As the next wave of non-geostationary satellite constellations seeks U.S. Federal Communications Commission permission to operate in V-band, antenna makers are racing to make business cases viable in this Extremely High Frequency (EHF) area of radio spectrum.

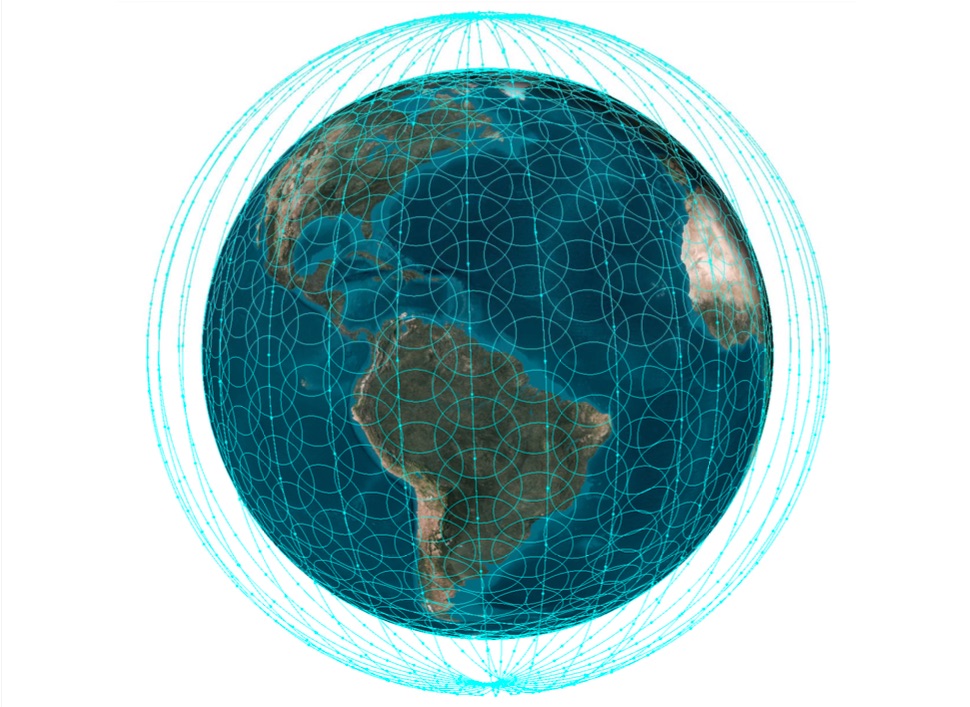

A variety of companies, some already operating spacecraft in other frequencies, filed for nearly 38,000 V-band satellites by the FCC’s Nov. 4 deadline.

The filings are the latest step for satellite operators marching to higher frequency bands that promise more bandwidth and throughput as they become harder to utilize, increasingly subject to weather attenuation and other issues.

Some analysts say the rush of V-band satellite hopefuls is merely a land grab for beachfront spectrum that could prove valuable later down the line.

Armand Musey, founder of advisory firm Summit Ridge Group, said “it’s doubtful that more than a fraction will get built.”

However, ground segment players are sniffing an opportunity they cannot afford to miss.

“This is an area that Kymeta is watching as our technology is well-suited to address the V-band,” said Ryan Stevenson, vice president and chief scientist at Kymeta, a metamaterials specialist developing terminals for NGSO operators in other spectrum bands.

Bill Milroy, chair and chief technology officer at antenna builder ThinKom Solutions, believes “a good number of these [V-band satellites] are going to go up,” in part because lower frequencies are becoming increasingly congested.

OneWeb and SpaceX’s Starlink, the two largest broadband megaconstellations, currently only use Ku-band to connect their rapidly expanding NGSO networks to users.

Milroy said: “It does beg the question, how will they not interfere with each other?”

He expects user terminals will be ready in “probably about the three-year time frame” for V-band, which is already used for gateways and other functions.

V-band terminals could come sooner from SpaceX if it continues its Starlink launch cadence.

SpaceX has launched more than 1,800 Starlink satellites in just two and a half years but only has Kuband licenses for 4,400 of them.

The company has a separate FCC authorization to launch 7,500 V-band satellites, which Starlink’s first generation needs to reach a total of 12,000 satellites for global services.

TECHNICAL HURDLES

Overcoming weather-related antenna challenges will be no easy task.

“The higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength, so even small objects — like raindrops — cause significant disruption,” said Andrew Bond, sales and marketing director at ETL Systems, which builds radio frequency distribution equipment.

Pandemic-related supply chain shortages are also weighing heavily on developmental progress.

“I don’t think anybody has escaped supply chain issues recently,” Bond said.

“However, the reality is that we’re rapidly running out of bandwidth in the currently available frequencies, and the pace at which we’re using it up is only accelerating. The industry is going to have to innovate, and do it quickly, to keep up with demand, logistics issues or not.”

Ultimately, however, regulatory obstacles could prove to be the biggest issue for these aspiring constellations.

Even with FCC approval, V-band NGSO operators will need landing rights for the countries they want to serve.

Because of the nature of their orbits, Milroy said these satellites would have to spend a lot of time over Russia, where they’ll need Russian government approval to operate, for instance.

It is unclear how willing Russia, China and other sizable nations will be to sanction these constellations while planning sovereign systems of their own.

These V-band constellations will also be competing with Starlink, OneWeb and other NGSO networks aiming to populate the skies in Ka and other bands.

Some of the V-band systems might end up combining with the current constellations, according to Musey.

“Managing the traffic to avoid collisions will become an increasingly complex task,” he added.

This article originally appeared in the December 2021 issue of SpaceNews magazine.