WASHINGTON — As Democratic committee chairs and their aides took up the task Wednesday of writing the legislation to enact President Joe Biden’s mammoth social spending bill, internal divisions over Medicare expansion and paid family leave were among the last remaining hurdles to a final deal, lawmakers said.

This followed a day of apparent progress, during which White House aides huddled with key Democrats on Capitol Hill and Senate Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders, an influential progressive, met privately with Biden at the White House.

Democrats in both chambers expressed optimism that a deal could be reached within days to satisfy its chief opposing factions: the party’s two most conservative senators on one side and a crucial bloc of House progressives on the other.

Biden is scheduled to depart Thursday for a week of summits in Europe, and it’s no secret that the White House wants some good news to share with the world during his trip.

Yet even as the party appeared united in their goal, several key players in the talks made statements Wednesday that directly contradicted what other members of the party were telling reporters.

A proposal to create a federal paid family and medical leave system was reportedly dropped from the bill on Wednesday afternoon, according to NBC News, citing sources familiar with the talks.

But the leading advocate for the leave plan, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., told reporters it was premature to say the plan was totally out, saying she intended to speak to Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., as soon as she could about it.

Paid family and sick leave was a central part of the promise Biden made during his 2020 presidential campaign to ease the financial burden on working families.

But Manchin sees it as an additional, unnecessary government benefit in the bill, one that raises the overall cost of the legislation.

Another plan — to have banks report cash-flow information to the IRS for accounts with more than $10,000 in nonwage deposits — was dropped from the bill around midday Wednesday, CNBC’s Kayla Tausche reported.

But on Wednesday afternoon, Rep. Richard Neal, D-Mass., chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, said the bank reporting plan was not being dropped, it was being “reworked” to apply only to people who make more than $400,000 a year.

The invisible line between individuals making under $400,000 a year and those making more than that is an important one to Biden. The president has repeatedly pledged that nothing in this bill would raise taxes on people “making less than $400,000 a year.”

Another late-breaking proposal, to tax the unrealized market gains of the very richest Americans – people reporting more than $100 million of income or holding more than $1 billion in assets – also began the day Wednesday on shaky ground, after several Democrats privately expressed opposition to it.

Manchin told reporters he thought the plan was “convoluted,” and its demise seemed all but assured.

Later in the day, however, Manchin insisted he was not opposed to singling out billionaires for additional taxes, he just preferred to call it a “patriotic tax,” not a “billionaire tax.”

“Everyone should pay,” he told NBC. “So if I was blessed to have all this money, and I’m thinking, ‘Well, if I get this tax accountant, I can get away from that.’ That’s not right. That’s not America. So I call it a Patriot, being a patriot or patriotic person.”

White House press secretary Jen Psaki said Wednesday that Biden “supports the billionaire tax.”

But what exactly this meant wasn’t clear, especially after Neal said Wednesday afternoon the House and Senate were considering an alternative to the plan: a 3% surtax on individuals with incomes in excess of $10 million.

Still, the lead senator behind the original billionaire asset tax, Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden, D-Ore., insisted his plan wasn’t dead.

In a week of uncertainties, there was at least one new plan that won universal support among Democrats: a new 15% minimum tax on corporate book income, which would apply only to companies that reported over $1 billion in income for three straight years.

Potential sources of revenue to pay for the bill received new attention this week after Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., announced in mid-October that she would not support a longstanding plan to generate revenues by raising the corporate income tax rate and the top individual tax bracket rate.

Democrats need the votes of all 50 senators in their caucus to pass any bill, so Sinema’s announcement left the party scrambling.

Another sign of progress Wednesday occurred in the House, where a Senate-passed bipartisan infrastructure bill is languishing until a key bloc of progressive Democrats agree to vote for it.

The progressives have so far said they will not back the infrastructure bill until the Senate writes and ostensibly passes the other half of Biden’s domestic agenda, the social spending bill. To become law, that bill will rely on a complex legislative process known as budget reconciliation.

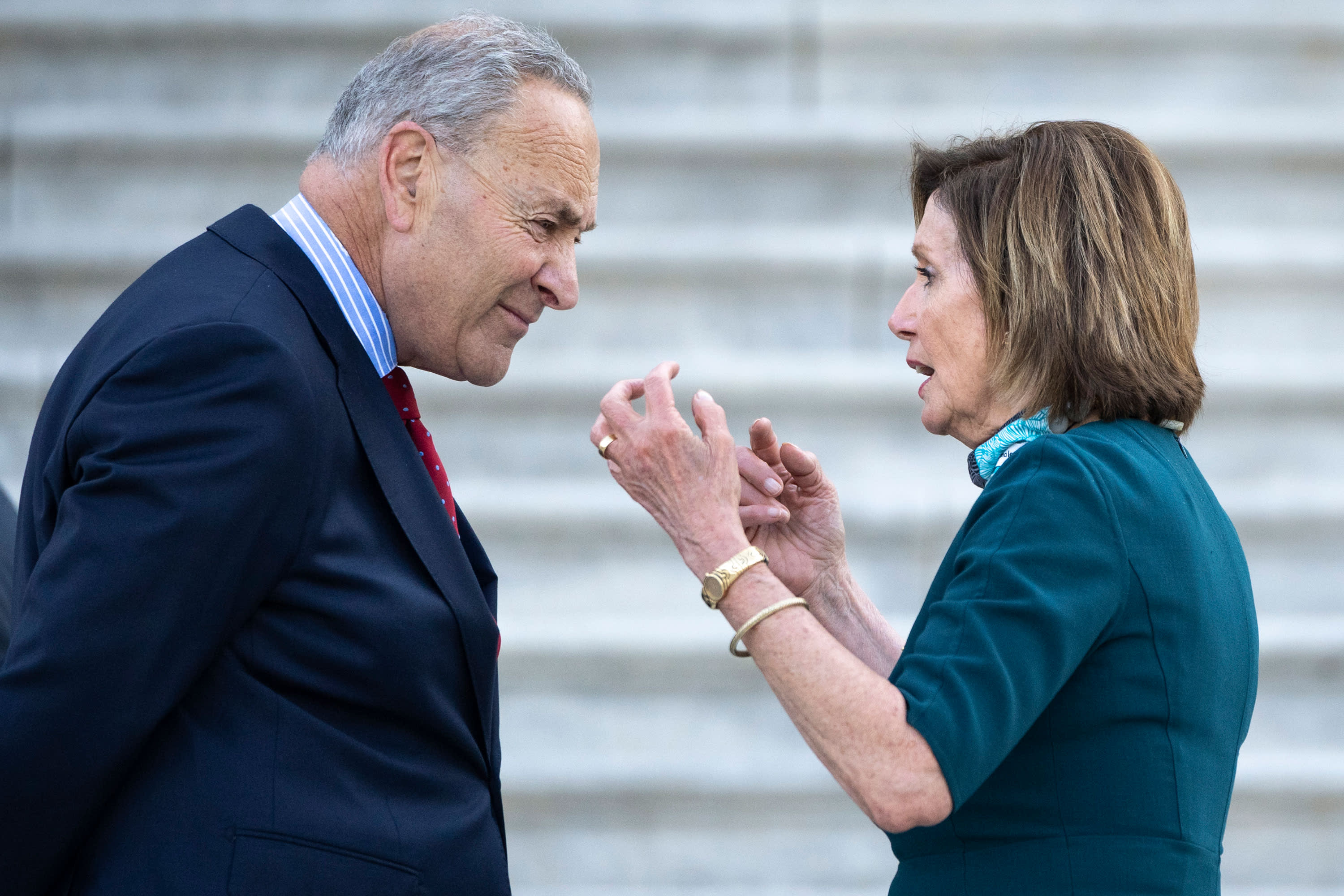

On Wednesday, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced the first step in this reconciliation process, a hearing in the House Rules Committee on Thursday to establish the specific steps and timeline for considering the reconciliation measure.

At the time Pelosi made the announcement, however, there did not yet exist an actual social spending bill for the House to consider.

While many of the agreed-upon pieces of the legislation had already been drafted in stand-alone form, they had not been woven into the bigger pieces of a bill. Pelosi reportedly instructed committee chairs on Wednesday to begin that work.

Of course, many of the thorniest issues were still being negotiated and cannot be drafted until they are resolved.

On Tuesday evening, the two most conservative Democratic senators, Manchin and Sinema, went to the White House for a private meeting with Biden in the Oval Office.

Senior White House negotiators traveled to the Capitol on Wednesday morning to meet again with Manchin and Sinema.

Following that meeting, which lasted nearly two hours, Sinema told reporters the talks were “doing great, making progress.”

As of Wednesday evening, Medicare loomed as one of the biggest unresolved issues in the bill. Manchin opposes any expansion of the program, opposition he says is rooted in his concern about the program’s long-term financial viability. Medicare subsidizes health care for more than 60 million individuals over 65 years old.

Yet Manchin faces powerful opposition in his bid to get a Medicare expansion removed from the spending bill: Sanders, the progressive budget committee chairman who has championed the plan to expand Medicare coverage to include vision, hearing and dental care for recipients.

On Wednesday afternoon, Sanders had his own meeting with Biden at the White House, a clear sign that the independent senator from Vermont has a crucial role in the negotiations.

— CNBC’s Kayla Tausche contributed to this report.