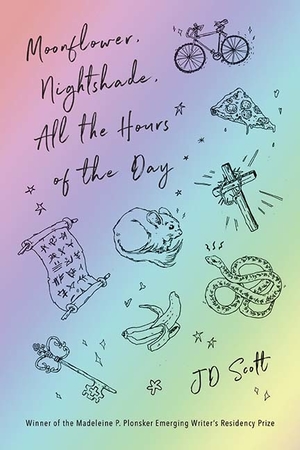

JD Scott’s debut short story collection, Moonflower, Nightshade, All the Hours of the Day, calls on myth and magic, Florida and fabulism to tell stories of queer youth seeking out love and transformation within a world in crisis (and in the case of the collection’s novella, “After the End Came the Mall, and the Mall was Everything,” a world post-crisis).

There is a wry, constant humor and so much poetry that these stories sing as they wind through baroque lives and landscapes: a chinchilla is an amulet that keeps a couple together; a perfume maker poisons his boyfriend, slowly, carefully, beautifully; angels observe a generation of men abandoned by their families, dying alone of AIDS. The world is for the young, Scott tells us, but it is not always a good, kind, or fair world. And yet, somehow, there is laughter and hope.

The collection weaves between YA, fantasy, science, and literary fiction, and this fluency creates a floating, dream-like quality to the stories, and the spaces between them. Scott’s dreams are beautiful and familiar, even when unpleasant, and they will linger long after you’ve left them.

Nicole Treska: You and I have talked about the poetic quality and potential of writing across literary genres, why is that so interesting to you?

JD Scott: There are these spaces that light my brain on fire, in a way. I grew up reading Diana Wynne Jones and Brian Jacques, stories that were more adventure-focused, or fantasy-oriented, as well as fairy tales. That was my first learning experience with writing. That becomes part of you. My approach to these things isn’t necessarily the approach of what someone who holistically reads fantasy or sci-fi would be, because I think if you’re reading fantasy and sci-fi, you’re looking for this pleasure, right? You’re looking for pleasure in these recognizable genre tropes, but I find a certain amount of displeasure in the fantastic, and that can become quite subversive in a way.

NT: These are coming of age stories, with characters falling in love, becoming disillusioned, searching for meaning in the world, with their “still fat faces,” as you described them. What draws you to these still fat-faced parts of our lives?

I’d become enamored with this idea of the ‘second adolescence,’ which is a queer concept that you might not have always been living your truth.

JS: We all have these obsessions we pursue in our writing. It was something on my mind, the idea of the youth, or the teenager. There’s this space of “anythingness,” of a certain age group that I was excited by. And I think as I got older, especially in my late twenties or early thirties, I’d become enamored with this idea of the “second adolescence,” which is a queer concept that you might not have always been living your truth, because you had to live someone else’s truth, when you were going through your first adolescence. So, you hit this second adolescence, living your truth for the first time. And that’s not necessarily my truth, but it’s something I became interested in. The performance of youth. And this idea of teenagers, this space that has these infinite futures, and space for transformation. I talked about genre tropes, and this idea of displeasure, but there has to be some balance to that displeasure. And maybe the idea of characters or even space or setting being able to be transformed balanced the displeasure. Maybe it’s a little bit cheesy, but maybe I buy into this idea of hope or tenderness. At least in as a book, at least in these stories.

NT: I had a question about “Their Sons Return Home to Die,” a story about gay men coming home to die of AIDS, to families who reject them, even then. It breaks the first-person singular narrative and goes takes a high, parable-like first-person plural, a “we,” that breaks your heart. I was wondering what about that more fabulist, fable-ish mode allowed you to capture that magnitude of loss?

JS: Everyone’s going to have a different entrance point. When I wrote that story, I was living in Alabama. I had returned to the South, after almost a decade in New York. And I had read this article about Ruth Coker Burks. This article called her the “Cemetery Angel,” because she took care of hundreds of gay men who were dying in and around Hot Springs, Arkansas. I believe she had inherited a family cemetery plot. So she had this plot of land, and she buried these dead gay men with her own two hands because, presumably, families had rejected them, and they had no one else to bury them.

Of course, New York certainly had its own relationship with the AIDS crisis. When you’re young enough to only barely remember ACT UP, like I am, you have to seek out these stories because they’re not always being passed on to you. The thing about AIDS and also the thing about gayness is most gay people are born from heterosexual couples. You have no one to teach you your lineage. And a lot of our teachers died in the AIDS crisis. I grew up in what felt like a generational disconnect. I returned to the South, which meant seeking out queer community, and by doing that I inherited this narrative of how Alabama deals with queerness.

When I was in Tuscaloosa, it was one of the first annual Pride events they had. And I remember this one woman, she was old, and she could barely stand and she got up at this gathering. It wasn’t a big, flashy Pride parade, it was like what a small Southern town might have as its first pride. And this woman was bitter. And she was mournful, and she’d got the mic and said, “We are the ones who had to watch our men return home to die.” That was the seed of that story. There was anger and a righteousness in her voice. Her voice blended with my own, and it became that “we” voice. It’s interesting because that first-person plural voice is where the angels are talking. The story is told by the angels. But of course, the angels are representative of these queer men who left to go to the cities, who left to go to New York, and San Francisco, and the new homes they created, where they could love each other and find acceptance. But unfortunately, when the AIDS crisis emerged, some people decided to leave those sort-of-heavens, to return for their families of blood, and families of origin, and places of origin to die.

That’s the fraught space where that story emerged. I’m also continuously dealing with this idea of the parable, or the Judeo-Christian stories that I grew up with, alongside Joseph Campbell and The Hero’s Journey. Those are the Bible stories I grew up with, and internalized, and I found a place for them in my work. But that’s also the transgression, to pit the biblical story and homoeroticize the angels, who are objectively queer and beautiful. And of course Tony Kushner, too. How could I not think of him after connecting the AIDS crisis to angels, and Angels in America?

NT: Do you think fabulist world-building comes more naturally to a Southern writer, who historically observe the bizarre without flinching, too much. Why do you think that Florida is capturing this moment of literary attention?

JS: With the Southern Gothic, there’s always been a sense of the uncanny, the grotesque, the derelict, the violent, the impoverished, the criminal, the alienated, the nightmarish, and the absurdist and fantastic. That’s Faulkner, that’s O’Connor. There’s something happening in Florida… what I call the Subtropic Gothic. If you look at what Joy Williams has done. There’s Kelly Link. Alissa Nutting, Jeff VanderMeer—all these people who have a connection to Florida doing very weird work. I’ve heard the term “The Florida Renaissance,” I don’t know if there’s a whole truth to that… but Florida certainly possesses a sub-genre of the Southern Gothic.

We’ve honored this type of literary novel about upper-middle-class white people. So, maybe we’re looking for other types of stories.

If we interrogate what has been normative, we’ve centered these metropolitan novels, and now we are moving into the province, to see what’s happening in other places. We’ve honored this type of literary novel about upper-middle-class white people: heterosexual, and maybe they’re getting a divorce. So, maybe we’re looking for other types of stories.

I think the most fascinating book that took off, recently, is Kristen Arnett’s Mostly Dead Things, from Tin House. She is near me, in Orlando. It deals with taxidermy, and that specific brand of Florida strangeness, and queerness…it’s a Southern Gothic novel in a way. And it’s wonderful, and because Kristen’s book was so well-received, I think it shows there is some lingering interest in Florida as a place.

NT: Yes. It’s a fascination that’s bigger than just literature.

JS: Right. That’s the whole Florida Man thing. I could easily explain that. I mean, I don’t know if that steals the magic. Florida is unique in that it has these unprecedented public record laws. When I was a teenager, 15 or 20 years ago, we used to go on the Hillsborough County arrest inquiry website, and tried to look up people or adults we knew, to see if they had been arrested. With open access, you can find all these records. So, “the news of weird” in Florida can be uncovered a lot quicker. But that’s also, I mean, but I don’t want to fully put that reasoning forward as to why Florida’s strangeness is so ubiquitous.

NT: A little bit of a Florida defense mechanism.

JS: I definitely have a Florida defense mechanism. And I don’t want to confirm the bias. Florida is weird, but I think the weirdness of Florida doesn’t always align with the idea of what non-Floridians think is weird about Florida. It’s not necessarily something you can put into words, but you see or experience something and it has a “Floridaness” to it. Like the red tide, and that’s a real phenomenon that I include in one of my stories, and is one that I experienced as a child.

I didn’t leave Florida for the first time until I was seventeen. I think that’s something else about Florida. It’s such a long state. It’s not like New England, where you can quickly move between different areas and regions. We are sequestered and isolated.

For a long time, my parents went to the same motel every summer. That was our one vacation, and we went to the same beach. It was like 90 minutes from where we lived. But I have this one memory of a year we decided to go in the winter, and it was red tide season. So not only was it unseasonably cold, but the red tide had killed all the gulf life. So it was cold and you’re walking on the beach and there were octopuses and…all these fish and aquatic life I had never seen before because they live so far in that deepness, in the depths of the ocean. I remember how wrong it felt seeing them on the shore. It’s a red tide. It’s science, right? Science explains why red tide happens. For me, those are the types of moments that become magically charged, when they’re a wrongness to it. These fish shouldn’t be on the shore, and they’re dead, and they’re perverse. They’re on display for anyone to walk by, or touch, or poke them with a stick. But there are other Floridas. When people are talking about Florida Man, they’re like, “Oh, someone got drunk and threw a baby alligator through Taco Bell drive-thru window.” And that becomes the focus and barometer of Florida’s weirdness.

NT: I know you love to play a crane game app on your phone. I’ve watched and wondered. Tell me about this. Why was it a JD Scott obsession for a while?

JS: I feel like it ignites the same place in your brain that addiction does, the reward centers. So, even though you’re on your phone, you’re actually playing a real crane game, sometimes called a UFO catcher game or claw-machine game, over webcam—you’re controlling a real one in Japan. And if you win the actual prize, they ship it to you from Japan, much to the chagrin of my USPS person. I think she retired because I was winning so many stuffed animals, but I was always at work, and never here to sign for my international stuffed animal packages. Once, I was at the post office picking up a package I missed, and the worker with like, wow, this big box is so light. It’s almost like it’s full of stuffed animals or something. And I laughed really nervously.

NT: Like, I’ll just take that package—goodbye.

JS: I mean the stuffed animals, I think they’re cute and love having them on display, but I stopped because there is no room for them in my apartment anymore. I have twenty of them. People are going to think I’m a serial killer.

NT: How much money does one have to spend on claw game?

JS: You get daily free tickets usually. That’s the exercise in self-control. There’s some pleasure there too, right? Getting one free ticket, and playing only once a day. There’s something monk-like about it. I have a lot of plants at home, and I have stuffed animals too. They do the same thing to my space, making it feel inhabited and sacred.