Jami Nakamura Lin begins with a warning: “In the presence of a story—if the story is a good one—time collapses.” This is precisely what she achieves in a genre-bending memoir that collapses past and present, personal and mythical. The Night Parade begins with her attempts to trace the origins of her bipolar disorder that first manifested in her inexplicable childhood rage. Despite her teacher’s suggestion of therapy, her father insists she is not depressed, until she experiences a major depressive episode at 17. But it’s not until Lin’s suicide attempt soon after—an event that amplifies the ripple effects of her mental illness on her family, including her younger sisters—that she is properly diagnosed and given medication.

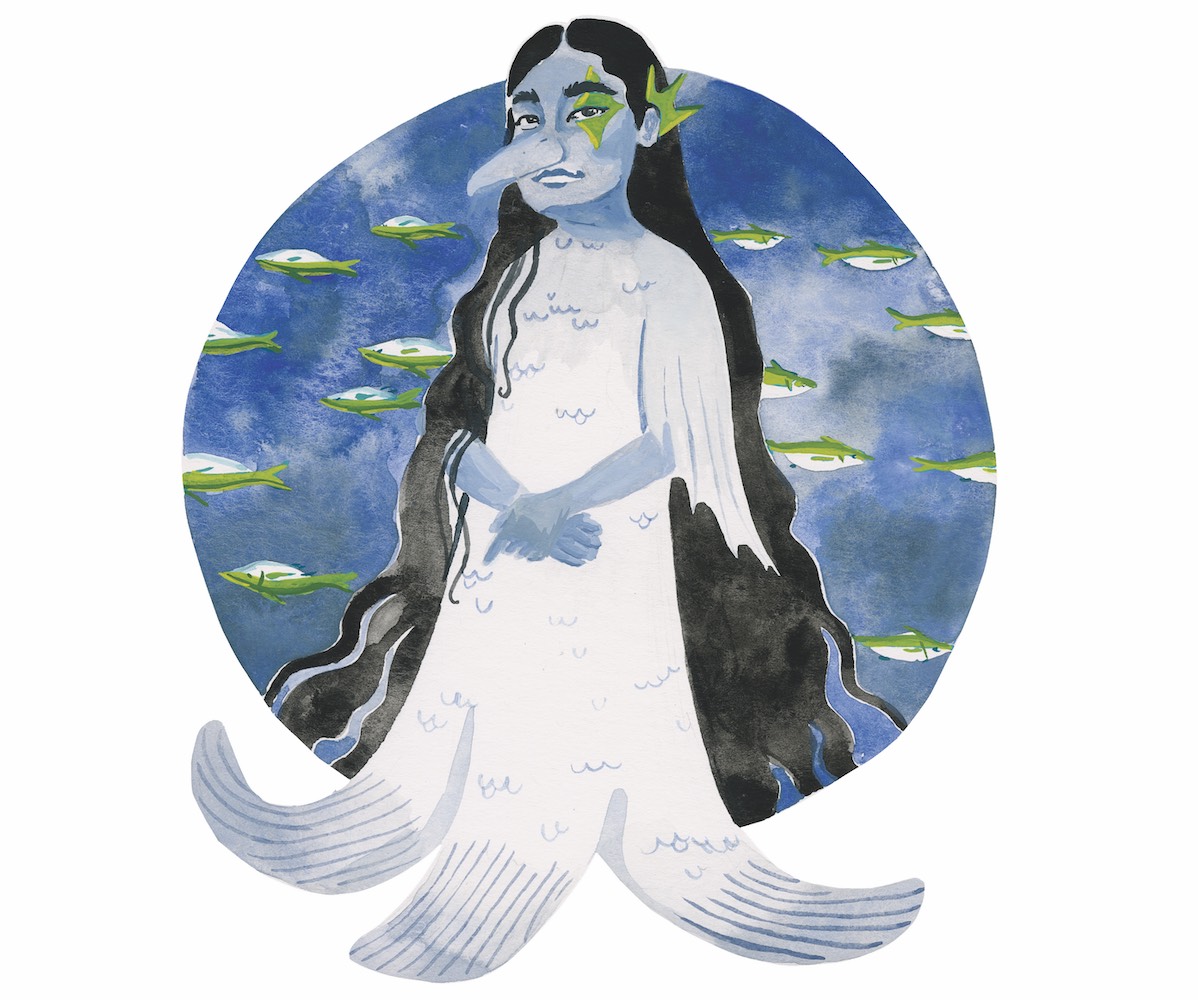

With illustration by her sister Cori, Lin weaves her own tale of coming of age, navigating love, a miscarriage, motherhood, and grief with those of yokai—or supernatural entities—from the Japanese, Taiwanese and Okinawan folklore of her heritage to shine a light on the monstrous and mysterious forces among us. Through the rokurokubi, a yokai whose head is able to detach from their body, she explores her teenage affinity for dissociation; through the baku, a nightmare-swallowing chimera, Lin writes about her father appearing in her dreams as she grieves his death.

I spoke with Lin over Zoom about how folklore and myth can help us better tell a truth, the volatility of truth and reality itself, and the state of mental health narratives today in a time of “therapy speak” and TikTok therapists.

Nicole Zhao: The use of folklore is interesting as a way to frame the stories of your life. What do you think folklore unlocks in understanding and telling the story of your life?

Jami Nakamura Lin: When I just try to write about myself, it just feels like tunneling towards the center of the earth and I can’t find my way back to air. Having context and seeing myself as part of a cultural lineage, having not just metaphors, but grounded examples of these legends and myths and monstrous figures really helps me see my stories in perspective, as part of a tradition, even though obviously they’re not exactly the same.

NZ: The first chapter in the book references “The Dragon King” and you cast your father in parallel to a mythical character. What inspired that chapter?

JNL: I was just thinking about this character, Urashimoto, who goes down under the sea, thinks it’s been three days, and comes back and centuries have passed. His world is completely changed and his parents are dead.

This idea of returning and everything changing was really resonant to me, especially since I’d gone to Japan for four months and when I came home, my father was dying. For me, the delineation in my life was not between when my father died and after, but between when I found out he was going to die and after. I thought, “Oh, this really feels like what I’m trying to express about my experience right now.”

My father’s death is one of my main reasons for writing this book. A couple years after someone dies, often people don’t know what to say about it or don’t wanna bring it up in case it’s upsetting. So writing the book is just a way for him to be amongst us and to keep us remembering him.

I could write this book again and in 10 years, it’d be completely different, because I’d have a different perspective on grief and motherhood and mental illness. It doesn’t necessarily negate the stuff that came before, but it’s just a different truth, a different type of excavation.

NZ: I feel like the book is as much about storytelling and the nature of truth as it is about your life and grief. I really enjoyed the chapter on how the story of Momotaro evolved over time to propagandize Japan’s nationalism and imperialism. There are also moments in the memoir where you write one thing and then a few pages later, you write that it actually wasn’t true. Why was it important for you to name the contradictions in stories and the ways that stories can evolve based on context and who’s telling it, especially in a memoir where the genre is based so much in fact?

JNL: I’ve always been interested in the difference between myth and history being who holds power at the time: who is naming something as history and who is naming something as myth. There’s this idea of the written historical record being the true thing. The things that are being told by communities, by families, by the people not in power are often given this legend aura. But truth is so subject to the context. I was trying to think about this project in a multiverse way. There’s so many different perspectives of what actually happened. There’s my sister’s story, my father’s, my mother’s—all of us could tell stories of our childhood and they all would be so different. We remember it slightly differently, because we’re different narrators. Our memory is fallible. But they are all equally important truths, and they all can happen at the same time, like Everything, Everywhere, All at Once, right?

People have always been writing speculative nonfiction work, it just hasn’t been labeled as this genre. Like Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior. It’s very interesting to me to think about the nature of truth, how things can be true and not true at the same time.

NZ: How would you define speculative memoir?

JNL: Jaquira Diaz had a really interesting talk about speculative nonfiction at Sewanee this year. She said that the speculative is involving the theoretical rather than the demonstrable, the figurative over the literal, ambiguity over knowing, and marked by questioning curiosity, but it’s all purposeful. It’s not making up for the sake of making it up, but rather to interrogate memory.

The word “speculative” is also fraught because so many religions, traditions, cultures have in their versions of reality things that would be considered speculative in Western culture.

Our monsters transform and we transform with them.

There’s always going to be those negotiations between whose version of speculation, whose version of reality is it. By writing speculative memoir, I am trying to put pressure on the idea of what reality is and whose reality it is.

Thinking about my episodes when I was younger, I was very uncertain about what reality actually was. I remember telling my psychiatrist, “I don’t know what’s actually happening.” My psychiatrist told me, ”Just don’t worry about that right now.” He was just trying to adjust my medication. And I wrote in my journal—I was 17—“How can I not be worried that I don’t know what’s actually going on?” Because it was all so confused in my mind at that time, hearing things that I wasn’t sure if I was actually hearing, stuff like that.

NZ: You write that your experience of being bipolar is feeling like you’re constantly doubting yourself. I was wondering if myth and legend felt like a way for you to legitimize your experiences of grief, or mental illness, or rage, even to yourself. Because people don’t question a myth or legend, in the way they might question mental illness.

JNL: It’s interesting you pulled out this idea of doubt ‘cause I didn’t even think about that. I do feel that, fundamentally, so much of my life is trying to figure out if my reaction to something lines up with reality.

What I love about the yokai is that people believe them. A yokai emerges out of the unknowable, the question of, “Why is this happening?”

Maybe trying to put my stories in the same parlance as folklore is trying to see them in this realm where reality or unreality is besides the point—belief is.

Grappling with Christianity also has a lot to do with that for me. Can I logically explain what I believe? No, I can’t. For me, it’s more emotive. I believe it’s true, but it also exists in this world of speculation to me.

I went to this fundamentalist high school for my sophomore and junior years. In our history class, we’d learn about Bible stories. So sometimes I wonder why I don’t know much about X, Y or Z historical event, and I was like, “Oh, because in my world history class, we spent six weeks talking about like Noah’s Ark. Right.”

This framework of faith undergirds a lot of how I think about other things, even though it might be unrelated. I have to accept for myself that I just won’t know.

NZ: You write in the book that most of the yokai you encountered through research rather than through your family and oral storytelling. You also write that you feel a nagging feeling that filling in the gaps with the research is somehow false or inauthentic. Similarly, I also don’t speak my ancestors’ native language, and I feel a lot of self-imposed shame and anxiety around reclaiming stories from Chinese mythology since I didn’t necessarily hear them passed down through my parents. How did you reckon with those feelings and get over that hump of thinking, “these mythologies or these stories are not mine to tell”?

JNL: This idea of authenticity can trap us. We have this idea that these stories that existed way back when in the old country are separated from us, now. One of the things I really wanted to do in this book is to ask, “How are these stories situated in Japanese America now?”

Cori, my sister who illustrated the book, also very much wanted to see these yokai, the way she illustrated them, as not happening in old Japan. They’re happening to Japanese America, to Taiwanese America, to Okinawan America, to us. That’s why the oni, the mallet-wielding ogre figure is drawn in front of the landscape of Amache, the incarceration camp that my grandparents were in.

Because of the normalization of mental illness and the invisibility of it, it’s easy for us to not think of ourselves as disabled or have solidarity with people who are disabled.

Japan is not this pure, authentic world that we are separate and distinct from, but rather this mutable, flawed and ever-changing culture that we descend from. People love this idea of cool Japanese cultural stuff from way back when, but then have no idea how much of Japanese America is so shaped by incarceration.

Research is important, like talking to people as much as you can. But a lot of people don’t have access to their families or communities because of forces of oppression. Whichever way people find out about stuff is a valid thing to do while also acknowledging our own positionality.

Researching yokai helped because yokai change so much. People are constantly inventing new yokai, they are constantly transforming. This idea of chosen transformation and change is important. Our monsters transform and we transform with them.

I’m trying to put aside the idea of authenticity and embrace the idea of transformation while also not pretending that I’m something that I’m not. So I resonate so much with what you’re saying about feeling that conflict. It is a complicated and difficult question. It’s different for different people and different situations. It’s something I’m still thinking about.

Why it’s so hard for a lot of us to write about these things and why white people write about us so easily is because they don’t have these fraught, emotional dynamics we all think about so deeply.

And then when white people write about our communities, it’s just like, “oh, I’ll do this research or not do this research and we’ll just write really easily” versus we’re like, “oh, but like my grandparents!”

NZ: With mental illness, there’s a lot more popularity around the topic now and especially with social media and TikTok, there’s “therapy speak” and vocabulary around trauma entering the mainstream. I’m curious about what you think of the public’s understanding of mental illness today and what’s still missing or off?

JNL: One thing that I’ve been thinking about more is how it fits into disability justice. For me, my mental illness is not visible because a) I have a lot of privileges and b) it’s managed right now. Unless I divulge to you, you would not necessarily know.

I’m not myself if I were not bipolar. I’m not myself without the loss of my father.

Because of the normalization of mental illness and the invisibility of it in some cases, it’s easy for us to not think of ourselves as disabled or have solidarity with people who are disabled. So I think some of that normalization does come at that cost of not working politically or in community with these other groups with whom we have a lot of overlapping interests; we are being oppressed by the same factors. And yet, because ableist society can accept us in certain ways, it’s easy to try to just want to slide into that.

And that’s only just speaking from myself and my own position in mental illness, because obviously for people who are more visibly mentally ill or mad with a capital M, that is not a choice that they get to make in the same way.

NZ: I appreciated that you were very explicit about the privilege of your family, your parents and finances. In some chapters, you acknowledge that what you’re going through is not as severe as what others have gone through, in regards to both your mental illness or your miscarriage. How did you reckon with that?

JNL: That’s something that I’ve always struggled with when reading other people’s books where they don’t talk about the money. Clearly, money is there. It was something that I did want to acknowledge because especially for mental illness, how much money you have makes the most difference. I feel like not talking about it is a disservice.

NZ: In the chapter where you’re under the Hello Kitty comforter and refusing to get out of bed, you address the readers as an audience and tell them that this is not the most important moment, but you know they need this in order to understand, otherwise the narrative is not going to be coherent. Why was it important for you to name that?

JNL: When I was growing up and reading these memoirs about mental illness, it was always based on this trajectory towards wellness, towards getting better, and then it’s over.

Whereas I feel like being bipolar and also ADHD, which I don’t talk about in the book since I wasn’t diagnosed until I was deep into the writing process, affects me in all these little ways in my day-to-day life.

The very extreme situations, like my hospitalizations, affect me much less than different dynamics with my family and stuff that we’re in family therapy for. It’s all these more minor, but daily situations that I feel make up so much more of the story than these crisis moments. And yet because of the salaciousness of those episodes, I feel like that is what gets a lot of the attention in the way that we talk about it in society.

It’s hard for other people to understand that kind of negotiation or to understand that perspective of difficult, but daily struggle versus crisis episodes. ‘Cause, a lot of people are really good in a crisis, right? Like Americans, we are good in a very short-term crisis. When it was like, COVID is going to be more than two weeks, then it’s like, “oh, we can’t deal with this anymore.”

NZ: I was trying to think about the link between your father’s death and your mental illness journey, and why you wove the narratives into one book. I feel like a big moment was during your major depressive episode, when your dad was like, “Do you need help?” And you were like, “Yes.” Also when he said, back when you were younger, “I don’t think she’s depressed,” and then admitting he was wrong later. Do you feel like that is why those things are so intertwined in your mind?

JNL: I think so. Also because my dad was a doctor, I deferred to my father so much in my life because he was the decision maker of our family. If dad thinks this, then this is right and I must be wrong. I knew he was wrong about me not being depressed, and I was very angry about that, but I didn’t know how to talk to him about it. So my dad shaped the trajectory of that in a way.

I have a lot of grief over my mental illness too. Not even my current iteration of my bipolar, but of what happened to me when I was in high school. I have a lot of grief over how difficult things were for me back then.

By writing speculative memoir, I am trying to put pressure on the idea of what reality is and whose reality it is.

I’m not myself if I were not bipolar. I’m not myself without the loss of my father. I don’t think of bipolar as a loss in the same way my father’s death is a loss. But all the effects of it when I was a teenager, that was a loss—having to lose a lot of friends or having to be hospitalized so many times or like having such hard fraught relationships with my family. Those things feel like losses because we didn’t know what was happening to me. It’s the loss of the life I could have had if I’d been treated properly when I first started exhibiting signs when I was 12.

NZ: I have a favorite yokai, but I have to ask, which yokai is your favorite and why?

JNL: Mine is the rokurokubi.

NZ: Oh my gosh, same! How did I know?

JNL: I’m getting her tattooed down the center of my arm this summer ‘cause her neck is so stretchy. My book is done, so I’m going to get a tattoo to commemorate her.

NZ: That’s an awesome tattoo.

JNL: I think about how some people think these stories started because they didn’t understand women’s illnesses or women’s mental illnesses. And just from the stories of rokurokubi themselves—this idea of being able to escape and separate from your body, always being hungry and looking for something, has always been very interesting to me, as someone who struggles with mind-body duality. She’s my fave.