Even though they appear to have a lot to say about the historical, political, cultural, and literary situation of the Middle East, Kurdish female novelists and short-story writers have remained unknown to an international readership and hence have not been included in the case studies of scholars in the aforementioned fields. We know that Kurds have played a significant role in the history of the Middle East, and rarely has there been a historical and political event in the past decades—even past centuries—in the Middle East in which Kurds have not been in one way or another involved. A review of the history of the Middle East in the past century very significantly delineates this. One of these women writers is Chinur Sa’idi who, having majored in philosophy and living as a human rights activist in the past decade, has written three collections of short stories.

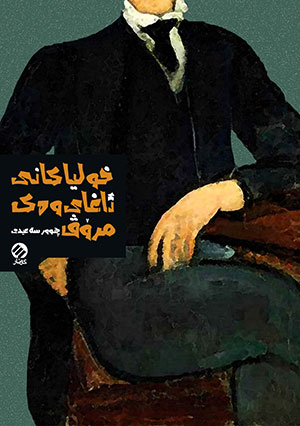

Sa’idi has published three collections of short stories: in 2006, 2012, and 2018. One can see a line of development in her career that shows she has become more professional and concerned about the significant historical, political, and cultural issues in the area. In her most recent collection, The Hobbies of Mr. Like-a-Man (Gotar, 2018), she has come to be more unified, touching, and emotive. The short stories of this collection contain various meaningful layers and levels, with a sad, pessimistic tone mostly narrated by unique female narrators. These touching life narrations belong to single moms, divorced women, women who have been sexually assaulted and raped, those that have been betrayed or live alone. If we think of only one single title for all these stories, it would be the stories of Kurdish women’s hardships and isolation. This title is more than just about feeling lonely; it reveals the community’s pressure, depression, and finally death. Here are life stories by women narrators about their painful obstacles and problems as a divorced lady or a raped girl. There is no strong, brave protagonist here; they are mostly miserable, anxious female narrators who are forced to live in their gloomy and sickening society.

Sa’idi has published three collections of short stories: in 2006, 2012, and 2018. One can see a line of development in her career that shows she has become more professional and concerned about the significant historical, political, and cultural issues in the area. In her most recent collection, The Hobbies of Mr. Like-a-Man (Gotar, 2018), she has come to be more unified, touching, and emotive. The short stories of this collection contain various meaningful layers and levels, with a sad, pessimistic tone mostly narrated by unique female narrators. These touching life narrations belong to single moms, divorced women, women who have been sexually assaulted and raped, those that have been betrayed or live alone. If we think of only one single title for all these stories, it would be the stories of Kurdish women’s hardships and isolation. This title is more than just about feeling lonely; it reveals the community’s pressure, depression, and finally death. Here are life stories by women narrators about their painful obstacles and problems as a divorced lady or a raped girl. There is no strong, brave protagonist here; they are mostly miserable, anxious female narrators who are forced to live in their gloomy and sickening society.

All three of Sa’idi’s story collections contain feministic themes and motifs in a context of war and depression that has devastated the Middle East in the past decades. Being located on the borders between Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria, the Kurds have particularly tasted war, devastation, and destruction more than any other ethnicity in the area. We know that the ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) attack on the Kurdish cities in Iraq and their brutal execution of men and imprisonment of women have created a traumatic effect in the minds of Kurdish women, in particular. ISIL’s attitude toward the imprisoned women as commodities has created a painful memory in the minds of Kurdish women. In one of the stories of this collection, Sa’idi refers to the genocide of Yazidis, when thousands of Yazidi women and girls were forced into sexual slavery by the Islamic State, just like Salmā, the protagonist of the story whose parents and siblings were beheaded by ISIL as cruelly as possible. Salmā is no longer a normal sixteen-year-old girl, but a pregnant slave who has endured many hardships. The story is dedicated to Firās Mirzā (a historical figure in her fictional world) who freed more than a hundred Yazidi girls by buying them from ISIL. These girls have mostly committed suicide as they have never been able to overcome this trauma and come back to their community. Although the story has an open ending, it seems that the same thing is going to happen to Salmā.

Sa’idi stands up for all women in her community, speaks up, and uses her platform to bring back women’s voices to be heard.

Chinur Sa’idi has tried to write about such experiences. She has even seen and talked to the Yazidi women in the Kurdish city of Sinjar. Moreover, she has tried to write about a community in which there is still sexism in language. A story in the collection that shows how Kurdish women have suffered from within their community is “Fatāne’s Wounded Songs,” which is about Fatāne Validi (a real female singer in the city of Sanandaj, the central city of Kurdistan Province in Iran), who has been marginalized and pushed into isolation because of being a singer. The story is about the miseries and hardships such women are to suffer if they want to practice such things. She writes about a community in which there are still such sexist comments as “if women were good, we’d have a female philosopher.” Sa’idi stands up for all women in her community, speaks up, and uses her platform to bring back women’s voices to be heard; the purpose of her short stories is to help bring the light to this dark situation of women in the Kurdish community.

Reading Sa’idi’s collection of short stories will shed light on some aspects of Kurdish community as an important part of the larger Middle Eastern society that has not been represented in the common reports and news stories, nor even recorded in historical texts. What makes the book worthy is the fact that it goes beyond reportage and the historical record in the life of Kurds; she has selected a combination of fiction and reality as a medium for representation in order to make the traumatic situation visible to a larger international readership. The real historical characters along with fictional ones make the boundary between fact and fiction blurry and hence give an ironic image of the situation.

University of Kurdistan