Accept Irrelevance! You’re Being Replaced!

The Replacement by Alexandra Wuest

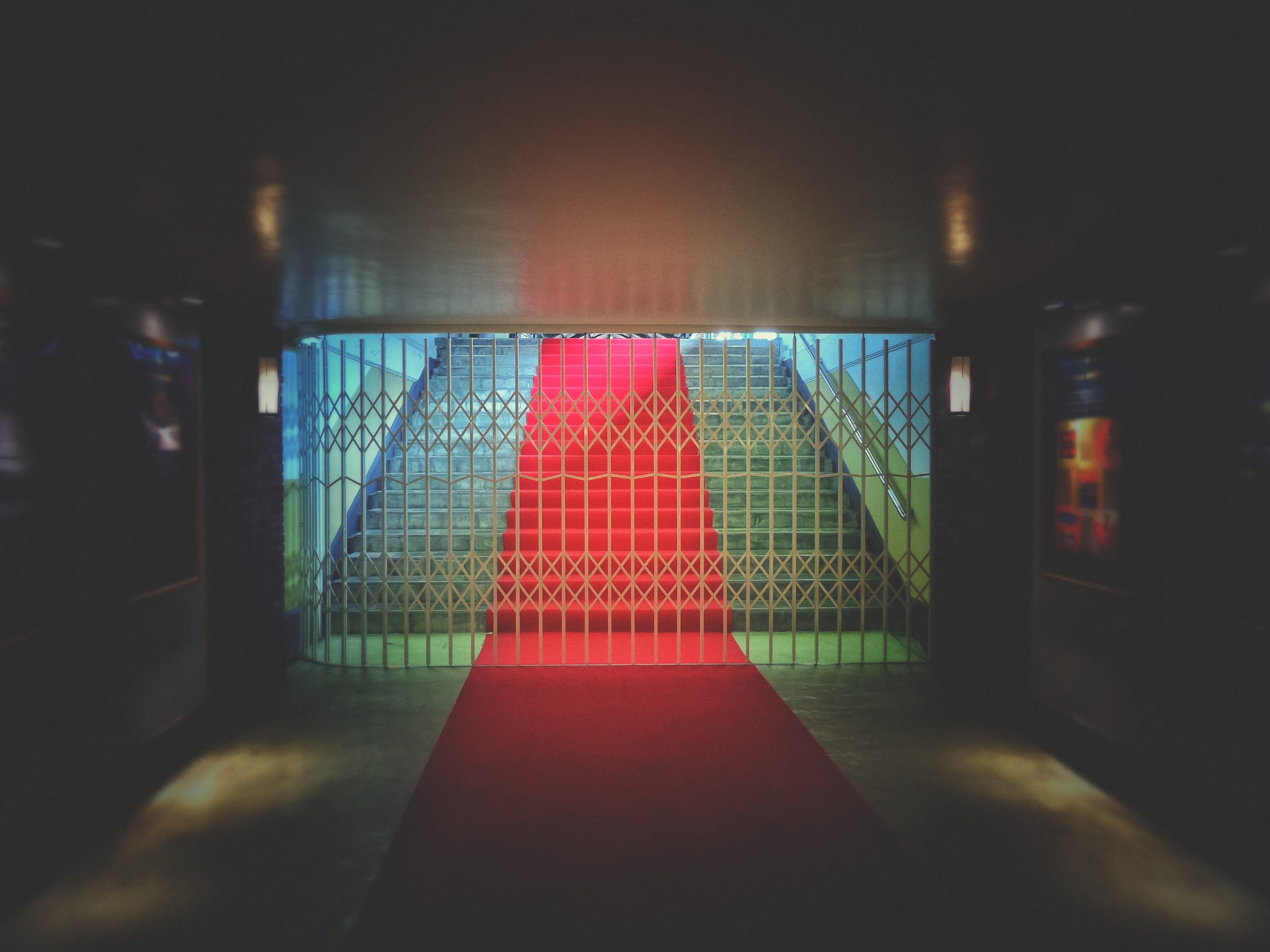

The news comes in the form of an email. YOU’RE BEING REPLACED, the message says, and I glance around the office. The typists are typing, the copy machine is copying, and the shredder is shredding. The room looks like the type of workplace you’d see in a movie set in an office, not a Post-It note out of place: cubicles, computers; shades of grey and blue; the soft sounds of machinery filling the background. Everyone is acting the way they always act.

I walk into my boss’s office. She appears to be in the middle of doing something very important on her computer while riding a stationary bike. In the corner of her office, there is a trash can overflowing with hundreds of half-eaten chopped salads, and her desk is littered with lipstick-stained cups and bottles of every beverage imaginable. When she doesn’t notice me, I knock on the doorframe, and she stops pedaling and looks up.

Am I being replaced? I ask.

Oh good, she says. They told you. Things have been so busy around here I was worried I’d have to do it myself.

She steps off of the bike, rifles through a desk drawer, and pulls out an ornately decorated cupcake. She hands me the treat with a smile.

ACCEPT IRRELEVANCE is written in pale pink frosting across the top of the cupcake. I take a bite, and the cupcake tastes like a mixture of refined sugar and unrefined pity.

Why? I ask, my mouth full of dry cake crumbs.

We just feel you’re not the right fit, my boss says. It’s nothing personal, but we’ve found someone who’s a better match for the position. She hands me an empty cardboard box. Here, you can use this to pack up your belongings.

Back at home there is a problem with my key. It no longer fits inside the keyhole on the front door. No matter how many times I try, I can’t get the front door of my apartment to unlock. The key is suddenly a mismatch. I put my box of personal items from the office down on the ground and look around for the spare my boyfriend and I hid when we first moved in. It isn’t in its usual place under the doormat, so I bang on the door with a fist.

Boyfriend! I yell, and inside I can hear the sound of footsteps. A few seconds pass, and the front door finally creaks open to reveal my boyfriend standing in the doorway with an apron tied around his waist.

I hold up my key and begin to explain that it no longer fits in the keyhole, but my boyfriend interrupts me before I can finish.

I have to stir the sauce! he says. I don’t know what sauce he is referring to. He doesn’t usually refer to sauces at all. He rushes down the hallway toward the kitchen.

I pick up the box and follow him inside where I find him at the stove stirring an enormous pot of marinara sauce. I’ve never seen my boyfriend cook before, but tonight the kitchen table is piled high with crystal platters overflowing with food: piles of shellfish, a rack of lamb, freshly baked bread still steaming from the oven. I pick up a caviar-dusted deviled egg and watch my boyfriend strain spaghetti at the kitchen sink.

What’s all of this for? I ask.

To celebrate! he says.

Celebrate what? I ask. The fact I got fired today?

My boyfriend makes a face like he’s forgotten to take a soufflé out of the oven, which it turns out he has. He turns away to rescue dessert, and we both hold our breath as he pulls the chocolate soufflé out of the oven. He closes the oven door and wipes his hands on his apron before turning back to look at me.

About that, he says, and his eyes dart around the room. I follow his gaze and find three overstuffed suitcases waiting in the corner by the trash can.

What are the suitcases for? I ask.

Your stuff, he says. Your replacement will be over shortly. She’s finishing up some things at the office. That’s actually why we’re celebrating. She got promoted already!

She’s replacing me here too? I ask. I thought that was just a work thing.

What’s the difference between life and work these days? he says. He returns to the stove to stir the giant vat of sauce. A second later, he raises a single finger in the air as though trying to determine the direction of the wind. Hold that thought, he says. I have to send some work emails. He puts the wooden spoon down and bends over a laptop perched nearby on the kitchen counter. When he is finished typing, he closes the laptop and looks back up at me. Sorry, where were we?

Where am I supposed to go? I ask.

Have you checked your email? he says.

I wait for the train to arrive and read through my inbox. Apparently, the email had gone to my spam folder by mistake. The subject line says, NEXT INSTRUCTIONS, but when I click on the email the body of the text only reads: TBD. I don’t know who to contact about the oversight. I put the phone back into my pocket and watch the train pull into the station.

Almost all of the seats on the train are already full. As I walk down the aisle in search of an empty seat, I can’t help but notice all the passengers have something in common. They all look a lot like me. Some more wrinkled, some more taut; some with beauty marks, others with boils. I walk through train car after train car trying to locate an empty seat.

When I finally find one, I sit down and pay a conductor in a blue hat for a one-way ticket. Sitting to my left is an elderly woman. She too looks a lot like me—only about one hundred years my senior. She has a newspaper spread open on her lap.

Where are you headed? she asks.

To my parents, I say.

Oh that’s nice, she says, and the train makes noises to announce it is departing the station. Outside the window the landscape starts to blur.

Where are you going? I ask.

To my parents, she says and laughs hysterically. I join her in laughing, but I don’t know if we are laughing because her parents are likely very old or if we are laughing because her parents are likely very dead. I make a pillow out of my hands against the window and try to fall asleep.

I wake up to a finger poking me in the ribs. I open my eyes. It is the elderly woman trying to get my attention.

Do you want any sections of the newspaper? she asks. She holds the paper a few inches from my face. I’m still half-asleep but I nod groggily. She hands me the style section, and I browse the wedding and engagement announcements until I see a familiar face.

It’s my boyfriend printed in black and white, smiling up at me. I’ve never seen the beautiful woman standing next to him before, but I know who she is immediately. She has thin upper arms and a smile that doesn’t show her gums. She has a knack for arts and crafts and a head for business. She can dish it out and she can take it. She is my replacement, and I stare at the diamond ring glittering on her finger. The picture is small, but the stone still looks impressive.

The article says my boyfriend proposed by hiring a skywriter to write WILL YOU MARRY ME in the clouds. It occurs to me that my boyfriend and I were together for a total of six years and never discussed future plans, let alone marriage or proposals written by airplanes. I scold myself for always forgetting to look up at the sky and crumple the newspaper into a ball.

Hey! the woman says, snatching the paper back from me. I haven’t read that section yet.

The conductor returns to our row.

Excuse me, ladies, he says. It appears we have a problem.

No problem here, I say. Just a misunderstanding about a newspaper.

Next to me, the woman grunts in disagreement.

I wasn’t referring to a newspaper, the conductor says. He leans in close to my seat and lowers his voice to a stage whisper. I’m sorry, but it seems your seat has been double booked.

Behind me I hear the sound of a woman clearing her throat and turn around to see my replacement standing a few feet away, a single dainty suitcase in her hand. She smiles in my direction.

You can have the seat, she says warmly. I can stand, it’s no trouble at all.

The train conductor beams at my replacement. She looks even more beautiful in person than she did in the newspaper photo. Her skin is pore-less, her posture is ballet-straight, and her breath smells like a dentist’s idea of heaven.

Now, that’s very generous of you, the train conductor says, but with a selfless attitude like that, we couldn’t possibly allow you to give up your seat.

Really, I don’t mind!

No, no, no. He shakes his head. Follow me, I think we all know a person like you belongs in first class.

He takes her by the arm and leads her towards the front of the train. Before they disappear into the next car, the conductor turns back to shoot me one last simmering stare. He wags a finger in my direction and looks as though he has something more to say to me, his face resembling a cat about to hiss, but he turns and continues toward first class with my replacement.

When they’re out of sight, the elderly woman turns to me excitedly.

That’s the lady from the newspaper! she says.

I know, I know, I say. Who announces their engagement in the newspaper anyways?

No, the woman says. Not that. Look, she’s on the front page. She puts on a pair of enormous reading glasses and hands me another section of the newspaper. Sure enough, on the front page is another photograph of my replacement. In this photo, she stands with a pair of comically oversized scissors in her hands and appears to be in the middle of a ribbon-cutting ceremony.

It says here she uses all of her vacation days to visit towns that have been destroyed by earthquakes and tornadoes and floods, and rebuilds the schools and hospitals and playgrounds all by herself, the woman says. Isn’t that something? And on top of that, she works a full-time job.

Wow, I deadpan. How selfless.

Oh, look here, the woman says, pointing to the final paragraph of the page-long article. This says she just got promoted at work—again!

I stare out the train window and watch the landscape become more familiar and stranger at the same time. Outside, the neighborhood where I grew up is coming into clear view, but all of the businesses I once knew have been replaced. I barely recognize the train station when the conductor comes over the loudspeaker to announce we have reached our destination.

When I finally arrive at my parents’ front door I don’t bother trying my old key. I don’t want to take any chances. Instead I knock on the door, which has recently been repainted a new color, and yell, Mother! Father! It’s me!

When the door opens, it isn’t my mother or father who opens it, but my replacement.

Oh, come on! I say, when I see her standing in the doorway.

She is wearing a different outfit than she was on the train and is freshly showered and blow dried. It’s possible she’s gotten a new haircut in the short time since we parted, a difficult to pull off style that she does in fact pull off. She doesn’t look like someone who spent several hours on a train and then another hour walking uphill, but then again, she was carrying considerably less luggage than I currently am.

What are you doing here? I ask.

What do you mean? she says. This is my family.

I can hear my mother’s voice shouting in the background. Honey! Who is it at the door?

I elbow my way around the replacement and find my mother on the living room sofa flipping through albums of old family photos.

Mother! I say. She looks at me as though I am an item on a menu that doesn’t meet any of her dietary restrictions, like something wrong, something to be sent back, or something to be avoided entirely in the first place.

Who are you? she says.

Don’t you recognize me? I ask. I’m your daughter.

No, she says, getting up and standing next to my replacement. This is my daughter.

I try to think of a way to prove I am who I say I am. I walk over to the photo album she is holding and point to a family portrait. I am twelve years old in the photo. See? I say.

See what? she says. That isn’t a picture of you.

I look closer at the photo and see she has a point. The child in the photo doesn’t wear the unflattering bowl cut or the orthodontia-neglected smile of my childhood; doesn’t share my adolescent habit of standing as though my hunched shoulders are an apology for the mere act of existing. Instead, the child in the photo looks like the replacement standing in front of me, only younger, and her very presence in the photo makes the rest of the family in the portrait appear a little lovelier too, both the same and not at all in my absence.

I pace around the room, trying to think of an alternative method to prove to my mother that I am her daughter.

Well, I say, if I wasn’t your daughter how would I know about the time you bought me gerbils for my tenth birthday? And how I accidentally let them escape and they got into the walls of the house and ended up having hundreds of babies? And how it took us months to find all the babies and how years later we’d sometimes hear scratching in the wall and realize we hadn’t found them all?

My mother makes a face like she is doing algebra in her head.

That sounds pretty irresponsible, she says. And unappreciative of such a thoughtful gift. I don’t think my daughter would do that. She puts an arm around my replacement.

How about the time I wrecked dad’s car a week after I got my driver’s license? I say. Or when I got so depressed in college I had to come home, and the doctor said the reason I was sad all the time was because I ate only pancakes for the whole semester? Or what about the time we all went to Bermuda on a family vacation and I locked myself in the hotel room for the entire trip because I had my period and was afraid of being eaten by sharks?

My mother shakes her head. My daughter would never do those things. She shows up to my house with flowers and gifts and bouquets of chocolate-dipped fruit. If you’re supposed to be my daughter, where are your flowers, your gifts, your bouquets of chocolate-dipped fruit?

I look at my overstuffed suitcases and the box from the office.

I didn’t bring any flowers or gifts or bouquets of chocolate-dipped fruit, I say.

Tsk, tsk, my mother says. Definitely doesn’t sound like my daughter. Plus, you have a certain brittleness about you. My daughter wouldn’t have that. She goes with the flow. She’s always trying to help others. She never asks for anything. She doesn’t have all this . . . baggage . . . that you seem to.

She picks up the box from the office and hands it to me.

I think you should take your things and go, she says.

My replacement gives me a pitying look. Here, let me help you with your suitcases, she says, but I don’t accept her assistance. These are my things and I don’t need anyone else to help me carry them.

As I walk away from the front door, I can hear my family cheering inside the house. Another promotion? my father’s voice yells. Let’s celebrate! Someone is blowing into one of those noisemakers they sell at party stores. I turn around to try to catch a glimpse of my family through a window but find that my mother has already pulled the curtains shut.

I walk for what must be several days. All the trains that pass by are fully booked, not a single empty seat available for me to purchase, and every day my luggage seems to grow heavier and heavier. Eventually, when I can barely lift the suitcases, I stop by a weigh station and the scale confirms my suspicions.

I begin to take things out of the suitcases to make them less heavy: out-of-style clothing, unread books, supplements I’ve consistently forgotten to take, dirty socks, the guitar I never learned how to play, overpriced facial serums, half-finished and long-ago abandoned knitting projects, expired tubes of mascara, a dust-covered yoga mat, pants that no longer fit, a broken umbrella I’d been meaning to replace. As I walk I scatter my belongings behind me one by one like a trail of breadcrumbs that leads to my parents’ house, to my former self—to my replacement? I’m not sure anymore. Things are getting fuzzy. As each suitcase empties, I leave the luggage behind too.

Another day passes and I’m down to only the cardboard box. All I have left now is what I took from the office. I can barely remember packing them: a dying houseplant, a bottle of hand lotion, a photo of my boyfriend and I summiting a mountain, a punch card for a coffee shop near the office that is just one punch away from a free small drip coffee, a birthday card signed by everyone in the office in which half of my colleagues misspelled my first name. The things I once put on my desk to mark it as mine, but now have no use for.

I turn a corner and realize the streets resemble something I remember from a dream. I look around and realize it’s not a dream at all—I’m almost exactly back where I first started, just a few blocks away from my office.

I hoist the box onto my hip and continue walking in the direction of the building. I don’t know what I’ll do when I get there but it feels good to have a destination.

As I get closer, I notice there is something different about the block than the last time I was here. It is lined with movie trailers. I pass by a table laid out with craft services and walk up to one of the trailers. There is a sign on the door that says CASTING. I knock on the door.

A man with a baseball cap and a headset around his neck opens it.

Can I help you? he asks.

Can you tell me what is going on? I ask, pointing to the rest of the trailers lining the street.

We’re filming a movie, he says, and looks me up and down. Actually, we’re in need of some extras. Do you have any time to kill?

I look down at my box of belongings. I won’t be needing my things anymore, so I put the box down on the ground and follow the director into the office building.

As we walk he explains the movie is set in an office, an office that happens to be my old office. When I had worked there I hadn’t realized it was a movie set.

The director tells me where to stand and I follow his directions. He hands me a stack of papers that are entries from my childhood diaries, outlining all the various ways I have disappointed myself and others throughout the years.

Here, he says. You can shred these in the background of the next scene.

Won’t the shredder be too loud? I ask the director.

Good catch! he says. You’re a natural at being an extra. He hands me another stack of papers. You can work on filing these instead.

This new stack of papers is a collection of news clippings celebrating my replacement’s myriad accomplishments. The stack is as thick as the stack of my diary entries—maybe thicker.

Should I file them alphabetically? I ask.

Doesn’t matter, the director says. You’ll barely be on-screen. He turns his hands into a frame, closes one eye, and pans his fingers around the room like a camera.

It’s funny, I begin to explain. I actually used to work in this office—

Quiet on set! the director yells, and a hush falls over the crew.

I watch as the movie’s two leads are guided by a PA to a pair of Xs taped onto the carpet.

The scene is a love scene, and I watch the main characters rehearse their flirtation by the water cooler. They make working in an office look so much more romantic than when I was doing it myself. I think of the days when I was the new girl in the office, but it feels like a story that happened to someone else. It’s possible I’m mistaking something I saw late at night on TV for a memory.

Action, the director yells, and I watch the camera make slow circles around the couple. I’m far enough away that I can’t hear what they’re saying, but I can see their faces, and I recognize the woman. She’s my replacement, and I have to hand it to her, she’s doing a better job with the role than I ever did.