Bulova watch with black leather straps, with his birth date engraved on the round golden caseback, a gift from Tía M in Nueva York. I imagine the shades of rust that metal collects when submerged in seawater. Concrete is heavy, but the round watch is light and levitates away from the skin, and what will later become tendrils of moss starts out as tiny bubbles filling the space between his skin and the levitating watch. A floating circle resting on smaller ones, the geometry of my pain. I imagine the possibilities that can happen in the span of the two seconds it takes to hit someone with the butt of a gun and leave him unconscious. In the span of un golpe seco.

Two seconds. I replace the blow with the sound of Papi’s sneeze, with a sprinkling of sugar over my grapefruit, his way of getting me to eat it. Two seconds. Fat drops of tropical rain filling my inflatable plastic pool in our backyard, the clean slash of his machete cutting through coconut husk before turning it upside down to fill my glass, white speckles of coconut meat floating in the cloudy water.

Sound itself can be a form of violence, but silence can be the most violent of all. A void that continues to kill after death. I now think of my chanting for Balaguer during those days of campaigning as your strange legacy of silence, how the women in our family have been either silent or silenced. En la isla, a man’s mouth still the main instrument to inform, to legitimize, to kill.

From Mother Archive by Erika Morillo. Copyright © 2024 by Erika Morillo. All rights reserved. Published with permission of University of Iowa Press.

Read the original article here