Electric Lit is 12 years old! Help support the next dozen years by helping us raise $12,000 for 12 years, and get exclusive merch!

I met Rax King outside of a bar on the first truly cold autumn night of the year, for which we both underdressed. We were wearing identical faux-fur lined denim jackets—albeit in different colors—and, weirder still, had both accidentally inflicted minor-but-nagging injuries to the thumbs on our left hands. From there we wound up on the topic of interior decor and affirmed that, although we do both have animal print duvets, they are at least different animal prints.

From there we landed on a new decision/dictum/lifestyle change that Rax recently committed to.

“I’m only going to wear outfits where at least one thing is an animal print, and preferably more than one, and preferably two different animal prints from different animals.”

She continued, “And the night that I made that decision, I spent $200 on used animal print clothing on eBay. And then the next day, I woke up just like, ‘What did I do?’ And then I had like 10 emails, congratulations on your animal print purchase. And then I was kind of regretting it and then everything arrived and I was like, ‘No, this was right. This feels right.’”

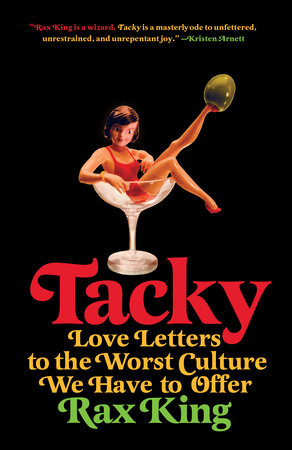

To say Rax demonstrates commitment to the bit here would be to imply that anything Rax does is ever less than completely sincere. As we discuss in our interview below, and as Rax lays out in her remarkable debut essay collection Tacky, the bedrock of tackiness is utter un-selfconscious sincerity. That sincerity might garner ridicule—including, obviously, being labeled “tacky”—but it also leads to a sense of, this feels right. And, sometimes, it also leads to a cool leopard print bedspread.

Rax and I spoke about virtuous shoplifting, identifying the kernel of an essay, “Notes On Camp,” the first-person industrial complex, and of course, Guy Fieri.

Calvin Kasulke: So the subhead of your book is “Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer.” But a lot of the culture you discuss is from your adolescence and coming of age. Why that section of culture?

Rax King: Primarily because it’s personally important to me. I grew up with Creed, I grew up shoplifting from Bath & Body Works, these were formative experiences for me.

As I got a little older, it became obvious that these things I liked so much were not cool at all. Other people, who seemed smarter and more worldly than me, who I really wanted to impress, they did not like any of the same stuff as me. And it was a moment of forced reeducation, like I needed to get on board if I wanted to make friends with the cool smart people—which I did, because I was 16 and shallow.

And after long enough time passed and I was no longer in high school, I felt comfortable revisiting all this stuff I used to like, and it turns out all of it is still awesome. So I was right, everyone else was wrong. You can quote me on that.

CK: What were your shoplifting techniques?

RK: I wasn’t super brave with it most of the time, like—nothing with a security tag. I liked anything I could slip into my purse. I really liked the sample makeups from Sephora and whatnot because it was not only easy to steal them but I also felt pretty virtuous about it, like “This is something nobody else is going to want. It’s got 500 people’s other mouths all over it already, I might as well.”

CK: One of the things that you’re really magnificent at is making small moments feel really resonant. I think the average person telling a similar anecdote would leave their audience feeling like, “That’s it? That’s all? That’s what you were driving at?” but you have a gift for making them land. Do you start with those moments and then build an essay around it, or do you start writing about a thing and stop when you hit one of those moments?

RK: No, the little stuff is usually where I do start actually. I feel like the reason we hear so many of those disappointing anecdotes that fizzle out into some tiny little nothing, is that those moments are important to people. Those moments are the ones that stick, I think. Big picture stuff fuzzes out over time, but I’m always going to remember the color of the tracksuit that my dad wore all the time—stuff like that. The stuff that colors in memories is what I think is most important for coloring in a story.

For the Jersey Shore essay about my father, the thing that I remembered first was him calling me every week when I went off to college to tell me, play by play, what had just happened on Jersey Shore that I had just missed. Which is such a boring thing to describe, but it was really meaningful to me and to him both—and I think that if you try to excavate why something is meaningful, you’ll be able to unlock some of that magic in those tiny little instances.

CK: Your essay about a date you had at the Cheesecake Factory achieves something that’s similarly difficult to convey, because you’re telling a story about an event that was ultimately disappointing and kind of boring. Which, by the way, what is your go-to order at the Cheesecake Factory?

RK: All right, settle in. Gotta get the avocado spring rolls to start—and a mojito, because not everybody has them and the ones at the Cheesecake Factory are huge.

Avocado spring rolls as the starter, the Louisiana chicken pasta as the main, and then at that point, you’re going to want to tap out early and get a box for leftovers. They give you two chicken breast patties and you want to save one, plus a bunch of pasta, because you don’t want to fuck up dessert. Then for dessert, peanut butter fudge ripple cheesecake, usually to go, and then I eat dinner all over again when I get home.

CK: That’s beautiful and perfect. Okay, so I want to try and put together a unified theory of tackiness, and I’ve got a couple of questions to hopefully help us get there. The first one is: Who gets to decide what’s tacky?

RK: So I thought about this a lot in terms of camp actually, because one of the things I read as research was “Notes On Camp.” The way camp is described in the essay is as something fairly ordinary, if over-the-top, that you, the viewer, have a private, extraordinary experience of. You decide that the thing is camp.

And for me, something that is tacky is something that you would decide is campy, but you’re too embarrassed about it. It’s not quite out there enough to be campy or to be kitschy, it’s too ordinary for that. So you’re uncomfortable with liking it and rather than make a big deal over how much you like it, the way people did with The Room—you can’t really do that with Creed. Creed is not quite bad enough to be “so bad it’s good,” so you just bury it deep and then it comes out when you write a collection of personal essays.

CK: It’s the wrong kind of gauche or outré.

RK: Right. It’s something gauche that you don’t think you could get a bunch of people on board with. People get together to go see The Room in theaters, there’s a whole culture of it now. There is no such culture with going to see Creed live to watch Scott [Phillips] play that weird ass song he wrote about the [Miami] Marlins. He wrote a love song to the Marlins.

CK: Why are some people repelled by tackiness and why are some attracted to it?

As I got older, it became obvious that these things I liked were not cool. It was a moment of forced reeducation, like I needed to get on board if I wanted to make friends with the cool smart people.

RK: I think it comes back to being, again, embarrassed. It’s more a statement about yourself, to be repelled by other people’s taste, because if you’re not too self-conscious about it then you like your thing, they like theirs. That comic, “Let people enjoy things,” people are very annoying with it now but it had a point. People should be able to enjoy harmless things—they do their thing, you do yours, everybody’s theoretically happy. I think when it comes down to being repelled by other people’s taste, whether the taste is tacky or gauche or too highbrow, all you’re talking about is yourself.

That repulsion is just a function of something you don’t like about yourself, probably, something that you’ve tried to suppress. I’m honestly a little bit repelled by anything too highbrow—I really have to fight the instinct towards anti-intellectualism in myself. And frankly, it’s because smarty-pants types have been really shitty to me my whole life long, it’s got nothing to do with the stuff they like. It’s all my own insecurities and my problems and the reasons they were shitty to me is probably down to their insecurities and their problems and everybody’s just awful all the time. And I think that the thing to do is to just go your own way and mind your own beeswax.

CK: Is tackiness the providence of femininity?

RK: Maybe less femininity than the high femme as an article of being.

CK: Say more about that.

RK: I think it’s possible to partake of femininity in a fairly highbrow way. Little corduroy skirts and all that Madewell shit. That feels totally feminine, but I also feel like that person has no interest in shotgunning beers with me and listening to Puddle of Mudd—that’s not what I’m going to do with that person, it’s two separate femininities.

Looking back on the relationships that I’ve had with women, both platonic and not, I’m consistently attracted to super high femme types who take like an hour and a half to do their hair every single day, who also love dogshit stuff and aren’t the least bit self-conscious about it. I want to party with that person. That’s a fun person. It’s not the providence of femininity, it’s the providence of doesn’t-give-a-fuck high femmeness.

CK: Do you have any tacky icons personally, or just people who you think are icons of tackiness?

When it comes down to being repelled by other people’s taste, whether the taste is tacky or gauche or too highbrow, all you’re talking about is yourself.

RK: I don’t think you can do much better than Fred Durst. Like him or hate him, he made his vision come true for the entire world. Everybody knew “Nookie,” everybody knew “Break Stuff” for a time. That’s tacky power.

He was just—I’m so sorry Fred Durst if you read Electric Literature for some reason, but you are kind of an ugly motherfucker. And he just showed up leaning into the ugly with that terrible facial hair and the baseball caps and the gym shorts, not giving a shit, essentially in fuckboy drag, and people were into it for a short time. He did that. He made that happen for folks. I think that’s a tacky icon for me.

DJ Pauly D from Jersey Shore I would say has a similar, not that self-aware vibe. I guess at this point he’s been making money off that persona for so long he’s got to be much more self-aware than when he first got started—but that hair, and the gold chains, the Ed Hardy, I was like, “Sign me up. This guy is leaning in.”

CK: For some of the people you’re listing also it feels sort of compulsive, it feels like it’s more than sincerity. It feels like they couldn’t stop if they wanted to.

RK: I think that’s important actually. Tackiness, even when it’s diametrically opposed to your own self interest, you can’t stop. Fred Durst cannot stop Durst-ing. He’s going to be that guy until the day he dies. He’s kind of trying to pretend he was always in on the joke now and nobody buys it because we’re all like, “We have affection for you now. Enough time has passed. But come on, you were that guy, you were the guy who didn’t understand why we were laughing.”

I think that at this point, enough people look at me as a person with a compulsion that I’m pretty safe in it now. Nobody thinks I’m doing a bit anymore. For years and years, all I’ve talked about is the disappointing dudes I’ve had sex with and weird conversations with neighbors and the very mundane but also out there shit that happens in the course of a day. And there was a stretch when everyone was like, “You’re making this up for retweets.” And then it just kept going and they were like, “Oh no, she’s a diseased person. Something’s not right.” And they’re right, something isn’t.

CK: Speaking of, you post a lot of autobiographical tweets that are fairly personal, and now you have a collection of personal essays. Did you grapple at all with having an extant semi-public persona, and then writing a book that was going to augment or contrast that persona in some way?

RK: I developed this paranoia that there would be a weirdo, and that weirdo was going to go through everything I’ve ever tweeted in my time on the internet and then cross-check it against my book and find one discrepancy, maybe. And somehow that weirdo and that discrepancy were going to ruin my life. And I don’t even think it exists and I don’t think anybody’s paying that much attention to me, but it’s sort of the process of turning the matter of your existence into content.

I’m consistently attracted to super high femme types who take like an hour and a half to do their hair every single day, who also love dogshit stuff and aren’t the least bit self-conscious about it. I want to party with that person.

The memory is a stupid thing and you’re going to get stuff wrong once in a while, you’re going to harp on stuff until people wonder why you don’t talk about anything else. It becomes a little more personal, I think, than when you’re writing fiction. So I feel very exposed a lot of the time and I have to take steps to make sure the things I write don’t feel extractive to me, because that’s the big gripe that everyone has with personal essays—it’s the lowest paid form of media writing but it takes the highest toll on the person writing it, theoretically.

I’ve never really found that to be the case, it doesn’t necessarily take a toll on me to write about myself, but to have it all come out in a cluster like this, a dozen personal essays—plus I’m tweeting all the time because I’m a diseased person—it’s just a lot of content about myself for people to pick at, should they want to do so. I just have to cross my fingers and hope that nobody’s paying attention to me that closely.

CK: Your James Beard-nominated essay about Guy Fieri ends the collection. Why did you choose that essay as the finale?

RK: I just think it’s one of the prettiest things I ever wrote. I’m very proud of it. I want to go out on a high note so that if somebody hates the rest of the book, they will hate it less. I hope.

CK: Why do you think that essay resonates with so many people?

RK: I wish I knew. Obviously a lot of people have been in abuse situations themselves. And obviously Guy Fieri has a lot of fans. So I guess I just captured the little crossover circle of the Venn diagram. But it’s not just that, because people are really devoted to it in a way that always surprises me. Every time I post it, it goes viral. And I don’t know, to toot my own horn a little, I do think it’s a good piece of writing, but people are much more into it than I expected when I published it. So I’m always just like, “Yeah, good for you, Rax.”

CK: Are there any essays that almost made the cut that you dropped or that you didn’t finish writing?

RK: Yeah, there was one about blowjobs—like very explicitly about blowjobs—that I wound up cutting and publishing on my Patreon instead. And I’m really glad I did because in the course of recording my audiobook, I realized that I have six essays explicitly about sex all in a little cluster, all in the middle. And it was just like me reading out loud to this very pleasant, very polite sound guy, and we were the only two people in the room, and I don’t think I could have gotten much more explicit without wanting to blow my brains out. So that one didn’t make the cut, and I’m glad.

CK: You saved yourself from having to get extremely, extremely explicit with the sound guy.

RK: In that essay, I referenced a now-defunct porn website called “milk my cock,” and I don’t think I could say the phrase “milk my cock” to a stranger. It’s too much. I have my limits.

CK: Is there anything you’re surprised people have been asking you about over the course of your interviews and events so far?

RK: I guess I was expecting to end up talking more about sex. It comes up so often in the collection, to the point that people on Goodreads are mad at me. They’re like, “This book has too much sex,” and I’m like, “You’re telling me? Buddy, that’s my life that we’re talking about. Absolutely, it has too much sex,” but it just hasn’t come up once. People mostly want to talk about Creed and my dad. And Guy Fieri.

My surprise isn’t just because there’s so much sex in the collection, because whatever, we’re all adults. But for me, sex is kind of the ultimate tacky thing. It’s largely unmentionable, you’re not supposed to have too much of it, you’re certainly not supposed to talk about it in mixed company. So in that way, it is much like Creed.

For me the connection is inextricable between sex and the weird little relationships that I’ve had with various pop culture franchises. One informs the other, inextricably. And it just hasn’t come up and I’m like “Okay, that’s fine, let’s all be comfortable,” but it is surprising.

CK: Were any of those essays difficult to write?

RK: There’s an essay in the book about an affair that I had with a married dude. And that was recent enough that it was still somewhat raw when I was writing it. I was still so pissed off, so angry. But most of the time, sex isn’t really fraught for me. I’ve had enough of it and much of it just friendly like, you shake someone’s hand, you have sex with them, it’s normal. But anything where there’s unfinished feelings business? It felt like summoning a demon to write about it.

It’s pretty common advice to not write from an open wound, and I think that’s mostly good advice—maybe not “don’t write from the open wound” but certainly don’t publish from the open wound, because you’re going to be feeling things during that open wound that you’re not going to feel the same way in six months, and publication is forever.

In terms of how it feels to write from that open wound, it’s really not that different. Either way, I have to access the way I felt about something when it happens, I have to recall what I was thinking and what the other person was doing with their hands.

I think something that personal essayists tend to do is get really precious with the insights that they want you, the reader, to take away, and hammer them home in this self-serious way that I don’t think works most of the time. You want to get there in a more organic way. I don’t think you want the diary approach or the therapy approach, both of which are death for personal writing.