In this May 5, 2020, file photo released by Xinhua News Agency, China’s new large carrier rocket Long March 5B blasts off from the Wenchang Space Launch Center in southern China’s Hainan Province.

Tu Haichao | Xinhua | AP

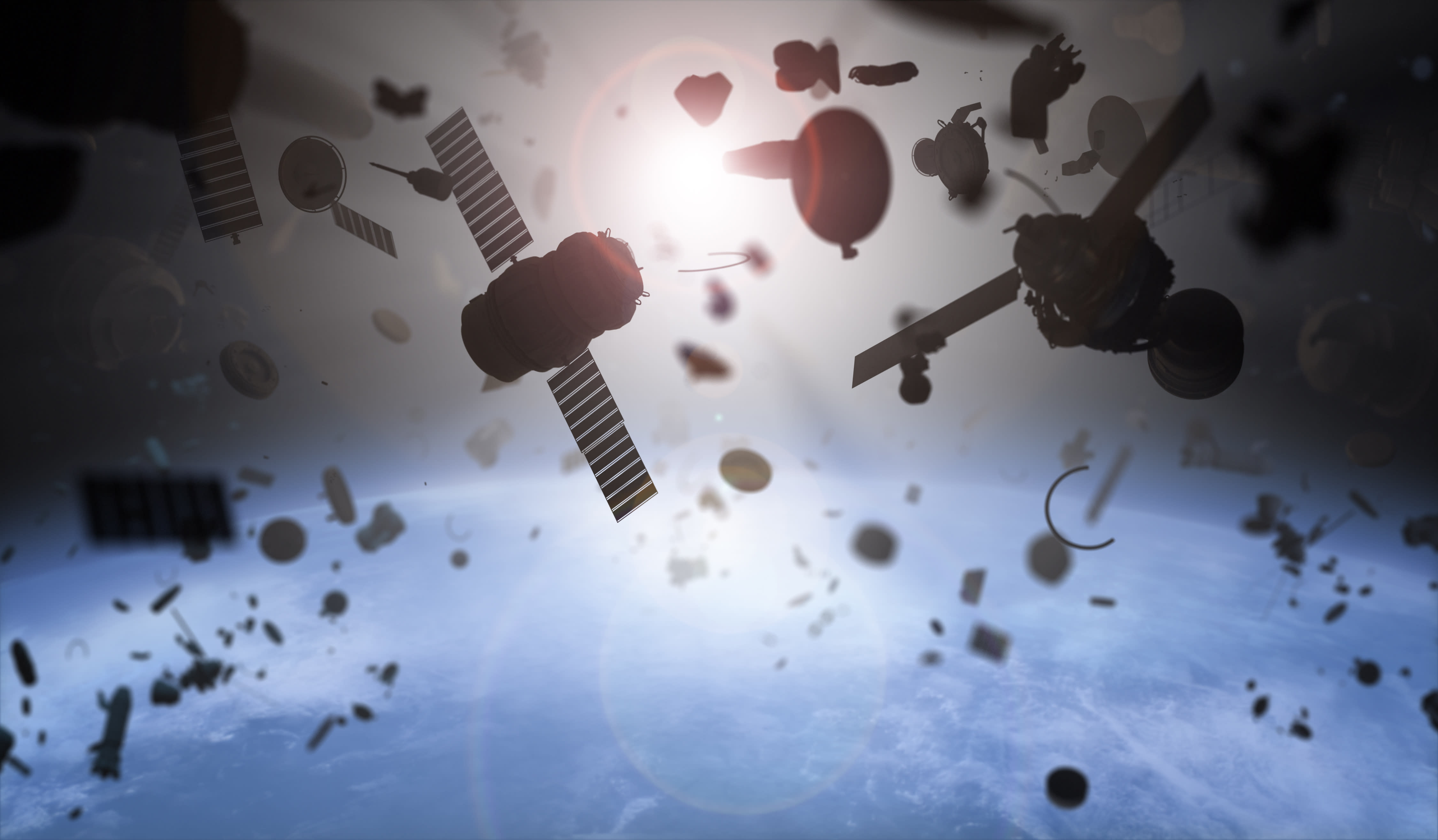

Since humans first went up in space in 1961, we’ve done a poor job of keeping it clean. NASA currently estimates that there are some 21,000 pieces of space junk larger than a softball orbiting the Earth and 500,000 pieces of debris the size of a marble or larger. Since the debris travels at speeds of up to 17,500 mph, they could damage a satellite or spacecraft.

Just last week an 18-ton Chinese rocket passed over Los Angeles and New York City’s Central Park before falling into the Atlantic Ocean.

The estimated 8,800 tons of objects that humans have left in space are becoming a danger. Near misses are common these days. Last September there was one between Elon Musk’s SpaceX satellite and one from the European Space Agency.

But so far, there has been just one major collision: In 2009 American satellite Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251, a Russian satellite, crashed, destroying both over northern Siberia.

In January a satellite run by AT&T‘s DirecTV was found to be in danger of exploding and needed to be moved or else it could harm other satellites. Since that time, no action has been taken. Meanwhile, in late April the FCC voted to require more disclosures from satellite operators seeking licenses but declined to introduce any new laws governing the removal of orbital debris.

Companies rush to address the problem

According to experts, the problem is projected to get worse. By 2025 as many as 1,100 satellites could be launching each year. The number of satellites orbiting Earth is projected to quadruple over the next decade.

Astroscale, one of the few companies whose mission is to clean up such space debris, is leading the charge to clean up our space pathways and avoid collisions among the objects that humans recently have left in space. The Japanese company is currently working with Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to carry out the agency’s Commercial Removal of Debris Demonstration (CRD2) project.

Kanae Kobori, an engineer with Japanese space start-up company Astroscale, demonstrates pulling a magnet off of a piece of steel during the 35th Space Symposium at The Broadmoor in Colorado Springs, Colorado on April 9, 2019.

Jason Connolly | AFP | Getty Images

The JAXA mission plans to complete its first phase by the end of 2022. The goal of the mission is to launch a satellite that will observe and acquire data on the rocket upper stage that the second phase will seek to deorbit. The idea is to find out how the debris moves in space and set up a safe and successful removal.

Astroscale is not alone in seeking to clean up space debris. Northrop Grumman last year launched its first Mission Extension Vehicle spacecraft (MEV-1) to prove it could intercept falling satellites, repair them, remove them from traffic and put them back in orbit.

Swiss start-up ClearSpace, meanwhile, has a more specific goal: to remove a 100kg Vega Secondary Payload Adapter (Vespa) upper-stage rocket orbiting around 400 miles above Earth. It plans to do that in 2025.

Petrovich9 | Getty Images

A NASA spokesperson noted that solving the issue will take cooperation between nations. “The remediation of the near-Earth space environment will necessarily involve not only a multi-agency approach but an international effort,” said J.D. Harrington, public affairs officer at NASA. Harrington estimated that the U.S. was responsible for less than a third of all the detritus.

Tom Wilson, vice president of Northrop Grumman space systems, said the company is pioneering the market for in-space satellite servicing and logistics services with its Mission Extension Vehicle. “Our efforts are driven by our customers’ needs to protect their space assets,” he said. “MEV provides a roadmap for a broader range of servicing,” he said.

Lockheed Martin has also announced the construction of a Space Fence on the Marshall Islands to track and identify space objects.

U.S. Air Force’s Space Fence under construction on Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

Source: Lockheed Martin

Dr. Holger Krag, head of the Space Safety Programme Office at the European Space Agency, said the agency is looking into using lasers to gently push the objects off the path. “So far, every year, humanity leaves dozens of objects behind in orbit without disposing of them. This is either because disposal was not foreseen or did not work, or the contact to the spacecraft was lost. This number is far too high,” said Krag.

Chris Blackerby, group COO and director, Japan for Astroscale, said awareness is rising that there is too much junk in the Earth’s orbit. “I think the idea that space debris is an active threat to our current satellite population is becoming more widely accepted,” said Blackerby.

Another worry is the Kessler Syndrome, in which NASA scientist Donald Kessler proposed that an exploding chain of space debris can make exploring space and the use of satellites impossible for generations. “The fear is that we get to a level of unsustainability of orbit,” Blackerby said.