Universal Magnetic: New Works by Terence Hammonds is currently showing at the Taft Museum of Art in Cincinnati, Ohio. Hammonds’s works in Universal Magnetic feature collages that combine historical images with decorative motifs that adorn and memorialize representations of racial identity in the United States. Curated by Ann Glasscock, the exhibition continues through June 4.

Michelle Johnson: Can you tell us about the name of this exhibition? Why Universal Magnetic?

Terence Hammonds: The title of this exhibition comes from a Mos Def (now known as Yasiin Bey) song. I chose the title because, to me, it speaks to you the way I think about history and as a repeating pattern. Also, for me, it speaks to the reverberations of love and dedication it takes to stand up for something you believe in for the greater good.

Johnson: One of your early projects joined social justice and hip-hop and included first-edition books from the Civil Rights movement. Could you tell us more about that project?

Hammonds: In the piece B-Boys breakdown, I printed the first reproduced images of break dancers on a set of Haviland, gold-rimmed, porcelain serving plates and platters. I also created a wallpaper pattern with portraits of the first 250 rap artists to record music. An attempt to make hip-hop, commemorative ware, or cultural heirlooms that are monuments to hip-hop.

The porcelain service ware was displayed in a cabinet I had broken off the front left. The cabinet was propped up on first-edition books that I collected in Boston. The books included a first edition printing of The White Negro, by Norman Mailer, a book of hymns and slave work songs from the 1800s, and a collection of poems, plays, and chapbooks from the Black Arts Movement in the ’60s and ’70s.

The point of it all is that histories are all interconnected. In my thinking, we wouldn’t have these cultural heirlooms if not for the work that has been done beforehand. I was trying to trace a line from hip-hop to the Black Arts Movement of the ’70s. I wanted to draw a correlation between the coolness of the Beat Generation and the hipness of bebop jazz with that of hip-hop culture and how the use of coded language can be traced back to the coded messages in slave work songs from the 1800s. The cultural institution of hip-hop doesn’t just come out of nowhere. It is, in fact, a part of a long tradition of African American art forms.

Johnson: Punk rock was an early inspiration for you. Is it still? How does it work its way into your art?

Punk permitted me to use my resources and hands to echo my voice.

Hammonds: Punk rock was a significant influence on me in my youth. I spent years as a teen in bands making flyers and zines. Punk dramatically influences the style of art that I make and my love of collage and screen printing. Punk permitted me to use my resources and hands to echo my voice.

I should clarify that I wasn’t a leather and spiked-hair kind of punk, but more of a K records, thrift-store cardigan, and zine-making kind of punk. I believe a big part of that ethos still influences the decisions I make today. My style of parenting. The type of instructor I am and the kind of citizen I am—one who questions authority and tries to leave the world a better place than how I found it.

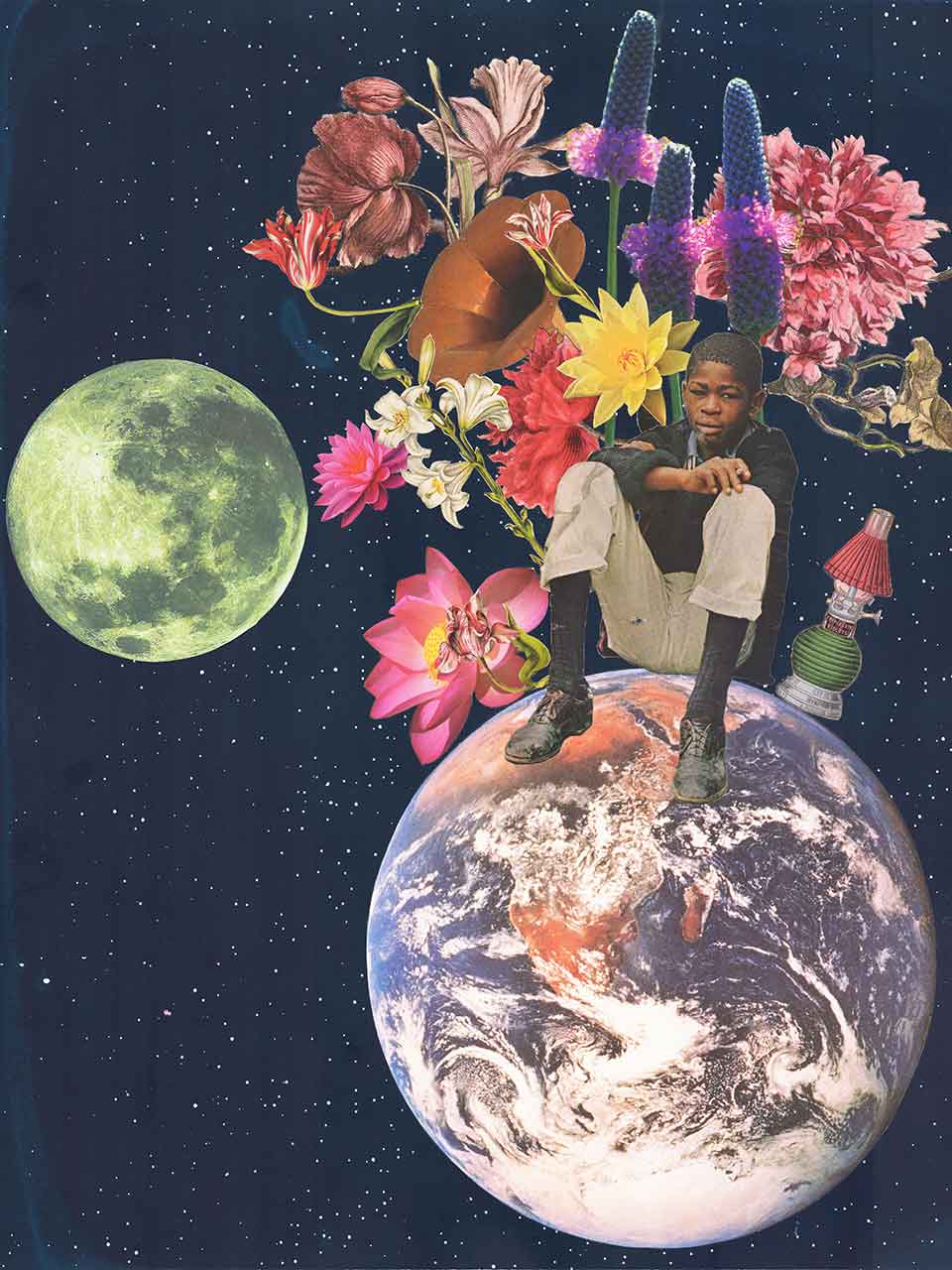

Johnson: In the paper collages in Universal Magnetic, you’re recontextualizing Black and Brown figures by removing them from scenes of pain and suffering and inserting them into spaces that celebrate joy and hope. What was your process when you created these collages?

Hammonds: Start simply by finding the image. I collect decommissioned library-bound volumes of vintage magazines. Some of these volumes are about six months of magazines and one bound edition. As I search the magazines, I look for images that resonate with me. Sometimes it’s just one figure out of a larger scene, and something feels right about liberating them from this historical context and placing them into my intergalactic fantasy world. It feels like a DJ sampling one breakbeat, repeating it, flipping it, and reversing it, looping it into something completely different.

It feels like a DJ sampling one breakbeat, repeating it, flipping it, and reversing it, looping it into something completely different.

Johnson: Your installations incorporate wallpaper. How did this evolve?

Hammonds: I believe it started when I was a student at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I was obsessed with the work of artists like Margaret Kilgallen and Barry McGee. It started with painting directly on the wall. However, that felt too derivative of my influences. I had already been screen printing for some time and wanted to set up a challenge for myself. Wallpaper provided the perfect vehicle for discussing race, class, and aspiration. I found a domestic setting the right place for sparking the type of discussions I hoped to have in the work.

Wallpaper provided the perfect vehicle for discussing race, class, and aspiration.

Johnson: Your work is often an homage to your heroes. Who are a few of your most dear heroes, and how have they appeared in your art?

Hammonds: The most obvious and, of course, one I hold dearest would be my mother, Deborah Hammonds, who taught me to question authority, even when she was that authority. She instilled a love of history and culture that I am so grateful for.

Bayard Rustin, Shirley Chisholm, Marsha P. Johnson, Kathy Y. Wilson. Honestly, I could go on and on. I believe the thread that connects all these people is that they all stood up for what they believed in, intending to make the world a better place for themselves and everyone. It’s a quality I most admire in people. It’s the act of loving America so much that you put your life on the line to make it a better place.

Johnson: How will we see your heroes incorporated into the current exhibit at Taft?

Hammonds: Particularly in the ceramic pieces in this exhibition, I would say. I see protest as a radical act of love. The act of organizing and risking your life for the betterment of society should be celebrated. I am attempting to create monuments to these radical acts of love. The images of protest are incorporated into the decorative motifs of the ceramic vases.

I see protest as a radical act of love.

Johnson: What was your artistic response to the early days of the pandemic?

Hammonds: I was lucky to have an exhibition booked with Cincinnati Art Museum’s recreational center. Although I must say at the time, I didn’t feel so fortunate, and for me, it was incredibly challenging to think about beauty or the importance of anything that I could do with my hands. Especially when being inundated with images of Black pain and suffering at the hands of police officers. Not to mention the worry and dread I felt as a parent of two young children with the uncertainty and lack of information about Covid-19. So, honestly, in the early days of the pandemic, my artistic expression was mostly limited to coloring with my kids and making lots and lots of cookies and pizzas.

I found it incredibly hard to try to be creative. So I relied on the thing that worked for me in the past, which was to get physical. I had a large wooden crate taking up precious real estate in my garage. I also had a considerable cache of stencils and screens from previous projects. I decided to break out the power tools and cannibalize that sizeable wooden crate. I cut some of the crate walls into squares, then painted various bright, cheery colors. Then used those old screens and printed those images on the squares. Later, between Zoom meetings and hanging out with my family, I would spend long nights with a scroll saw in the garage cutting out those printed wood images. Later I would collage and layer the images and then cover them with a polyvinyl resin. Those works became the installation Everything Is Everything at the Cincinnati Art Museum’s Rosenthal Education Center.

Johnson: Where else can we see your work? I noticed you have something new coming to the Newark Museum of Art.

Hammonds: My piece Black Abolitionist Wallpaper just opened at the reimagining of the Newark museum’s Seeing America exhibition. The curators did a great job pairing my wallpaper with Hiram Powers’s sculpture of The Greek Slave. It is part of a massive reimagining and reinstallation of their eighteenth- and nineteenth-century galleries. My intention with this piece was to put faces and names to the people who were doing the dangerous work of abolition in the 1800s. I wanted to add context and nuance to the understanding and interpretation of the sculpture.

Johnson: You live in Cincinnati. What are some of your favorite spots? Where do you find inspiration, joy?

Hammonds: I am endlessly inspired by the historical architecture in Cincinnati. I had the privilege of living in the historical district of Dayton Street. I lived in a carriage house of a home that was built in 1846. The main house, fortunately, survived many years with minimal renovations. So most of its decorative arts are still intact, from the fantastic bathroom tiles to the hand-painted ceilings and the micro mosaic tiles in the dining room. I am also, of course, inspired by the amazing cultural institutions like the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati. And the Taft Museum of Art. Cincinnati is also home to some amazing nature preserves, like the one at Lindner Park, where I spend a lot of time. My family and I love long walks at French Park as well. And for real joy, there’s nothing like a scoop of black-cherry-chocolate-chip ice cream from Graeter’s.