If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

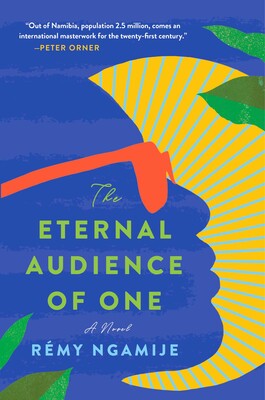

Rémy Ngamije’s novel The Eternal Audience of One is a coming-of-age story about identity, family, race, and migration set mainly in post-apartheid Cape Town.

Séraphin Turihamwe doesn’t feel at home anywhere. His family fled the Rwandan genocide for Kenya, before settling down in Namibia. He’s hoping that his move to South Africa for university will let him find a new sense of self, and of course, lose his virginity.

Ngamije weaves Séraphin’s story with those of his classmates in Cape Town, his family in Windhoek, and his ever-changing array of love interests, creating a tapestry of voices who are all searching for a sense of belonging and meaning. Relying heavily on sarcasm and the emotionally cathartic experience of curating and sharing playlists, Séraphin tries and often fails to form connections—romantic or otherwise—in the places he lives, but is not sure he can call home. As Ngamije tells me about his characters, they might be more comfortable in the search for home than in any particular destination they find themselves in.

The Eternal Audience of One shares a patchwork of stories—ranging from Rwanda to Paris, from millennials to their parents—filling out the world of Séraphin, the nerdy, cool, playlist-making student in search of his place in society.

Frances Yackel: Can you tell me about the genesis of your book?

Rémy Ngamije: The start of the story—the hardest question first, huh? Fair enough.

It is hard to pick out one particular “Let there be light” moment. Rather, in my case, different but connected events helped to usher the narrative from dream to draft—so my genesis story is more like ambient lighting slowly growing brighter than an almighty thunderclap followed by, boom, creation.

I really wanted to write a story about immigrant life in Africa. Most of the books I read had African immigrants moving to the West.

When I was at university in Cape Town, I really wanted to write a story about immigrant life in Africa—specifically, Rwandans in diaspora. This was quite intimidating because most of the books I read had African immigrants moving to the West. Not being afforded that opportunity, I did not think my story was relevant. By 2009 the idea of Séraphin had come to me and taken root. I could hear his cocky voice and I understood his worldview. But that was all—a voice, no narrative.

Around 2011, I wanted to write a story about navigating the complex and confusing world that was student life in South Africa. It proved to be quite hard, though, to write about something I was personally living through; I did not have the necessary distance from the instances of life that were busy unfolding—it was all experience but no reflection.

Then, in 2013-ish, I really wanted to have a multilayered narrative about immigrant struggles, hustles, university life, love, and attraction—you know, all of these grand themes that look wonderful when you list or cite them. I did not have the skill to put them on paper so I just let them float around in my head, in my notes, journals, and voice notes.

Finally, in July 2016, I became frustrated enough with myself to write something. I collected all of my notes, my vague plots, and character sketches with the intention of choosing one to write about at length. Looking at everything, I realized all of them existed in the same universe—all I had to do was arrange the timeline. And that, really, is how it all came together.

But the source, that chaos before time, I really cannot remember the exact moment when I knew this was the story.

FY: As a Rwandan-born man, raised in Namibia, going to school in South Africa where he is frequently racially profiled, Séraphin left me deeply moved by his constant search for a sense of belonging and acceptance:

“Home, to him is a constant source of stress, a place of conformity, foreign family roots trying to burrow into arid Namibian soil which failed to nourish him.”

In fact, all the characters in the novel seem to be on the search for the same thing, as the novel takes us all around the world with auxiliary characters. Can you tell me more about this?

RN: Migration of any kind, really, is moving from one clearly defined source of home to search for another. That search, sometimes, becomes “a home” because everything else is never perfect, never enough to stop the search in the first place. There is this strange phenomenon when the search provides a sense of home because, at least, the search has a certain regularity and certainty attached to it (moving around, adjusting and acclimatizing, realizing that the current milieu is not enough, looking for better—it sound strange, but that search for better, for more is sometimes more constant than anything else) as long as the “new home” has not been found. Séraphin, I think, is the clearest example of the person “in search of”—but every other character is also trying to find their own places in the world, places in which they can be themselves, where they are permitted to live in the full dignity of their respective essences.

FY: What is the significance for you of writing a contemporary novel about young middle-class African millennials, trying to find themselves and their place in society?

RN: I think, as a storyteller, I needed a group of people who were not adequately explored in literature. I know, for example, that Western millennials are the focus of quite a few long-form essays and social commentary. They are, in accordance with the existing structures of representation and recognition, afforded generous spaces in art and literature.

I found African millennials to be a rich source of storytelling. They also allowed a freedom of exploration because they are not regular literary occurrences.

For me, as characters in a story, I found African millennials to be a rich source of storytelling because I could understand their motivations, aspirations, and frustrations—they provided me with some sense of certainty in that regard. But they also allowed me a freedom of exploration because they are not regular literary occurrences. As a strange alloy of old world and new school—with not enough of either characteristic to claim an authoritative place in their respective worlds—they were interesting people to write about. As a work of African literature, I am excited to have The Eternal Audience of One adding to the understanding of the breadth and depth of continental writing and, hopefully, being a compass guide for other contemporary works.

FY: I was fascinated by Séraphin’s interest in and talent for creating playlists. I love the way he sees them as a way of telling a story, or rather, of bringing the listener on a journey. Does music impact or influence the way you create stories?

RN: Songs have moments in them that I wish I could capture through writing—like the opening notes of Sadé’s “King of Sorrow” or the Buena Vista Social Club’s “Chan Chan”. The feeling of those sounds, the emotions they stir immediately upon hearing them, I really wish I could put that into words. I fail, but I try. When I write—even something as seemingly simple as an email—I do not listen to music because it is quite distracting. I need to focus on the work and words in front of me. But before writing something like a short story or a chapter, I spend quite a lot of time listening to music and trying to place myself in the right emotional state of mind to write the narrative I am working on. And once a piece of writing is done, I compile a playlist for it just to see if I captured the general mood of the work. If I can find a rudimentary soundtrack for a story, I am usually on to something.

FY: Do you make playlists yourself, and if so, does your philosophy on playlists mirror that of Séraphin’s?

RN: In many ways, yes. I make playlists for everything. Gym, cooking, cleaning and laundry days, braais (cookouts), games nights, pensive walks, sunny days when university nostalgia is high, cold days for dreaming—I have so many playlists.

Séraphin’s philosophy is that playlists must take you into a mood and take you out of it. I agree. He also believes that a playlist cannot just have “bangers” on it—those are facts, no cap. It is not curating, for example, if all one does is go for what is known or popular: there has to be a sense of exploration in a playlist and the chance for a listener to discover a new song, and there has to be nuance in it, in the sense that a playlist needs to be thought about. What is it trying to achieve? Who is it for? When is it for? That kind of thing. I used to have a rule that any one song could not appear on more than three playlists—just so that I could curate as many songs as possible—but I have bent that rule on occasion. Then, Séraphin also considers it a cardinal rule never to have more than two songs by the same artist on the same playlist. I respect that. Makes making a playlist more challenging. The only exception, really, is when compiling an entire playlist curating an artist’s work—the challenge lies in ordering the songs in an interesting listening order. Trust me on this: there is a way of arranging Britney Spears’ songs that will narrate the sad situation in which she finds herself with regard to her conservatorship, and there are so many ways of arranging Alanis Morissette’s catalogue to tell different stories. I consider playlist-making to be an artistic process. If you consider it as an act of curation, it really changes the way one thinks about music—and any art for that matter.

FY: How has your experience of moving to Namibia informed your career as a writer? Could you talk a little about founding Namibia’s first literary magazine Doek! Literary Magazine?

RN: If there is anything that living in Namibia has bequeathed me, it is a sense of humor. This country, sometimes, feels like a joke without a punchline. There are moments when I cannot help but break the fourth wall and look off to the side, at the camera, and Morse Code blink at the audience, “Save me.”

As a citizen, I hope for better; as a writer, I am thankful for the canvas.

For the longest time, being a writer in Namibia was quite discouraging, because writers from here never appeared in literary magazines or prize shortlists.

For the longest time, being a writer here was quite discouraging because writers from this part of the world never appeared in literary magazines, anthologies, or prize shortlists. Namibian writers, quite simply, do not share the same level of representation that Nigerians, South Africans, Zimbabweans, and Kenyans enjoy in the literary world. Doek! Literary Magazine was an answer to that problem: what and where are Namibian writers, poets, and visual artists, and how does one share their work with the world?

Since 2019 the magazine has been injecting local writing into the national and continental consciousness. It has been hard, exhausting, and rewarding work—now there is a national and international curiosity about the stories that come from this place, and the writers, poets, and visual artists who tell these stories.

FY: What is the literary scene in Namibia like? Has the literary scene in Namibia changed since you’ve moved there? Where do you see the future of the literary scene heading?

RN: The prevalent fact of artistic life in Namibia is that it is harsh, more so than in many other places because the arts—especially the literary arts—are not supported well enough for any one practitioner to make it their sole activity of enterprise. Of course, this is true anywhere—but in Namibia this fact is law.

But even for such a challenging and limited arts scene, very little stays still here. Deserts, for all of their stillness and bleakness, can be quite active sites of life. Thus, there are more participants in the literary scene now than there were when I was in high school, for example. The hard part lies in keeping various artistic circles stable and rewarding to the artists.

There are reasons for optimism, though. Doek, the arts organization that publishes Doek!, launched the Bank Windhoek Doek Literary Awards, the first such awards recognizing literary artists in Namibia. There are also creative writing workshops that seek to nurture promising Namibian writers and poets. In time, with more funding and institutional support, perhaps we can produce anthologies and host festivals. Perhaps these are dreams, but if The Eternal Audience of One can go from Windhoek to the world, then hope remains.