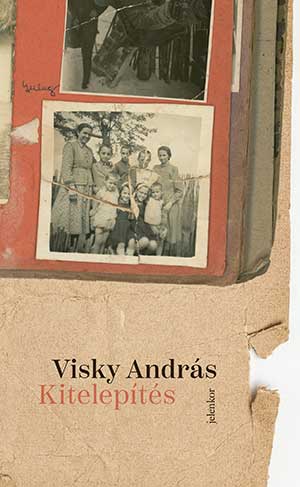

András Visky is a Hungarian author living in Romania with a body of work that spans most literary genres, from poetry to drama and fiction to criticism. His first novel, Kitelepítés [Deportation] (Jelenkor, 2022), has taken the Hungarian literary scene by storm and is already in its fifth printing. The book is rooted in Visky’s personal experience of being deported with his mother and six older siblings to a remote gulag in 1950s Romania, while their father faced an uncertain future as a political prisoner elsewhere. Despite these cruel circumstances, Visky’s story brims with dignity, love, and humor and has a universal potential to touch readers. The following is an excerpt.

506

506

forced abode comes with forced labor, only they had omitted to inform us of this, nor is there any mention at all of it in the deportation order, which simply does not provide particulars about, does not raise the issue of, does not give a name to, does not go into what the punishment will consist of, leaving no doubt only as to the fact that it concerns manifest criminality and the legal use of force

507

but then this is, after all, understandable, the Party being tied up with the creation of a new heaven and a new earth, having embarked on a large-scale, truly cosmic project, there is no time for formalities. God, for example, had promptly failed to make the grade and had been officially thrown out of the Universe, there’d been a sudden increase in the number of black marks in the class register, more and more unexplained absences. Where is God, the people asked, raising their eyes to the heavens and they had every right to do so. Not here, that’s for sure, they concluded, pointing around at the camp, and when He was called up to the front of the class, which He was every day, He’d just stand there at the board, lost-looking and silent, crumbling the chalk like He’d wet his pants and been found out. He could no longer be tolerated, that was clear, a Party order was issued stating there was no God, and He, too, was officially notified, You don’t exist. Keep your head down if you know what’s good for you, all right God-bod, it’s over

508

work sets you free, forced labor most definitely, no doubt about that, what does it free us from? well, from ourselves, that’s what they thought it up for, that’s what we’re in need of. The Party may, quite rightly be thinking that, while the people it is dealing with may be ideologically misled, they are, in their own way, intelligent, they realize the position they are in and won’t quibble at being forced to work, they will, without putting up any particular resistance, march out in neat columns on a daily basis to build a new heaven and a new earth

509

perhaps we’ll realize that organized work is for our own good, that the Party, for its part, is generously attempting to reeducate us, is generously placing its hopes in us, including Mr. Goma the writer, General Praporgescu Commander of the Royal Lifeguards, oh, and let’s not forget Marino the liberal arts scholar, and, yes, the two pale widows, Mrs. Lilica Codreanu the Iron Guardsman’s wife and Mrs. Maria Antonescu, wife of the fascist Marshal. If anyone should happen to resist or attempt to escape, he or she will, for their own good, be shot, and will end up being put with the others who failed the grade over in the same corner where the nonexistent God is already standing

510

in the spirit of reeducation, everyone is driven out daily to work somewhere or other. In neat formation, you leave the camp, you leave your children and the invalids, if there are any, to fend for themselves, and you work until you can barely put one foot in front of the other. The children go out and stand in front of the barrack, all seven of the camp’s children, which is us, they wait until you march out with the others in the direction of the ferma, seven rickety, knock-kneed children, the pale glow of their swollen knees stays with you until you are far away. At the end of the day you need somehow to get back to these children, but by then you haven’t the strength to walk, your ability to put one foot in front of the other has evaporated, to put one foot in front of the other, that’s right, it’s become a fixed phrase, it would be good to manage at least that till the end of the day, and to make it back home

511

lean on me, ma’am, urges Professor Balotă, offering himself to her, now then, up you come, coaxes Madam Nadia the pilot, who, gripping both her hands, pulls our mother up from the edge of the ditch, you needn’t worry about Nicu, Júlia, I should know, adds Nadia and laughs. Nicu Balotă goes bright red, he suddenly has no idea how to take hold of our incapacitated mother. In the end, he decides on her waist, puts his arm around her and gently eases her toward him, that’s it, that’s it, says Madam Nadia, beautifully done, and to think I’d given up on you completely, Nicu dear

512

our mother had a horror of being touched by any man she didn’t know, any man other than our father. We couldn’t begin to imagine how she had touched our father when he was still unknown to her, and she to him, this unanswered question led us to the possibility of our having been born of a virgin, all seven of us were virgin births, no question, and what’s more, we increasingly had to reckon with the probability that our mother’s own conception had been immaculate too

513

our mother finds it difficult to expose her chest, for example, before Romulus the medic, and when he places his naked ear against her naked skin, the little blood she has remaining drains from her face, picture a stethoscope, ma’am, when you see my ear, Romulus the medic tells our shrinking mother encouragingly, and there spreads across her face that childlike, boundless beauty of hers, and truly, a miracle is taking place, Romulus’s ear is pleasantly cool, like the eardrum of a stethoscope, though it could have been red-hot like our father’s. Our mother is visibly reassured by this metallic coldness, people have been created in such a way that they cannot listen to their own hearts

Our mother is visibly reassured by this metallic coldness, people have been created in such a way that they cannot listen to their own hearts.

514

oh yes, it’s God she ought to be leaning on at this point, thinks our mother on the edge of the ditch, but then God would have to exist. That would most definitely be the solution, if He were here in the camp and she could lean on Him, and it’s no excuse to say the reason he’s not here is because He’s everywhere, everywhere is not the same as nowhere. Whatever the case, it’s possible she would feel less horror at God’s deathly touch than at Professor Balotă’s, but she’d also settle for Abraham’s encircling arm, to be quite precise, for Abraham’s unfathomably extensive bosom into which the angels took the vagrant Lazarus all covered in sores when he handed his soul back to the Creator, the same Creator who, as we have seen, is so clumsy in His handling of the affairs of the poor, and who doesn’t exist of course, a fact that has now come to our attention too, by way of the new Party decree from Bucharest promulgated in the camp

515

Professor Balotă speaks Hungarian to our mother, he understands our language too, and at least as well as Dukát the Franciscan. Mr. Pali Făgăşan can also handle Hungarian to some extent, when he puts words together, he makes pretty good sense, he butchers Hungarian, says our firstborn sibling Feri, but I’m puzzled by this butchering of Hungarians because Mr. Făgăşan the radio repair man is especially fond of us, he definitely isn’t butchering the handful of Hungarians there are here. Now Marin the pickpurse and Livezeanu, they’d butcher them soon as touch them, but then they beat anyone black and blue who gets in their way, doesn’t matter if they’re Hungarian or Romanian, or Russian, like Nadia or a Jew, like Saul Făgăşan, or a Lipovan, like the eternally drunk Danube fishermen, as for us, says brother Feri, we butcher Romanian. What does he mean, we butcher Romanians, tell me a single one we’ve butchered lately or ever for that matter. I don’t like any of this, but that’s not important, I’ll understand this too, when the time comes, and if I don’t, then I don’t

Mr. Făgăşan the radio repair man is especially fond of us, he definitely isn’t butchering the handful of Hungarians there are here.

516

Madam Nadia speaks to us children in Romanian, to my mother, though, who can’t speak Romanian despite all her best efforts, she speaks German or French. Mother waves her hand dismissively, that’s all in the past, as useless as having a sixth finger. Nahdge-ah, my dear, imagine, I can’t for the life of me remember what the Italian for ceiling or window is

517

Nahdge-ah, that’s how our mother pronounces Nadia’s name, and this sweet softening of the central sound magically makes Madam Nadia the pilot all the more beautiful. The language of captivity isn’t Hungarian, nor is it Romanian, says our mother, and least of all is it French or German. Now Major Livezeanu, he really does speak the language of captivity, and we, too, will be broken in somehow sooner or later. The country, they say, already speaks the brand-new language of captivity fluently, we’re the only ones who still haven’t learned it, that’s why we’ve washed up here in the camp, the best thing would be to regard our time here as an intensive language course, as time in a state captivity-language school

The country, they say, already speaks the brand-new language of captivity fluently, we’re the only ones who still haven’t learned it.

518

our mother has been assigned to work in an enormous granary, she has to shovel wheat from one end of the building to another and back again. Golden grains, dust rising and falling in the harsh sunlight and the sound of Mimi Vaida’s deep coffee-house singing voice: breathtaking, murderous beauty in the forty-degree heat of the Bărăgan, and this beauty does regularly actually relieve our mother of her breath. Every day, pain lurks in her chest, keen lightning bolts slice through her left arm, and for a while she is able only to hold the shovel in her right hand, she scrapes clumsily at the fresh, still-damp wheat, then, when she can’t stand it any longer, she goes out in front of the storehouse in search of shade, she ducks behind a burning-hot trailer and massages her chest over her heart with a damp rag, then somehow she pulls herself together and goes back to the steaming mounds of grain to shovel

519

think yourself lucky doamnă, they say to her, seeing how slowly she’s getting on, she’s got it pretty good, the granary’s one of the best places to work, she shouldn’t be fussy, but if she’s more interested in digging irrigation channels, the work Aurél the architect and Praporgescu the Lifeguard Commander have been assigned to, she only has to say, it can be arranged. The country’s coat of arms has golden ears of wheat twined around it, it’s a great honor to work on the ferma, and, well, manual labor liberates a person from spiritual torment, that’s why the poor are blessed, doesn’t she know. She ought to be grateful then, that she’s happier than she’s ever been, happier even than in the encircling arms of Livezeanu, perhaps. She should beat any thought of sabotage out of her mind and if that doesn’t work, they’ll be glad to step in and beat it out for her right away

520

in front of the barrack, Professor Balotă hands our mother back to us. Our mother can’t walk, just staggers, her feet weaving about like Livezeanu’s and Marin the pickpurse’s do when they’re drunk, she looks like she’s saying something over and over, but no sound comes out and we have no idea who this continual stream of talk is directed at, she looks at us, counts us up, is glad to see us, to see that we’re there all seven of us, and heaves a sigh of relief. Nadia looks in for a short while and says something to the sisters. Sister Lídia and Sister Máriamagdolna get the tin bath out. Us boys have to go outside the hut, we stand around at a loss, listening to the water sloshing onto our mother’s depleting body

521

soon Nényu turns up too, on Romulus the medic’s advice, she has stolen some nice-looking apples from the model farm for our mother’s haphazardly skipping heart, she wipes them carefully, then pushes shiny iron nails into their flesh. When the apples have absorbed the iron, she grates two of them, stirs the fresh, iron-soaked, rust-red apple-flesh into some crumbled rusk, and after the bath, spoons it into our feebly protesting mother

Translation from the Hungarian