Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

Behind so many writers and thinkers, there has been a supporter, editor, typesetter, listener, advisor, child-rearer, cleaner, cook, and lover.

Many writers’ spouses have influenced or made possible the great books we still read today. Some, it’s true, have not been quite so helpful. Below are glimpses of a few relationships, ranging from the indispensable to the disastrous.

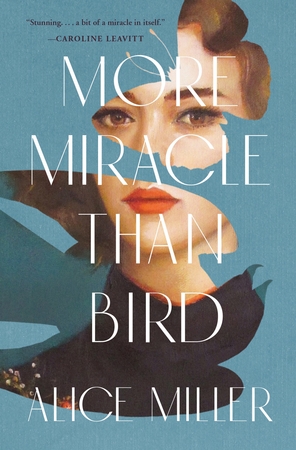

In this list you’ll find Georgie Hyde-Lees, the subject of my first novel, More Miracle than Bird. Brilliant and independent, Georgie worked in a war hospital in First World War London, had very unusual ideas about death, and took extraordinary actions to enact those ideas. But the main reason we remember Georgie’s name now is because she ended up marrying one of the most famous poets of the twentieth century, W.B. Yeats. Theirs is one of the strangest love stories I’ve ever heard.

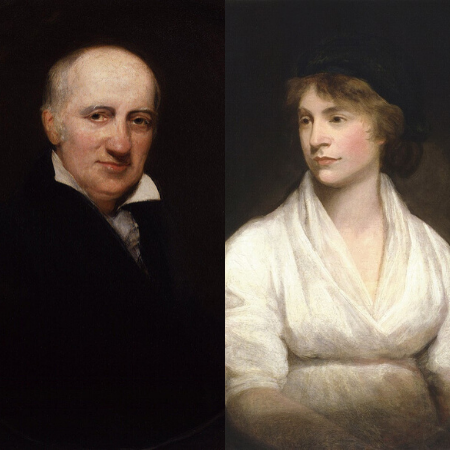

William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, 1797

Cut short by Mary Wollstonecraft’s early death (after giving birth to the couple’s daughter Mary, who would one day write Frankenstein), this relationship was remarkable for being so modern. In fact, the partnership of these two philosophers would be the model for Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s relationship more than a century later.

Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin’s friends thought they were mad for maintaining two different households after they were married. Every morning William walked to his office and read and wrote until 1pm on his own, and Mary stayed at home and wrote herself. While both parties were happy with this arrangement, Mary found that as she was the one at home, far more of the domestic tasks were left to her. At the time it was unheard of to suggest that her writing time might be as important as his, even though Mary had already published several books, including A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. While William and Mary agreed on the equal importance of their work, the imbalance of domestic tasks was never resolved. Still, when their relative independence worked, it worked well. “I wish you, for my soul, to be riveted in my heart,” Mary wrote, “but I do not desire to have you always at my elbow.”

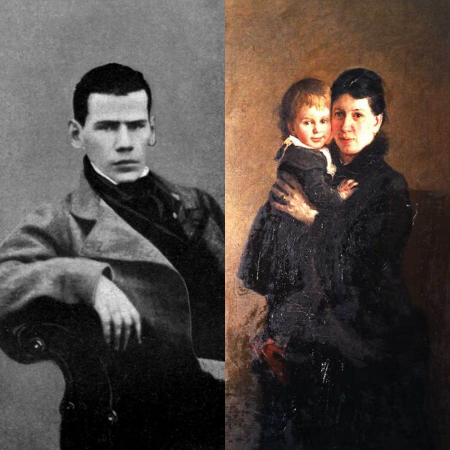

Count Leo Tolstoy and Countess Sofia Tolstoy (née Behrs), 1862-1910

Determined to be entirely honest, 34-year-old Count Leo Tolstoy gave the 18-year-old Sofia Behrs all his diaries to read in the week between his proposal and their marriage. Sofia was extremely upset by the revelations in these diaries, particularly on reading of Leo’s early exploits with peasant girls. Still, the couple read each other’s diaries for their entire marriage, only stopping in the final year of Leo’s life where he controversially vowed to keep a diary for himself only. Over the course of the marriage, Sofia raised their 13 children, copied out his voluminous works many times over, and despite being married to one of the most famous men in the world, was left nothing when her husband died because he did not believe in property or copyright. In Leo’s diary from 1897, he wrote: “So[fia] has read this diary in my absence and is very distressed that people might afterwards conclude from it that she was a very bad wife.” The year after, one of Sofia’s diary entries reads:

“I was wondering today why there were no women writers, artists or composers of genius. It’s because all the passion and abilities of an energetic woman are consumed by her family, love, her husband – and especially her children. Her other abilities are not developed, they remain embryonic and atrophy. When she has finished bearing and educating her children her artistic needs awaken, but by then it’s too late.”

Elizabeth Lilith Plaatje (née M’Belle) and Solomon “Sol” Plaatje, 1898-1932

This couple struggled to understand one another at first. Despite the fact they both spoke several languages, he did not understand her Xosa and she only understood some of his Setswana. In their South African context, this caused problems beyond just communication; as Sol observed:

“My people resented the idea of my marrying a girl who spoke a language which… had clicks in it; while her people likewise abominated the idea of giving their daughter in marriage to a fellow who spoke a language so imperfect as to be without any clicks.”

Instead the couple read Romeo and Juliet together, and Sol quipped that their ability to converse in English was the only thing that saved them from “a double tragedy in a cemetery.”

Elizabeth was a teacher and her husband liked to point out that she was the better educated of the pair. As members of the small African elite in South Africa, both Elizabeth and her husband sought equal rights for African people and inclusion in the broader British context. Sol was a novelist, journalist, politician, and a founding member of what would become the African National Congress. He traveled abroad a great deal for his work, during which time Elizabeth had to sell their house and move in with her brother in order to keep the family safe and solvent. Throughout his life, Sol was continually struggling for recognition, publishers, and the means to support his family, and these concerns plagued him up until his death from pneumonia in 1932. Although Elizabeth outlived him by a decade, it was not until the 1970s that her husband was recognized as a leading figure in South African history.

Virginia Woolf (née Stephen) and Leonard Woolf, 1912-1941

Reporting the news of her marriage, the 30-year old Virginia Stephen announced: “I’ve got a confession to make. I’m going to marry Leonard Woolf. He’s a penniless Jew. I’m more happy than anyone ever said was possible.” Of the marriage itself, she wrote that they both wanted “a marriage that is a tremendous living thing, always alive, always hot, not dead and easy in parts as most marriages are. We ask a great deal of life, don’t we?” The marriage was not without obstacles; there were sexual problems from the beginning. The Woolfs wanted to have children but were advised against it because of what was referred to as Virginia’s “mental instability.” Over the course of their marriage, Leonard would help Virginia through multiple bouts of depression and numerous suicide attempts. For some years, Virginia had an affair with Vita Sackville-West with Leonard’s blessing.

In 1917, the couple set up the Hogarth Press—publishing Virginia’s novels as well as works by T.S. Eliot, Katherine Mansfield, and Sigmund Freud—and Leonard wrote in a letter: “I should never do anything else, you cannot think how exciting, soothing, ennobling and satisfying it is.” A writer, publisher, and former colonial administrator, Leonard appeared content at the end of his life that he would be remembered as Virginia’s husband. Virginia famously wrote in her suicide note in 1941: “What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good . . . I don’t think two people could have been happier.”

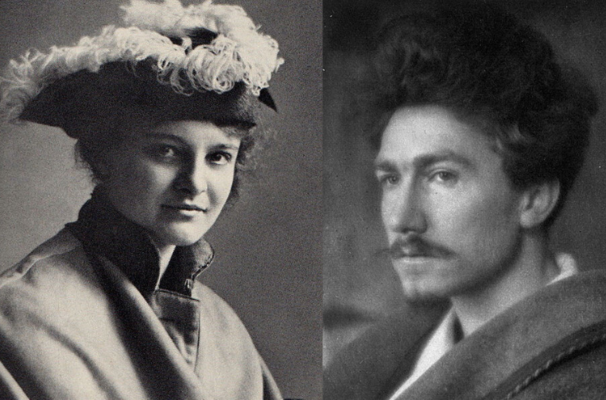

Dorothy Pound (née Shakespear) and Ezra Pound, 1914-1973

“I feel quite sure,” the Irish poet W. B. Yeats wrote in 1915, “that Ezra & his wife who are obviously devoted must have fallen in love out of sheer surprise & bewilderment.” Dorothy, an English painter, met the American poet in 1909 in London, where she fell for him, and he fell for her and her set—Dorothy’s mother was the great friend and former lover of W.B. Yeats, the very man that Ezra had crossed the Atlantic to meet. After Dorothy married Ezra in 1914, they stayed in England for the war, before moving to Paris where Ezra finally enjoyed the adulation and fame he had sought.

In 1924 Ezra began an affair with the classical pianist Olga Rudge, and they had a daughter. Their affair would last for 50 years. While Ezra’s infidelity was well-known, Dorothy’s response was a dignified silence. Dorothy stayed with her husband, moving to Italy, and giving birth to a son, who was sent back to England to be raised by Dorothy’s mother. Around this time Ezra was also fostering another devotion, to Mussolini, fascism, and anti-Semitism. After he was arrested for his pro-Mussolini broadcasts, he was taken back to the United States and declared insane. Dorothy moved to Washington and tended to Ezra, his needs, and his papers, until his release from St Elizabeth’s twelve years later. Ezra briefly hoped to marry one of the students from what he called his “Ezuversity,” despite her being nearly 50 years his junior. It was around 1960 that Dorothy and Ezra parted for good. Ezra spent the last decade of his life with Olga, and Dorothy and Ezra never met again. In 1971, Dorothy published a book of her own watercolors and drawings, and she died the year after Ezra, in 1973.

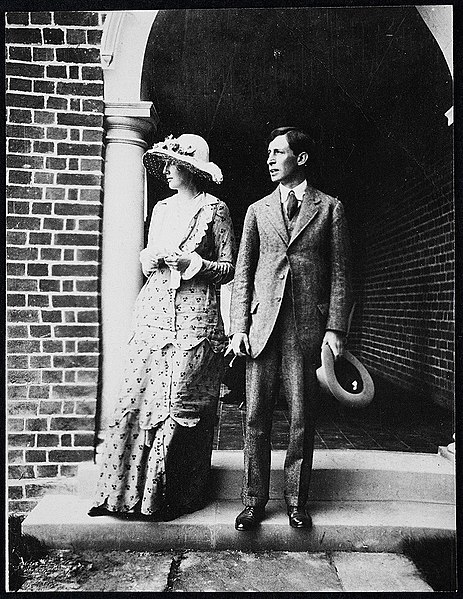

Georgie “George” Yeats (née Hyde-Lees) and William Butler Yeats, 1917-1939

When Georgie Hyde-Lees and W.B. Yeats married, the public laughed. Here was Willy Yeats, a famous poet at 53, who had spent many decades publicly mooning over—and being rejected by—the beauty, actress, and heiress Maud Gonne. Now, finally realising he’d never had a chance with Maud, he’d found himself a 25-year-old (“rich of course” one man quipped) and agreed to marry her. Although the beginning of the relationship was very difficult—and provides some subject for my upcoming novel—the marriage went on to last for more than twenty years.

Georgie, known as George after her marriage, raised their two children in a medieval tower with no electricity or running water. When Willy Yeats died in 1939, Georgie was still only 46, but in a way, her task as the poet’s wife was only half complete. Known to be brilliant but a very infrequent letter writer, she received a letter from Ezra Pound demanding: ‘Wot the hell Do yu do with yr mind?’ Many people urged George to write a book about Yeats but instead she continued quietly in her role at the helm of what she called “the Yeats industry,” dealing with the poets’ extensive works and assisting the streams of academics arriving to study him. When she was struggling with this role, the Irish writer Frank O’Connor wrote to reassure her that this was “the last big job” she would ever do for him. Finally recognised for her contributions, George replied in an unusually emotional note: “That phrase will be in my mind for ever. It is the first time anyone has written such a sentence to me.”

Michelle Cliff and Adrienne Rich, 1976-2012

A year after the Jamaican American writer Michelle Cliff and the Jewish poet Adrienne Rich met in 1975, they became partners for life. Adrienne’s first collection was published in 1951 when she was selected by W.H. Auden for the Yale Younger Poets Prize; Auden famously praised her poems for being “neat and modestly dressed.” As time went on, Adrienne’s poems were criticized by the literary establishment for becoming “strident” and “too personal,” as she began to directly address the plight of women and lesbian existence.

Writing across a wide range of genres, Michelle addressed colonialism and racism in her work. She declared her own creative intention in her 1991 essay “Caliban’s Daughter” to “reject speechlessness” and “to invent my own peculiar speech with which to describe my own peculiar self, to draw together everything I am and have been.” Together and separately, Michelle and Adrienne worked to encourage and amplify repressed voices. In 1981, they became joint editors of the multicultural lesbian journal Sinister Wisdom.

The details of Michelle and Adrienne’s relationship were always kept private. Of her marriage to a man back in the 1950s, Adrienne said: “I married in part because I knew no better way to disconnect from my first family. I wanted what I saw as a full woman’s life, whatever was possible.” After she came out, she noted that “the suppressed lesbian I had been carrying in me since adolescence began to stretch her limbs.” Over the course of Michelle and Adrienne’s relationship, which lasted more than thirty years, Adrienne pursued work, as she put it in one poem “for the relief of the body / and the reconstruction of the mind.” Adrienne died in 2012, and Michelle died four years later.