Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

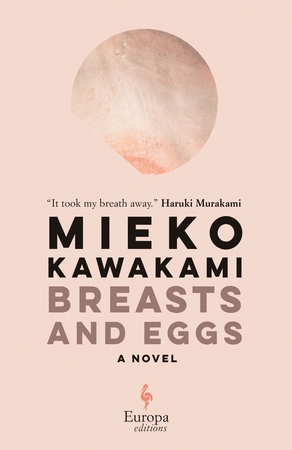

Though you’ve probably only learned Mieko Kawakami’s name recently, with the release of Breasts and Eggs from renowned indie press Europa Editions, she’s been a well-known figure in the Japanese literary world for several years. Haruki Murakami called her his favorite young novelist, and the novella that became Breasts and Eggs was the winner of the prestigious Akutagawa prize. The novel is Kawakami’s first translated into English, as well as the first of a three-book deal with Europa. In Japan, she’s also a pop singer and popular blogger. In fact, the book began as a series of blog posts years ago.

Breasts and Eggs is presented in two sections. The shorter, novella-length section of the book centers around Natsuko and her sister, Makiko, as well as Makiko’s daughter Midoriko. Makiko and her daughter are visiting Natsuko from the more rural Osaka, and Makiko has come into the city to explore her options for breast implants. Though she works as a waitress and is a single mother, she’s set on breast implants as both a physical and mental manifestation of a femininity she can’t grasp. Natsuko doesn’t necessarily approve of her sister’s desire, but she also doesn’t interfere. Over the course of a few days, the personalities of the three women clash with their desires for their bodies and their minds, creating a simmering atmosphere of resentment and ambition.

The second, much lengthier section finds Natsuko ten years later, with a well-regarded novel, and confronting her own relationship with intimacy, sexuality, and fertility. This part of the novel is more experimental, and heavier on moral arguments. As Natsuko explores her desire for a child, and her options for having one considering that she’s repulsed by sexual contact, she gets involved with a community of people who were born from sperm donors. All the while, she questions whether she actually wants the child she is considering, and what it means to want a child in the first place.

Kawakami was attempting an ambitious project with this novel: to question the role and function of the female body and how it is interpreted in society, through the lens of one woman with an unconventional path. We spoke via email about the role of the literary industry in the novel and the complex arguments the characters undertake with regard to fertility.

Translated by Hitomi Yoshio

Rebecca Schuh: I loved how specifically Mieko charted the trajectory of Natsu’s writing career. What made you interested in showing the ins and outs of the literary industry to a broader audience?

Mieko Kawakami: It wasn’t my intention to write a kind of tell-all story about the literary industry, but when I set out to write seriously about the life of the protagonist Natsuko and the problems she faced in her life, it became essential to write about aspects of her writing career. The novel is about people who are drawn to things that are not of their own choosing—the urge for artistic creativity, sexual identity, the body—so perhaps that’s why, in that sense too, it became such a symbolic scene.

RS: What inspired you to write about this triangle of struggles, with breast augmentation and fertility and sex?

The body is something that cannot be separated from the self, and at the same time, it is the closest other.

MK: I wanted to write responsibly about the cycle of how we are born, how we live and die, through the lens of one woman’s life. What happens to the body, and all the other aspects, during our lifetime? Breasts and eggs, as the title implies, are organs that are symbolic but also realities of women in terms of gender and sex. The body is something that cannot be separated from the self, and at the same time, it is the closest other. For me, writing relentlessly about the body—which is the ultimate personal experience—from all angles, is connected to writing and observing society and the distant unknown.

I had no intention of portraying what is generally perceived as the conflicts of a thirty-something woman. As women, we are often measured and defined by our gender and social roles such as motherhood, wifehood, and certain occupations and positions, existing merely as numbers in various statistics and data in society. But in reality, each one of us is an irreplaceable individual. There are parts of us that cannot be labeled, feelings that cannot be explained, and memories and circumstances that cannot be shared. This is called individuality, but these things can also be labeled as “abnormal” just because it is out of line with the norm. Heterosexuality, marriage, motherhood, a stable life… if you are not following this linear track, then you have no right to become a parent. In this sense, Natsuko Natsume does not meet the social conditions for encountering her own child. But she thinks, and she acts. Without borrowing the framework of a fable or science fiction, I wanted to write a story about one woman’s survival—a woman with no social status or power—within the same world order that the reader inhabits.

RS: I was interested in Yuriko’s theory about the parental ego in the realm of donor conception, that parents care as much about their own fulfillment as they do about the well-being of children generally. She believes that parenting is fundamentally selfish, since the child is not asking to be born, and, by her estimation, 1 in 5 children are born into a life of pain. Do you think her theory has any credence, or is it mostly a reflection of Yuriko’s tragic past?

MK: I understand Yuriko’s position well. Anti-natalism, or the idea that we should desist from procreating (note: for those who are already born, it is an imperative to live a virtuous life), has been eloquently expressed by Schopenhauer and Cioran, and more recently elaborated on by the philosopher David Benatar. However, I believe that anti-natalism from the perspective of women, whose bodies have the ability to give birth, is fundamentally different from their claims. Yuriko Zen has a painful past, but she doesn’t base her beliefs entirely on her experience alone. She truly believes that it is a tremendous violence to force a “body,” which is the premise of “pain,” to suddenly come into existence. Is childbirth really something to be celebrated wholeheartedly? The question Yuriko poses is an essential ethical problem that must be considered as reproductive technologies continue to be developed.

RS: What inspired your interest in donor conception that became such a deep throughline of the book?

The birth of a child often becomes a tool to perpetuate the model of normalcy.

MK: It is often said that the Japanese do not have a religion, but what plays its role instead is patriarchy and the pressure to conform. Most families are created on the basis of blood ties, and the hurdles of adoption are astronomical. There is little diversity in terms of family structure. The ethics and acceptance of sperm donation (also called artificial insemination with donor sperm, or AID) are completely different in the West and in Japan. The birth of a child often becomes a tool to perpetuate the model of normalcy, for the sake of the parents or the family name, and the whole ordeal is treated with absolute secrecy. I was moved when I read the accounts of those born through AID and to learn of their suffering and unceasing fears. And it’s not just men who enforce these oppressive norms. Many women have also internalized these patriarchal structures.

RS: Can you talk a little bit about your life as a writer?

MK: I grew up in a poor single-mother household. All through my teenage years, I’ve had to lie about my age so that I could work various jobs—as a restaurant server, dental assistant, dishwasher, cashier, factory worker, bar hostess, and many others. Now that I write as a living, I’m surrounded by highly educated intellectuals who grew up doused in cultural and economic capital, and I often feel dizzy because I cannot comprehend that we have inhabited the same world. I happened to be able to make a living through writing, but I cannot help feeling incredibly lucky. First of all, I was blessed with a body healthy enough to survive, a resilient personality, and a mother who was a loving, altruistic, and truly wonderful human being. I am grateful to her from the bottom of my heart for teaching me how to think, and to overcome any hardship with laughter. No matter where I am or what I write about, I will never forget the town where I grew up and the people who were there.

RS: Who are your favorite writers or artistic influences?

MK: There are many, but I learned from Haruki Murakami the intricacy of description, the manipulation of information inside a novel, and the persistence and perseverance toward the act of writing. He is an enormous writer for me. In a similar way, the artist Hokusai always gives me inspiration and courage. He’s an artist who produced so many works throughout his life with every fiber of his being, creating incredible masterpieces in his seventies while lamenting that he could not draw even a single cat to his satisfaction. At the age of 90, he is known to have said on his deathbed, “If I had five more years, I could become a true artist.” I want to live and produce work that lives up to their standards.