Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

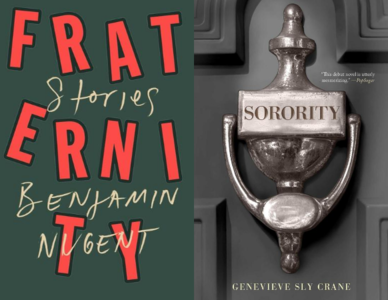

What lengths will we go to in order to belong? To be part of something exclusive? To be part of a sisterhood or brotherhood? That’s the searing question that authors Benjamin Nugent and Genevieve Sly Crane try to answer in their books about college Greek life.

Nugent’s Fraternity, a collection of linked short stories about some Delta Zeta Chi bros, tackles performative masculinity, existential crises, and brotherhood. In every story, a palpable sense of loneliness fuels the actions of the characters.

Crane was the pledge mistress of a sorority at the University of Massachusetts. Her novel Sorority follows the aftermath of the death of a sister, Margot. From hazing to eating disorders to sexual assault, Crane opens the closed-doors of life at a sorority with each chapter told from the perspective of a different sister.

Both Sorority and Fraternity take place at lightly fictionalized versions of the University of Massachusetts Amherst; Crane attended UMass as an undergraduate, and Nugent grew up ten minutes from campus. For Electric Literature, they talked about writing fiction set in a widely reviled subculture and using Greek life as a way of exploring questions about gender, misogyny, and privilege.

Benjamin Nugent: One of the things I love about Sorority is how unapologetic it is about how thrilling life in a troubling and politically objectionable subculture can be.

What are your feelings about showing us the pleasures, often perverse pleasures, of a subculture people are actively trying to shut down? [Editor’s note: As discussions of racism, inequality, and exclusion gain ground, the Greek system has been criticized for racist and misogynistic practices.]

Greek life exudes this simultaneous surge of degradation and power in deciding worthiness.

Genevieve Sly Crane: I felt compelled to write Sorority because the toxic approval system of Greek life marked me in a way that I couldn’t fully verbalize until I put it into fiction. Greek life, particularly rush (both as a sister and as a pledge), exudes this simultaneous surge of degradation and power in deciding worthiness. During rush, there’s the terror of possible exclusion. As a sister, there’s the terror of realizing why you were chosen, plus the fight to keep that status, sometimes at the expense of sanity or health. When I became a sister, I wish I could say I’d had some sort of grand protest about the system. But I didn’t. Why? Because the system picked me. It included me. And getting that sort of approval gave me a high.

I wrote Sorority within ten years of graduating from college, but even as I wrote it knew it was the documentation of a dying era. There is no way that sorority life in its current iteration should survive. As much as I loved (and still love) some of the women I met in my house, and as much as I liked being a sorority sister, my responsibility now as a cis white woman is to shut up and listen to what current students—especially BIPOC voices—have to say about what they want out of Greek life, if they want it at all.

BN: I tried to write about fraternity life the way Faulkner wrote about Mississippi. Fraternities don’t deserve anything like the same level of notoriety as the Deep South in the early 20th century, but the same principle applies. Faulkner was smart enough to know that the political situation in Mississippi during his lifetime was an abomination, but it was the world he grew up in and he loved it fiercely. To recognize that there is horror and the sublime in a tightly knit community, and make the reader feel the horror and sublimity both, that was my goal. I think that’s a politically progressive mission for a writer. Even if you know that what people are doing is terrible, it can only help to understand them. And the only way to understand them is with the degree of attention that constitutes a kind of love.

The young women in Sorority fantasize about committing acts of violence against each other and sometimes do commit acts of violence against each other. It’s something that predates their joining a sorority. What are your thoughts on young-woman-on-young-woman violence? And how does sorority culture channel the violent rage that your characters, young women, experience for each other sometimes?

GSC: For whatever reason, I think women in general (maybe men, too?) have traditionally been taught that success (and in this case that can mean beauty, popularity, intelligence, relationships—all of it) is a finite resource, especially because as women we just “won’t be any better” than we are in our 20s. I don’t think I was ever explicitly told that I would have a limited window to be THE BEST but I believed it, and I knew that in order to the best, it had to come at the expense of someone else’s happiness or value. I don’t think sorority culture is necessarily the problem here; I think it’s just a vehicle for this ideology to be acted out. I am optimistic that this idea is dying out. Instagram has a whole lot of circulated platitudes these days about women supporting women, and I think my students are about a billion more times emotionally evolved than I was, so I’m hopeful that we can outgrow the trap.

BN: Is the sorority a place that brings people into a collective insanity, like a cult? Or a place that cures people of their delusions? Or both?

GSC: Oh, I definitely think any close-knit group is set up for frenzy. I just have an infant son and even the private mom groups on Facebook are echo chambers of parents saying something insane and then basking in the echo chamber while other parents assure them they are not, in fact, insane. Whenever someone asks me what Greek life is like, I’m like: “how familiar are you with the Stanford Prison Experiment?” But here’s the flipside: with the right people, sorority life is absolutely not insane. It’s affirming and supportive and completely lovely. And it changes every semester. You had a similar line in your book:

“I said that when the right guys are running a fraternity, it’s a place where people will tell you if you’re being an asshole…But if the wrong guys are running a fraternity it’s more like a barbarian tribe, where all that matters is whether you’re in it or not.”

Cults and clubs are such a great breeding ground for good fiction. Everything is heightened, but the silliness of the ritual can make it laughable in the right context. I look at your characters in Fraternity and think: of course a brother would drink piss out of a toilet bowl if asked. It’s revolting and hilarious, but why wouldn’t he? It’s a small price for love.

BN: I wanted to take the reader’s hand and say, come, let’s go see the supposedly indecent people, the indecent and conservative institutions that sit at the center of Amherst, the somewhat smug liberal college town where I grew up. That line, about the right guys vs. the wrong guys running a fraternity, is spoken by a former fraternity president who now lives in LA. He’s trying to convey that Hollywood and other hierarchical communities—avowedly liberal ones—can have the same dynamics as fraternities, the same pathological view of power and insider-ness. They can be abusive in the same ways. Far worse, we know from #MeToo.

My goal is to recognize that there is horror and the sublime in a tightly knit community, and to make the reader feel both. I think that’s a politically progressive mission for a writer.

GSC: From the other side of the fence, I’d look at the high schoolers of Amherst while I was at UMass, and I always wondered if our proximity to them somehow primed them to be a little more debaucherous or wild, as if our immorality could work through the town like an infection.

Do you see any benefit to being in a fraternity? More specifically—do you think any of your characters in Fraternity were “good men”?

BN: Definitely. The narrator of my story “God” is a closeted young gay man, and very kind, actually, and the reason he’s closeted is that being a member of his fraternity is great, for him. He loves everything about it, the bond he has with his brothers, the way they all come to him with their troubles. The frat house is a sexy place, for him, and pretty safe. He knows that if he’s truthful about his sexuality there’ll be a downward adjustment in intimacy, in his brothers’ willingness to open up to him. He hides his desires because there’s so much for him to lose.

GSC: There are two women in Fraternity who complete rites of passage and ascend to become more than sexual conquests. (I’m thinking of Claire and “God,” specifically.) Are they meant to illustrate how woman need to work harder to be considered “worthy” by the brothers, or is it just an extension of their own hazing?

BN: They do go through rites of passage, but they’re not evaluated according to the same system as men, by the men. It would never occur to most of the guys in Fraternity to think of a woman as having proven her worth or not proven her worth. They’re so nervous about their own performances in the company of women that it never occurs to them that the women are not just sitting there serenely judging them and evaluating them, that the women are on their own journeys full of suffering and transformation. It’s more fear and projection than objectification.

Frat boys have a tendency to incriminate themselves by filming themselves at their bad behavior. Did that ever happen at your sorority? Filming the house’s rituals and transgressions against common sense?

GSC: In “real life,” my chapter was incredibly secretive about its rituals. And it’s funny—Greek life feels like a game, but even now you still couldn’t pay me to confess what our rituals were. It’s less out of loyalty to the organization and more out of loyalty to the five or six women that I love so dearly from my time there. But I think if I didn’t have that sort of affection for my sisters—like maybe if I harbored some resentment—that it would be almost irresistible to document and leak secrets online. It would be an easy way to throw a middle finger at a system that can make you feel powerless.

BN: Is it fair to say that the girls in your sorority are more self-aware than the boys in my fraternity? The pledge mistress knows she is “love bombing” the pledges, behaving like a cult leader. The pledges raise objections among themselves, talk about quitting: “I don’t want to buy my friends” and so on. But they stay. That seems to be one of the particular poignancies of your book: The sisters know what is happening, what unspoken needs of theirs are being served, what the psychological mechanisms are that will keep them in place. But they stay. They know exactly what’s going on but they choose it.

GSC: Absolutely, and I think it’s because that’s what I experienced as real-life sister. Desire beat ethics. I did some things that I consciously knew were wrong. I did them because of something fiercely primal in me.