If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

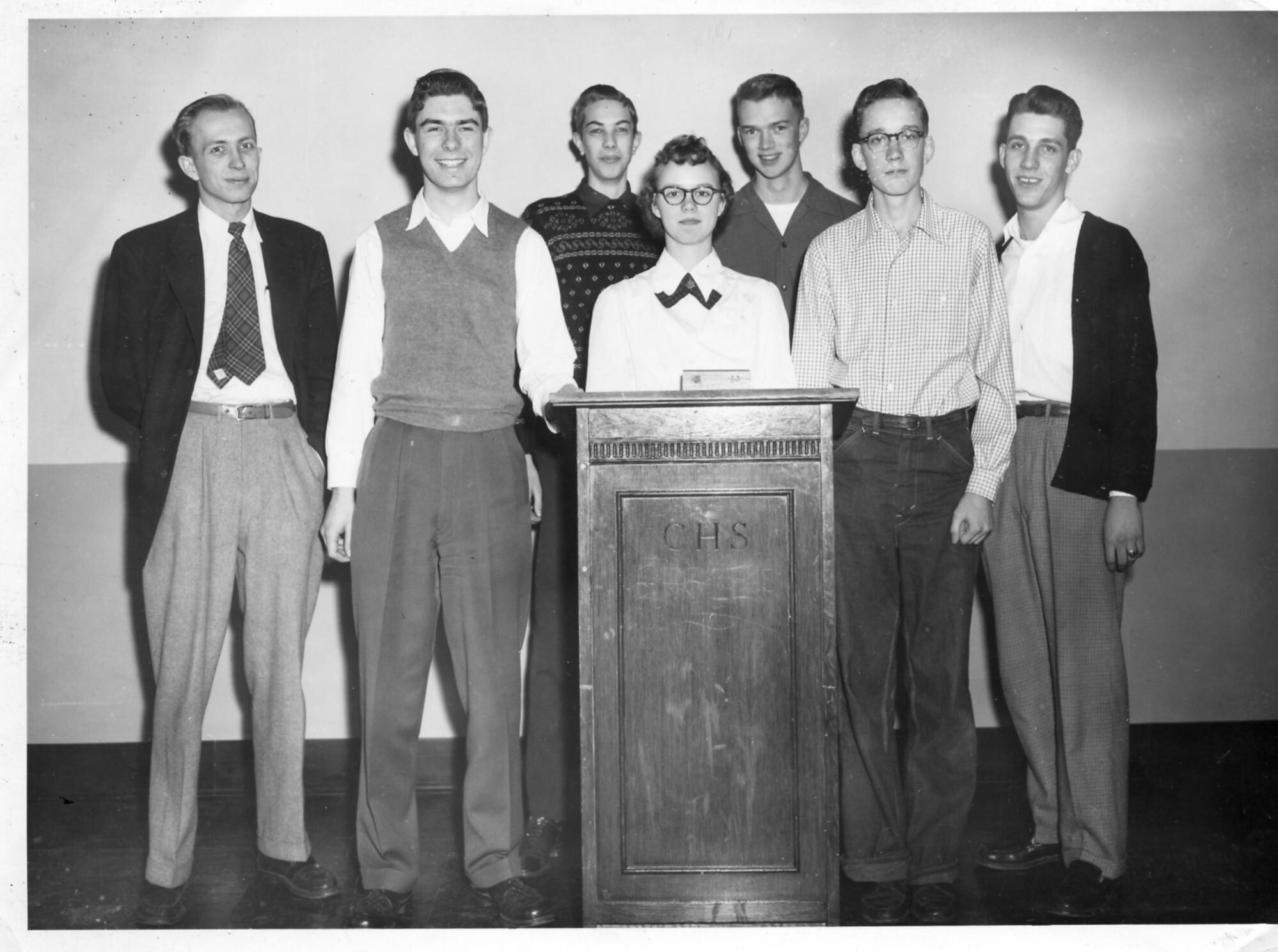

“America is adolescence without end,” Ben Lerner writes in The Topeka School. His witty, revelatory novel follows the Gordon Family—Adam, a high school debate star, and his parents—in 1997 Kansas. The book is dense with themes, but none more haunting than the question of toxic masculinity’s source. While Lerner offers no straightforward answer—nothing about this book is straightforward—the setting itself is a clue. Do high school debate tournaments provide hints for what will become of its champions?

The Topeka School stayed with me for months. In the weeks after reading, I relived every infuriating experience from my own high school debate league. The boy who explained that the distribution of semi-finalists was designed to ensure a girl must make it to finals, because without interference, she wouldn’t get there. The boy who suggested Hillary Clinton was too angry to be President, and then, when I countered, asserted I was too angry to be the victor. The judge who docked points from me because I was “too emotional” (I wasn’t even crying!).

It’s a scary thing to imbue a young boy with confidence he hasn’t yet had the time to earn.

I knew Lerner’s characters. I’d debated them in high school and college. It’s a scary thing to imbue a young boy with confidence he hasn’t yet had the time to earn. As Lerner writes of Adam and his classmates, “they are told constantly…that they are individuals, rugged even, but in fact they are emptied out, isolate, mass men without a mass, although they’re not men, obviously, but boys, perpetual boys, Peter Pans, man-children.”

Several of Lerner’s boys turn alt-right years in the future, and I wondered if the same became of any of my former debate rivals. What happened to the diligent, smart 17-year-old boy who won the national championship arguing against punitive measures for the investment banks that perpetrated the 2008 financial crisis? And the one who equated affirmative action to fascism? Has he changed his mind, or had he already become his final form? Is he a lawyer, looking towards a future run for office, or did he leave politics behind? 20 years from now, when I’m watching their Supreme Court nominations, will they be Kavanaughs?

By the end of October 2020, I’d Googled each and every one of my former debate competitors to determine which way they were voting. As I figured it, nothing about a Biden vote suggests someone has turned out okay, but a Trump vote screams something went wrong. I scrolled the profiles of the few rogue Trump supporters. I read their arguments. I reread their arguments. I screenshotted their arguments and sent them to dozens of group chats. “Can you believe this????” I’d write, as though it was shocking to know one of the 74 million Trump voters. But the thing is, it was. Encountering a Trump fan at some point is a statistical likelihood, but it’s eerie when it’s someone from your formative years—how could you see the world so differently when you had started in the same place? How did the girl who first explained to you the mechanics of a blow job end up defending the police? She used to be fun! It was even eerier to see this uncritical embrace of our fascist President from the people with whom I’d learned to think critically about politics. My old debate pals used skills I’d watched them develop as teenagers to defend our ignoble Commander-in-Chief.

By 2021, I had become a curious observer, but I must admit that in high school, I was one of Lerner’s boys. I always thought I was right. I was (and am) a privileged white person who believed my opinion mattered more than it did. I once hid a competitors’ shoes to prevent him from getting to the round on time (in my defense, he shouldn’t have taken them off). Another school’s coach once yelled at me for openly talking shit about a competitor. His exact words were “we never root for someone else to lose.” (I was confused—in a world where only one can win, isn’t rooting for yourself the same as is rooting for everyone else to lose?) No one I knew in high school would have been surprised if I’d sought public office, although I consider it a great act of service that I have not.

Still, my membership into their club—not so much a friend but rather a person worthy of being treated as a threat—depended more on my assimilation than anything else. It was still a boys’ club, with or without me, and toxic masculinity depends on the compliance of some women—white women in particular. Arrogance and an inability to admit error aren’t unique to men, but they are more common. Like the U.S. Senate, my debate league was mostly boys. I’d argue it’s not a stretch to attribute much of the toxicity to their nascent masculinity.

I didn’t need to wait long to meet another of Lerner’s boys. On January 6th, 2021, violent protesters stormed the Capitol to protest the results of our election. Six Republican senators voted to overturn the results, and on that day, our nation minted a new villain—Missouri Senator Josh Hawley.

Josh Hawley is no ordinary Josh. Like Lerner’s characters, his familiarity shook me: his ability to talk around an issue, his champion high school debate record, his smug confidence. Look at his Wikipedia page—he’s literally sneering in the photo. It took no effort to picture him as a 17-year-old cross-examining me in the finals, lamenting my ill-preparedness, leering just the way he does on FOX News.

Of course, debate is not the only high school activity that breeds overconfident youngsters, and Hawley is far from the only right-wing senator with a high school debate record. You can’t throw a stone in Washington without hitting an Ivy-League-educated right-wing senator who cut their teeth on high school debate, although I’d encourage you to try. Ted Cruz, a champion Princeton debater, has a similar background, but he simply didn’t strike the same spooky chord as Hawley. Perhaps it’s that Cruz is older, so he feels more distant. Hawley is disturbingly boyish, and the familiarity haunts me – his hairline cannot recede fast enough for him to become a stranger. Perhaps it’s that I was given more time to ease into Cruz’s villainy. With a personality like his, Hawley should have had the courtesy to offer us some warm-up time! Instead, he turned himself into a household name overnight by opposing Democracy in a country notoriously obsessed with Democracy. In the most toxically-masculine-high-school-debate move of all, he took an unwavering line on an unpopular position to turn the spotlight squarely on him.

You can’t throw a stone in Washington without hitting an Ivy-League-educated right-wing senator who cut their teeth on high school debate, although I’d encourage you to try.

Teenage debaters do this tactically. In the climax of The Topeka School, Adam competes against a team from Austin. His opponent employs a tool not common to their category: the spread, in which you speak at a pace of several hundred words per minute so the other team cannot possibly refute every argument. Some judges love the spread, others hate it, but either way, it’s a strategy that allows the debater to center himself (or herself – but probably himself). The gamble pays off: Adam is caught off guard, and the spreaders win. Hawley essentially did the same—he intentionally confused us to garner attention very quickly. He took a shocking viewpoint to force the conversation further to his side, when in truth, his position was so unreasonable we should never have needed to address it. Whether or not he’s won remains to be seen.

Hawley may well have learned his behavior as a Missouri debate star in the 1990s, one state over from Adam. Early in The Topeka School, Lerner describes a debate round in which Adam scores an easy victory: “Adam had no idea if what he was saying was true…The key was to narrate participation in debate as a form of linguistic combat; the key was to be a bully, quick and vicious.” Debate is less about figuring out what you think is right than it is about proving someone else wrong. It doesn’t teach values—there is no discussion of what’s actually good or bad, only that such a dichotomy exists at all.

High school debaters take fixed positions on issues they can’t possibly fully comprehend, whose outcomes they’ll never see. The judge—likely a parent who doesn’t have the answers either—has a matter of minutes to decide who’s right. Aggression wins. Volume wins. Confidence wins. Being right doesn’t win—if a high schooler knew how to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, we’d surely live in a very different world.

Of course, kids should grapple with our social issues. They’re our only hope. But we don’t have to teach them the other side is always wrong, and that truth is determined by persuasive elocution. We can teach them to hold opposing viewpoints in their head at once. We can teach them to be kind. We can teach them that they don’t yet have all the answers. It’s terrifying that we teach kids how to argue before we teach them how to empathize.

In debate’s defense, it teaches students to follow the rules—at least, as long as the power resides with the judge. In the most iconic image from the January insurrection, Hawley holds his fist in the air, saluting his supporters. This photo is an undeniable salute to white supremacists. But I saw something else, too. In debate, a fist in the air means “stop”—you’re out of time, and you’ll be disqualified if you continue. Hawley was, by all accounts, a successful debater. He stopped when he saw the fist. Now, he was using the fist to egg people on. What if the debate fist was the last rule he ever followed? In debate, if you don’t follow the rules, you lose. In politics, you can break all the rules (“laws”), and still be elected President of the United States. Hawley would listen to a debate judge who could bar him from the final round, but not the will of 81 million Americans.

It’s terrifying that we teach kids how to argue before we teach them how to empathize.

If a fist in the air reminds me of debate, a stop sign means something else to me, too. My freshman year of college, I was sexually assaulted by a boy on the Stanford Debate team. I said no, and he went forward. He was also a skilled debater; he respected the fist of a judge. When the judge had authority, his stop sign mattered. But mine did not. Boys who want to win know what rules they must follow. Those with power must be obeyed. Those without it can be ignored.

I may have just made the January 2021 insurrection about me (that’s sort of my thing), but I do think the fist is important. Wasn’t Hawley’s fist in the air a stop sign of his own? Stop counting votes. Stop respecting democracy. When did he stop obeying the signs of authority figures, and instead start issuing his own? Was it when he became a Senator, or the Missouri Attorney General, or was it long before that?

Not all former debaters turn into Josh Hawley, of course, and not all become sexual predators. Nor are white supremacy and sexual assault the only two ways to be bad, but they are significant both in their severity and in their frequency (case in point: Trump became President). Maybe there’s hope, though. Maybe we can find these boys at their forks in the road and prod them in the right direction, or at the very least, away from power. As Lerner writes of Adam’s young, right-wing debate coach, “one moment, Evanson struck him as a precocious young man, destined for the corridors of power—a conservative judge, a senator, the president of the NRA—and at other times Evanson seemed fated to drive sleeping debaters, sleeping drivelers, home from Junction City.” Perhaps this is the crux of it, the turning point. Go one way, and you might be okay. Turn the other, and you’re Josh Hawley.

The Topeka School doesn’t tell us, though, how its characters choose which way to go. The liberal Adam isn’t seduced by bad politics, but continues to treat other people poorly; the violent, future-MAGA fan Darren is dealing with cognitive challenges that complicate his behavior; the right-wing Evanson shows up after college, with only brief hints of his past. Without answers from Lerner on how his boys turned into his men, we must look elsewhere.

Hawley’s mentor, John Danforth, described supporting Josh Hawley as the “worst decision he ever made in his life.” Did Danforth really not know? Were there no clues? A former college classmate said of Hawley, “Most freshmen are on a journey to discover who they are and what strengths they have to offer the world, but Josh seemed to have already completed that process by the time he arrived at Stanford.” And that’s just the danger. In Hawley’s 2021 world, Donald Trump was President, and he was unwilling to consider another option. Was college too late? His signature on a friend’s eighth-grade yearbook chillingly reads “Josh Hawley, President 2024.” A 13-year-old wanting to be President isn’t terrible—a 13-year-old who has already become Josh Hawley is. 2024 is soon, but don’t rush it, Josh—you have the next 40 years to destroy us.

One genre of post-insurrection-Hawley-tweet that annoyed me most was the joke that he’s proof “idiots” can go to the top-tier universities, too. I’m not offended by the sentiment—I’m intimately aware that top universities are populated by people with a wide range of intellectual capacities. Rather, it’s the idea that Hawley is an “idiot” for having heinous political views. The word “idiot” is a dismissal (and one with an ableist history). “Idiots” aren’t scary. “Idiots” aren’t a threat. Hawley did not think Trump was the legal victor; he was making a bet on January 6th. And we should all be very afraid of whatever he’s betting on. Taking the wrong side and doubling down may have been impressive when he did it in high school, but now, it’s simply terrifying.

They know their power is fragile. They know they’re no better than anyone else, and they know we know.

I hope the past four years have made us keener to identify toxic masculinity early. Lerner agrees, writing, “If we’ve learned anything, it’s how dangerous that fragile masculinity can be.” The fragility is what makes it so toxic. That’s why the neo-Nazis in Charlottesville chanted, “Jews will not replace us,” why Republicans fight against affirmative action, why men fear the #MeToo movement. They know their power is fragile. They know they’re no better than anyone else, and they know we know.

The Topeka School points towards the roots of toxic masculinity, but it doesn’t offer all the answers. Josh Hawley is one version of what Lerner’s boys could grow up to be, but there are others. Lerner uses a high school debater to show us that language is no longer used for communication—it’s used as a weapon. If we’re going to give it to children, we must teach them to wield them responsibly, teach them to think through their positions before attempting to win with them. If we don’t, we may be looking at a whole lot more Josh Hawleys.