Have you ever read a story about women that was so horrible and so fantastic it made you cringe? Did you cringe because the story depicted a latent female horror, something that could emerge from the seams of our present moment, yet is packaged as fabrication?

You may have been reading a work of speculative feminism. This genre captures feminist truths in the guise of alternate worlds, magical settings, and fantastical plots. Margaret Atwood claimed the speculative genre should explore a future that is possible from our present reality, something that could happen, but which has not yet occurred. Since the time of The Handmaid’s Tale, the definition of the genre has evolved into a super category to define anything that departs from an imitation of reality.

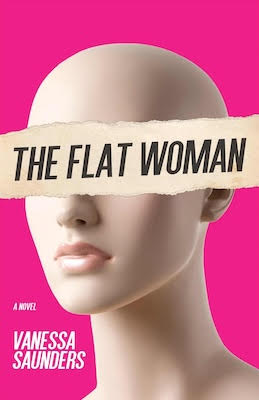

My novel The Flat Woman moves between the magical and the mundane in a world on the brink of ecological devastation. In a world very much like our own, the natural world of The Flat Woman is just starting to deal with the effects of climate change. Instead of taking responsibility, the government has held women exclusively responsible. When a young woman begins a relationship with an environmental activist, she begins to question her detachment from the issues that matter.

When combined with feminism, these stories can amplify concerns about women’s rights. The presence of the unusual—whether that be magic, another world, or elements of fantasy— can turn our understanding of feminism on its head. Here are 7 trail-blazing books of feminist fantasy:

Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler

Published in 1993, this novel takes place in California in 2024 against the backdrop of environmental failure. Sound familiar? The story centers around an eighteen-year-old named Lauren Olamina who suffers from a syndrome called hyper empathy, meaning she can feel the physical pain of others. Unfortunately, she lives in a world where people are constantly hurting.

Written in epistolary form, the story documents Lauren’s journey from California to Oregon as she forms her own religion, Earthseed, among a community of the displaced. Known as the mother of Afrofuturism, Octavia Butler wrote this story from the point of view of a young Black woman at a time when very few women of color were represented in science fiction.

Get In Trouble by Kelly Link

A Pulitzer Prize finalist, this book of short stories is delightfully strange. According to Kelly Link, this collection was named after the characters who populate its pages: possessing poor impulse control, these characters all have the tendency to get into trouble. But these stories are not solely surprising on the grounds of their behavior. These nine stories frequently blur genre boundaries, subverting the reader’s expectations.

In “Two Houses,” six astronauts tell each other ghost stories. In “The New Boyfriend,” a high school girl falls in love with a friend’s birthday present: a ghost boyfriend. In “Light,” a woman’s husband leaves her for a pocket universe. These stories channel the dreamy, romance of late adolescence. They remind the reader that the interior lives of teenage girls are just as an important source of high literature as stories about middle-aged men.

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

Set in the undetermined future, in The Left Hand of Darkness, a human envoy named Genly ventures to a different planet whose inhabitants are biologically androgynous for most of the year. At the core of the story is Genly’s relationship with Estraven, a diplomat who tries to help Genly gain acceptance in this foreign land.

The novel is structured as a series of documents penned by Genly and Estraven as well as myths and legends of the imagined world. Some of the narrative friction comes from the sharp juxtapositions of the styles of the different documents, which demonstrates how digressions are an effective narrative engine. Some of Le Guin’s best writing describes the scenery of this distant planet, especially in the second half of the book where the story of Genly and Estraven reaches its full pitch.

Ripe by Sarah Rose Etter

What if you were born with a black hole floating above your head? What if you worked at a soul-crushing tech job that barely pays you enough to make rent? Meet Cassie, the protagonist of Ripe. As Cassie navigates a life in San Francisco, Sarah Rose Etter shows us a world that is both hyper real and endlessly strange. The story explores the intersection of the marvelous and the mundane in vivid imagery. Despite the oddness of the magic, the depiction of a lonely woman’s slow burn-out in a soulless city is extremely relatable. This is a story driven less by plot than by ideas—one woman’s slow suffocation under the burden of late-stage capitalism is a searing indictment of America’s toxic work culture.

Sultana’s Dream by Royeka Hossain

Sultana’s Dream contains two works of short fiction published in 1905 by Royeka Hossain, a self-educated Bengali writer and a pioneer of science fiction. The standout piece from this collection is the titular short story, a work of feminist utopia which describes a world where men are confined to the domestic sphere and women, literally, run the world. Formed as a philosophical dialogue between two characters, the story is structured in a Socratic seminar style. The fourteen-page story shows us what the world is by showing us what the world could be. On the way, Hossain implements a unique visual language, which memorializes the world through its unique technology, such as flying cars and solar-powered kitchens.

“Padmarag,” the other text in the collection, depicts a feminist utopia like Sultana’s Dream, though it stays within the confines of literary realism. The novella illustrates the world of an Indian women-run school and welfare center. The setting for this novella is no surprise considering the author’s real-life passion for educating women, illustrated in the school for girls Hossain founded in Kolkata.

House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

House of the Spirits is a feminist, socialist work of magical realism. Modeled after Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Isabel Allende’s novel follows four generations of the Trueba family in post-colonial Chile. Some of the book’s characters are thought to be based on real-life figures, such as Salvador Allende, a prominent Chilean socialist, and former president, as well as Pablo Neruda, poet and senator of the Chilean communist party.

This book blends a story of a country’s history with the story of a family, focusing on the magical and the fantastic like One Hundred Years of Solitude. But, unlike its predecessor, House of the Spirits focuses on the relationships between women: mother and daughter, sisters-in-law, and grandmother and granddaughter. Using a roving, omniscient point-of-review, the book highlights the impact of toxic masculinity on the women of the Trueba family.

The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter

This book of short stories retells the fairy tales you remember from your childhood, but not as you remember them. Unlike the sanitized Disney adaptations, the ten stories in this collection are laced with violence, gore, and sex. The standout story from the collection is the novella titled “The Bloody Chamber,” a retelling of Bluebeard that revises the story to be spooky, atmospheric, and surreal. A truly important feminist revision, this book intentionally reframes the original fairy tales to emphasize the horror and misogyny latent in 17th through the 19th century storytelling.

Read the original article here