Budgets are tight at NASA, especially for its science programs. NASA’s Science Mission Directorate sought an increase of nearly half a billion dollars in its fiscal year 2024 budget proposal last year, but when Congress passed a final spending bill March 8, it instead got a cut of the same magnitude.

Its 2025 budget proposal, released three days later, sought a modest increase, to about $7.57 billion. But last year’s budget request had projected spending nearly $8.43 billion on science in 2025.

“It’s about a billion dollars less,” said Nicola Fox, NASA associate administrator for science, at a March 25 meeting of the NASA Advisory Council (NAC) science committee. “It’s very challenging.”

NASA in general, and science in particular, has always have ambitions that exceeded available budgets. The 2025 budget proposal, though, is particularly severe, with NASA forced to recalibrate its science portfolio to fit into a budget significantly smaller than what it had expected just a year ago. That means some missions, including those prioritized by past decadal surveys, are in danger of being delayed or canceled.

MSR TBD

The biggest problem is with Mars Sample Return (MSR). A top priority of the last two planetary science decadal surveys, it is caught up in problems of its own making — cost overruns and schedule delays — exacerbated by fiscal uncertainty.

NASA is still working on its reassessment of the MSR architecture to address its cost and schedule problems. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, speaking at a March 11 briefing about the budget, said it should be ready in April.

So, when NASA released its fiscal year 2025 budget, it listed MSR’s funding as simply TBD: to be determined. Nelson and other agency leaders said NASA would provide an amended budget request after it completes its review of MSR.

“What does that mean, TBD?” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, to anxious planetary scientists filling a ballroom at the Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference just hours after the release of the 2025 budget proposal. “We’re trying to give the response team time to complete their assessment and provide their recommendation.”

That move took many by surprise. “That’s astonishing. I’ve never seen anything like that before,” said Casey Dreier, chief of space policy at The Planetary Society, in a webinar on the budget proposal by the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA).

The budget proposal offers $2.73 billion for planetary science, about the same as what NASA received for 2024. Glaze noted it keeps the Dragonfly mission to Titan and NEO Surveyor space telescope on schedule. It also restarts work on VERITAS, a Venus orbiter mission that was put on hold in 2022.

However, the entire $2.73 billion is allocated to those other programs, leaving nothing for MSR. Once NASA develops a revised approach to MSR, it plans to amend the budget, which will mean taking money from other programs. “I do not expect the top-level planetary budget to go up above $2.73 billion,” she said.

NASA also has yet to determine how much it will spend on MSR in 2024. The final spending bill directed NASA to spend at least $300 million on MSR, the amount in a Senate bill, and up to $949.3 million, the amount in a House version and the agency’s original request.

The uncertainty regarding 2024 budgets caused NASA last November to slow work on MSR as a precaution should the lower Senate spending level be enacted. That caused ripple effects that led the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the lead center for MSR, to lay off more than 500 employees, 8% of its staff, in February.

NASA is still dealing with the congressional fallout from those decisions, particularly from members of California’s delegation. “You left us in the dark, frankly,” Rep. Mike Garcia (R-Calif.) told Fox at a March 21 House space sub-committee hearing. “I really would have appreciated a heads-up that we were going to lay off close to 600 employees at JPL before that decision was made.”

Garcia noted at the hearing that he and nearly two dozen other members of Congress of California sent a letter to Nelson the day before the hearing, asking NASA to spend at least $650 million on MSR in 2024. However, that would likely require cutting other planetary programs given overall reductions in planetary science in the spending bill.

Decouple, partner and compete

The Earth science decadal survey published in 2018 recommended NASA pursue a series of missions for what it called “designated observables,” which range from aerosols in the atmosphere to geology. NASA responded to the decadal with its Earth System Observatory line of missions announced in 2021.

The 2025 budget proposal, though, would make major changes to Earth Systems Observatory. That is caused by budgets that have not grown as much as expected, creating what Karen St. Germain, director of NASA’s Earth science division, called a “snowplow effect” as programs were delayed.

“These unfilled budget requests stacked up to create this growing gap that, if you ran it out through the de-cade, is north of $1 billion,” she told the National Academies’ Committee on Earth Science and Applications from Space March 20. “We had to adjust our approach to building out some of our decadal missions.”

The biggest impact is the Atmospheric Observing System (AOS), a pair of missions called AOS-Sky and AOS-Storm that NASA previously estimated would cost up to $2 billion to develop. AOS-Storm will be replaced by a partnership with Japan’s Precipitation Measurement Mission, while AOS-Sky will shift from one large mission to several smaller ones, at least one of which NASA will open to competition rather than directing its development.

It is part of a broader strategy for the Earth System Observatory called “decouple, partner and compete” that makes greater use of international partnerships and competition as well as smaller missions. “Instead of having large, coupled architecture, missions fly when they’re ready,” St. Germain said. “We’re decoupling the risks.”

The budget documents illustrate those cost savings. In 2024, NASA pro-jected spending nearly $1.3 billion on AOS between 2024 and 2028, including about $250 million in 2025. The new budget proposal projects spending about $660 million on the replacements for AOS from 2025 to 2029, with less than $70 million in 2025.

Another Earth System Observatory mission, Surface Biology and Geology, will be split into two smaller missions launching as much as four years apart. NASA is also dropping plans for a third mission, Surface Deformation and Change, relying instead on the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) mission, a joint U.S.-Indian proj-ect scheduled to launch later this year.

“Going into this budget cycle for fiscal year ’25, we knew that we were going to have to reduce some content,” said St. Germain, which led to Earth System Observatory changes. “We knew we couldn’t just keep sliding it out to the right.”

The budget proposal “is less ambitious than in years past, but we think it’s a reasonable request,” she added.

Dynamic uncertainty

Last year’s budget request proposed a three-year delay in the top flagship mission recommended by the latest heliophysics decadal survey, the Geospace Dynamics Constellation (GDC). That mission would place six spacecraft into low Earth orbit to study the inter-action between the upper atmosphere and the Earth’s magnetosphere.

The 2025 budget proposal, however, would cancel GDC outright, which Joseph Westlake, director of NASA’s heliophysics division, blamed on con-strained budgets projected through the end of the decade. “We were never able to get a large enough portion of funding to get it moving,” he told the National Academies’ Committee on Solar and Space Physics March 20.

“It was an awful thing to keep people paused, so the decision was to cancel it,” Fox, who was previously heliophysics division director, told the NAC science committee.

The proposed cancellation of GDC could affect another mission, called Dynamical Neutral Atmosphere-Iono-sphere Coupling (DYNAMIC), that NASA solicited proposals for last year. GDC and DYNAMIC were supposed to work together, and the proposed termination of GDC makes it unclear whether or how DYNAMIC could proceed.

“I see that coupling as both a blessing and a curse,” Westlake said of the ties between the two missions, “and it’s going to be a challenging, tricky situation for us to navigate.”

GDC does have a potential lifeline from Congress. The report accompanying the 2024 spending bill directed NASA to conduct a study in the next 180 days about how it could fly GDC by the end of the decade, a sign that the mission has support among at least some key members of Congress.

Westlake said NASA was just starting work on that study, and had no further direction about the study beyond the language in the report. “There’s wide room for interpretation,” he said.

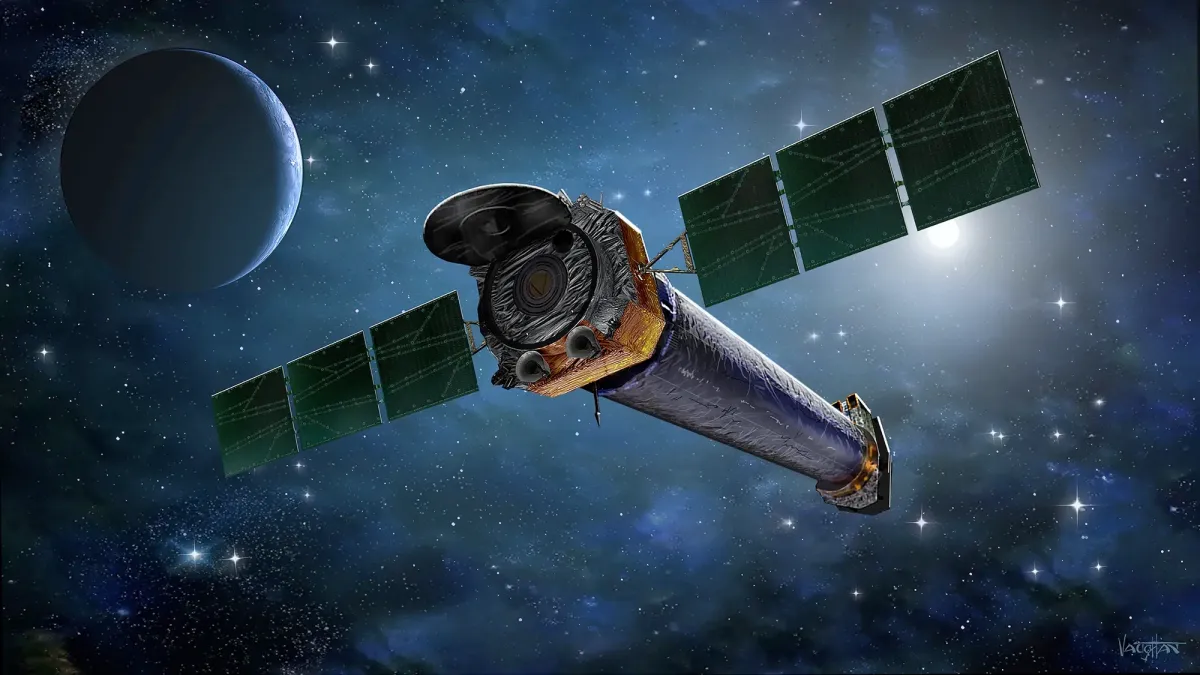

Chandra concerns

Perhaps the biggest outcry about the budget proposal, though, came from one of the smallest cuts on an absolute dollar basis. NASA proposed reducing the budget of the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, an X-ray telescope launched in 1999 as one of the original “Great Observatories,” from $68.3 million in 2023 to the proposed $41.1 million. The Hubble Space Telescope, the other remaining Great Observatory, would get a smaller cut.

While a reduction of less than $30 million, it represented a 40% cut for Chandra, one that astronomers argued put its future into jeopardy. NASA’s own budget documents stated that the reduction “will start orderly mission drawdown to minimal operations.”

In an open letter a week after the release of the budget, Patrick Slane, director of the Chandra X-Ray Center, said the budget was too low to do science, adding that “the minimal operations referred to in the budget document would actually be decom-missioning activities.”

NASA officials defended the proposal at a March 20 meeting of its Astrophysics Advisory Committee, or APAC. “We cannot, with the budget that we have right now in ’25 or the outyears, fund these missions at the level they’ve been funded at in the past,” said Mark Clampin, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, of Chandra and Hubble.

NASA is preparing what officials have called a “mini senior review” to examine how operations of Chandra and Hubble could fit into those reduced budgets. But astronomers have objected to that terminology since the process — formally known as the Operations Paradigm Change Review — lacks the input and review from the scientific community NASA traditionally uses in its senior reviews of extended missions.

Eric Smith, associate director for research and analysis in NASA’s astro-physics division, told APAC that NASA took this approach because it wants the review complete by the end of May as it works on next year’s budget proposal. “We just don’t have time to engage in a big, widespread poll of the science community.”

“The budgets mandate that these missions work differently than they have in the past. There will be science impacts,” he acknowledged.

Astronomers, though, remain worried that the proposed budget for Chandra will mark the end of the telescope. The grassroots SaveChandra.org effort has started to lobby Congress to reject the proposed cuts to that telescope, warning that the proposed reduction could result in the “prema-ture loss” of the telescope, and with it, “a death spiral for X-ray astronomy in the United States.”

Next steps

The fiscal year 2025 budget proposal has gotten little attention on Capitol Hill so far, in part because Congress was still busy for two weeks completing the rest of the fiscal year 2024 appropriations.

An exception is Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), who serves on the Sen-ate appropriations subcommittee that funds NASA. “If you look at the budget request, it does tilt more towards exploration than towards essential science,” he said in a March 19 Maryland Space Business Roundtable speech. The budget proposal keeps exploration programs flat in 2025 after a modest increase in 2024.

He added that some missions being led by the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland “do not have adequate funding” in the request. “I can assure you that, as we review this budget, we are going to work hard to make sure that Maryland’s priorities, which are national priorities when it comes to funding science, are included.”

Van Hollen and fellow appropriators may not have much room to maneuver, though. Jean Toal Eisen, vice president of corporate strategy at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy and a former Senate appropriations staffer, noted at the AIA webinar the Congress used some budget cap space in fiscal year 2025 in the 2024 spending bills to lessen the effect of the cuts on some programs. “We’re looking at some re-ally ugly numbers in FY24, especially for science agencies like NASA, but it could be worse in FY25.”

NASA hopes to get some breathing space in 2026, when the budget caps from the Fiscal Responsibility Act expire. “We’re not going to get out of this hole until you finish both fiscal years, ’24 and ’25,” Nelson said.

Dreier, though, noted NASA’s bud-get proposal projected growth in the science budget at only 2% annually, less than the current rate of inflation, through the end of the decade, creating “a slow bleed of resources.”

“My worry,” he said, “is that none of the major flagship missions are going to be possible under this budget scenario.”

This article first appeared in the April 2024 issue of SpaceNews magazine.

Related

Read the original article here