Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

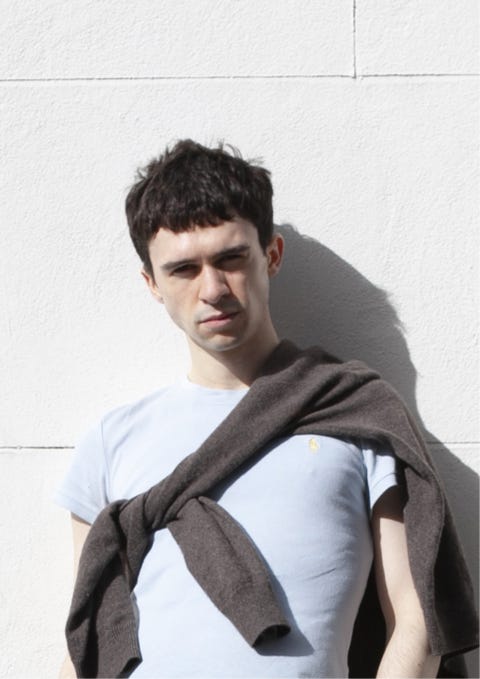

“You would almost think that it was intentional—I mean, it is intentional, at this point,” jokes Conner Ives of the American flag in the background of his Zoom square. The designer is dialing in from London, where he’s spent the day with his team going through “like 700 T-shirts” to eventually upcycle into his designs. But don’t let his location across the pond and his Central Saint Martins degree fool you. Ives is a native of the New York suburbs, and his fall 2021 collection, which also serves as his CSM graduation collection, is an examination of “the American dream.”

That is, he is quick to admit, “a loaded phrase, a minefield of sorts. And I did that intentionally. I think America’s whole history is kind of a minefield when you break it down. As much as we don’t really talk about it, there are very few moments in that long storied history that are great, glittering, positive examples of America.” He tapped into “a disillusionment with waste, a disillusionment with what we’ve kind of come to represent as a country,” but also a sense of optimism. The collection itself was “my means of getting back to an America that I loved.”

When he initially decamped for Central Saint Martins, Ives says, he had been eager to leave the States for some time. But distance bred fondness, as it often does. “It was never cool until I left. Growing up there, I just wanted to get out,” he says. Suddenly, when he was 3,500 miles away, “all I wanted was to come back home, do all the things I said I would never do.” And this season, he did come home in a sense, marinating in nostalgia from afar and feeding on references from his past. “I asked myself, ‘What did you love and who did you love and why did you love it?’ I realized that there were so many women, girls, friends, that I just fell in love with. How they put themselves out there, how they got dressed in the morning. What were they interested in? What were their references that then became my references?”

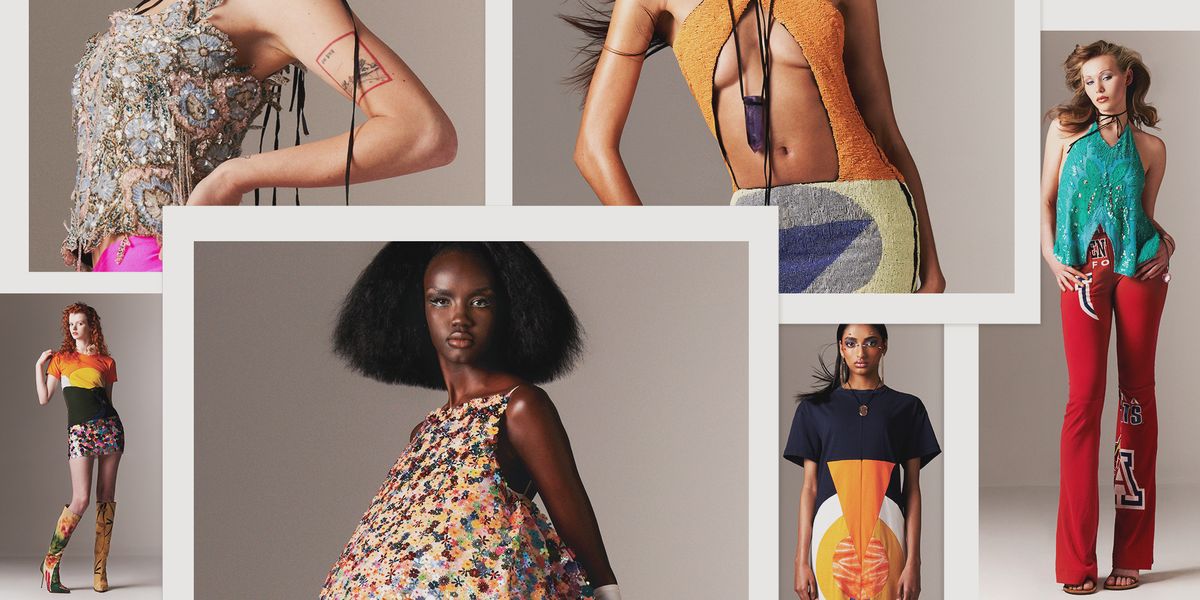

A whole cast of figures from his youth made their way into the collection. His mother collected American folk art, thus the use of those motifs in some of the looks. (“I think in this time that we are all desperate to see a little bit of a lighter, brighter, more optimistic America, and I loved what folk art did for that.”) His babysitter was so cool, he remembers, she was like a portal opening up a world of fashion and sophistication to him. And memories of his classmates, who loved yoga pants and “stringy little tops,” turned into archetypes that he channeled into the collection. Each look feels like it delineates a character drawn with Stanislavskian precision, from the modern debutante clad in a sparkly puffball of a gown to the party girl in sporty sweats and a going-out top.

Everything interests him, he tells me. “There is no point that I ever am like, ‘Oh, I’m bored. I’m going to stop looking at this.’ I could be anywhere and I would want to look at stuff.” And that fascination extends to the people around him. “I love weird. I think weird is the thing that makes the world spin. At a hypothetical party, I will always look for the weirdest girl, the loudest girl, or just the one that isn’t fitting in. And that’s who I make a beeline for. That’s who I want to have a conversation with because that to me is the future. That’s the girl that isn’t getting the attention, and I want to know what she’s wearing, what she’s thinking about, what she’s interested in and that then becomes what I’m interested in.”

As specific as it was to his own history, the collection ended up oddly resonating with fashion’s current themes as it strives for a coherent post-pandemic aesthetic. While we were all in quarantine revisiting teenage playlists, reading Jessica Simpson’s memoir and watching Framing Britney Spears, a Y2K revival that had already been simmering came to its boiling point on the runway. We saw everything from Bimbo Summit climbers at Blumarine to Kim Shui’s shiny, ruched, sweet nothings. “Everything is nostalgia now,” Ives says. But what’s different about this new era is “the shedding of the whole idea of what we can and can’t do. Or even the shedding of trends,” which he sees as being less and less relevant now that women themselves decide what to wear without waiting for outside direction.

At multiple points in our conversation, Ives uses the phrase “slow burn” to describe moments in his career. That might seem odd coming from a 25-year-old who worked for Rihanna before he even graduated college. But as he describes it, his creative process has been a series of gradually unfolding revelations. One was about the ecological footprint of his chosen industry. When he started interning at fashion brands, he found that entire rolls of fabric would go unused, and often he’d hear “ ‘Oh, give it to Conner. Conner will do something with it,’ ” he recalls. “I was shocked because I couldn’t believe that a roll of fabric that costs a big house like that thousands and thousands of dollars, they would just want to discard. There was a disillusionment there that made me feel really sick,” but also an opportunity–to create a brand that didn’t operate by the old, flawed standards. He didn’t want to “go and fall into bed at the end of the day and get a chill down my spine and be like, ‘This is so gross.’” Which means that, these days, he often finds himself contentedly “picking,” or going through bulk bins of discarded garments, to find the perfect canvases for his upcycled vision.

Then there was the Rihanna moment, which came about when he dressed Adwoa Aboah for the Met Gala while he was still in his first year at Central Saint Martins. The look caught Rihanna’s eye and pretty soon, he had a DM request to do a custom piece for her, which eventually blossomed into a job at Fenty. “What was so amazing,” about having her as a boss, he says, “was the democracy that she created in the structure of that company. It was never held against me, at least in her eyes, that I was too young.”

So while, like most successes, Ives’s didn’t happen overnight, being named a finalist for the LVMH Prize is a star-minting moment for him. And his hybrid of American sportswear comfort and eveningwear flash feels particularly of the moment. “We’re all desperate to put on something that’s tight and sparkly,” he says. “I know that I am. I know that a lot of my friends are, but then I also have a lot of friends that are like, ‘No, I love what we’ve been doing for the last year. I love that we’ve been in sweatpants from the waist down and maybe something a little bit more special from the waist up.’”

With his finalist status, you might just say his own American dream is coming true. “I’m in a complete state of disbelief,” he says, “but with that said, $350,000 would be fabulous.”

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io