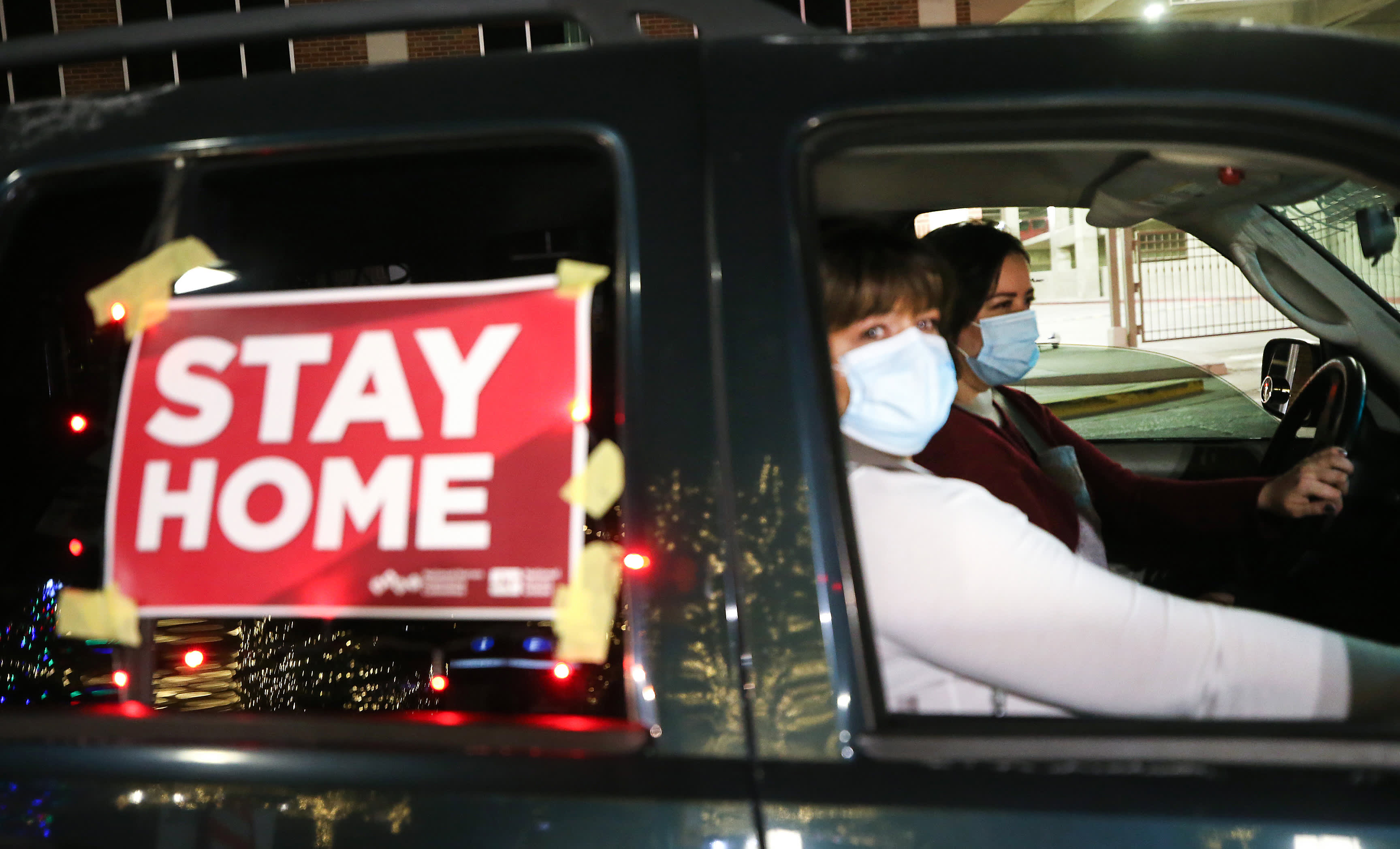

Nurses display a ‘Stay Home’ sign on their vehicle during a car caravan of nurses calling for people to remain home amid a surge of COVID-19 cases in El Paso on November 16, 2020 in El Paso, Texas.

Mario Tama | Getty Images

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Wednesday unveiled new quarantine guidance that allows some people to restrict their contact with others for less than the recommended 14-day period under certain circumstances.

The new advice was created to try to boost compliance with the quarantine guidelines, but some public health experts say the nation’s premier health agency was trying to solve the wrong problem. Instead of focusing on why people aren’t adhering to the guidelines, the agency focused on the rules themselves, which undermined the risk of exiting quarantine before 14 days, epidemiologists said.

“To me, this policy creates a false dichotomy, people won’t do 14 days so they need a shorter quarantine period,” Theresa Chapple, an epidemiologist, wrote on Twitter. “Instead, we could create wraparound services to support those quarantining and isolating.”

Rather than providing services such as free food delivery or even lost wage compensation to encourage compliance, the CDC’s decision to provide shorter, riskier alternatives to the 14-day quarantine sends the wrong message to the public, epidemiologists and health policy researchers told CNBC. It could serve as something of a permission slip to exit quarantine when there’s still a significant level of risk that the person remains infectious.

Representatives for the CDC did not provide comment in time for publication.

On Wednesday, CDC officials said the agency will continue to recommend all people exposed to Covid-19 quarantine for 14 days “as the best way to reduce the risk of spreading Covid-19.” However, they added that people exposed to the virus can exit quarantine after 10 days if they don’t have symptoms, or after just one week if they don’t have symptoms and test negative within 48 hours of the last day of quarantine.

Those 7- and 10-day options are riskier than the original 14-day quarantine, Dr. John Brooks, chief medical officer for CDC’s Covid-response, explained. He said ending a quarantine after 10 days without a negative test leads to about 1% risk of spreading the virus to others, but could be as high as 12%. After a seven-day quarantine with a negative test, there’s about a 5% chance of spreading the virus, he added, but that’s with an upper limit of about 10%.

‘Wraparound services’

Some epidemiologists said the CDC shouldn’t be endorsing a strategy that carries such risk, and they should instead provide more support for people to comply with the safest approach to quarantining.

Saskia Popescu, an epidemiologist and biodefense professor at George Mason University, said the CDC’s policy update underscores “the challenges in getting people to quarantine for 14 days.” She added that it “is a great example of the challenges we face in public health.”

“If you can get more people to quarantine for a lower period of time, is that better than fewer for the full 14 days?” she asked in an email to CNBC, adding that the CDC appears to have missed the bigger question. “How can we provide better support services to ensure people can quarantine for 14 days? Those wraparound services are so important and have gotten less attention despite their enormous efforts.”

Various cities and states have experimented with different forms of “wraparound services” meant to support people who need to quarantine. New York City, for example, will provide hotel rooms for people who need to quarantine, but live with others. But some epidemiologists and public health specialists have said the CDC could invoke its authority to implement federal services, like the agency did when it placed a moratorium on evictions earlier this year.

To be sure, some epidemiologists praised the CDC for taking a more practical approach to its quarantine recommendation. The data indicates that the overwhelming majority of patients are no longer infectious by day 10, and allowing people to exit quarantine then let’s them get back to work and provide for their dependents. But it doesn’t come without increased risk, as some will remain infectious past day 10.

‘What a sucker would do’

Ellie Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University, said the new guidance feels something like a compromise by the CDC, or a negotiating tactic. She added that if somebody wasn’t going to complete 14 days of quarantine, she’s not sure they would complete seven or 10 days, either.

“I think the recommendations are based on an idea that there are people who see 14 [days] as the rule and say, ‘I can’t do 14,’ so I’m not going to do any at all, and [the CDC] wants those people to know that seven [days] would be better than nothing,” she said in a phone interview. “But I don’t think that’s how the message is getting out.”

Murray said she’s concerned that some people are interpreting the guidance as saying that quarantining for 14 days is not that important, even though the CDC still says it’s the safest route. She said some people who have the resources to quarantine for 14 days, might now choose not to, because “that’s what a sucker would do. I’m going to do seven.”

“There is risk incurred by ending quarantine early,” she said. “That’s something that’s really important to get out and I think the real story here is that people are not getting that message.”

‘Get out of jail faster’

Dr. Jake Deutsch, co-founder and clinical director of Cure Urgent Care in New York City, said he’s concerned because the guidance appears to be “very subjective.” The CDC said the 10- and 7-day quarantine options are reserved for those without symptoms, but Deutsch said it’s unclear to patients what exactly Covid-19 symptoms are.

“When you start saying, ‘if you’re symptom free, now you can get out of jail faster,’ I just think that people are going to minimize their symptoms,” he said. “That sore throat, that’s a symptom. That little bit of congestion for some people, that’s a symptom. I see so many people that say, ‘Oh, it’s nothing.'”

Deutsch added that the guidance appears to be a classic case of disclosing too much information to patients, which he said can lead to confusion. The strategy does appear to be driven by a smart analysis of data, he said, but it could nonetheless be misinterpreted by the public.

“Anytime you give too much information to patients, it sort of stacks upon itself and becomes confusing,” he said. “That’s really what I see here and we’ve seen this unfortunately a number of times. The CDC has not been so well spoken.”