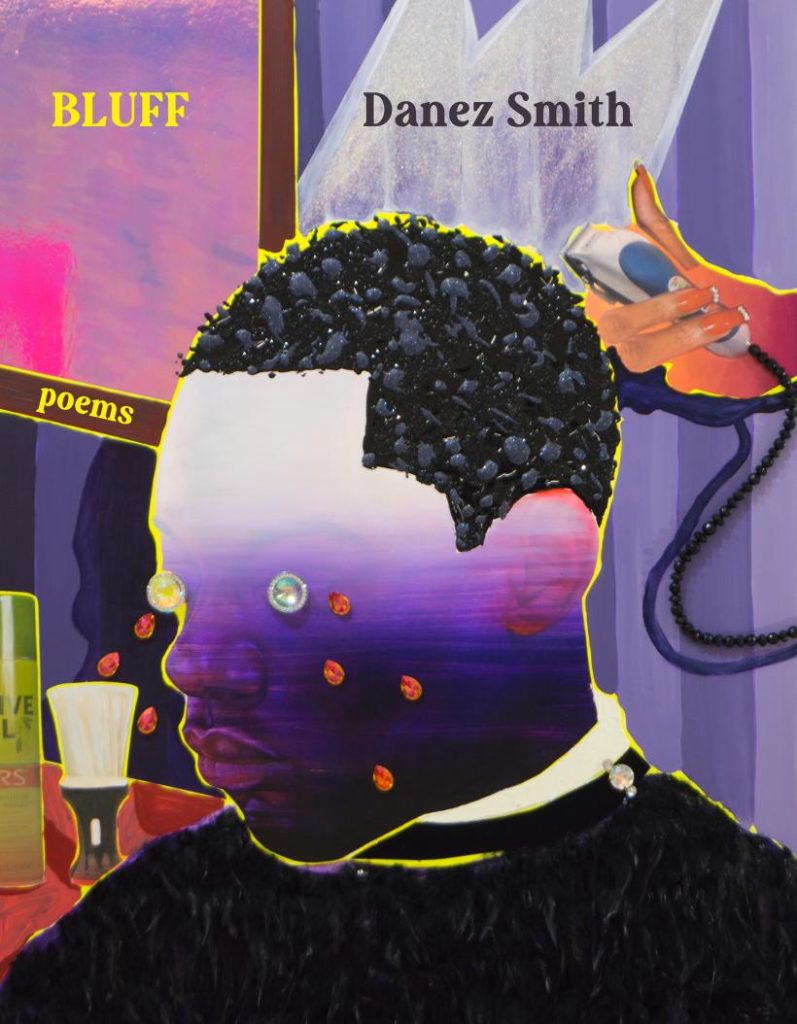

If Don’t Call Us Dead and Homie weren’t enough proof, Danez Smith’s Bluff confirms their importance in the poetic firmament through a magnificent array of form and content.

Smith’s singular voice dazzles, with subject matter that is both immediate and timeless. The poems are often a linguistic simitar about the world’s many injustices—whether it’s the systemic murder of Black people historically and today, or the devastations of climate change—and are equally wholehearted about love, and hope.

I had the pleasure of a generous and wide-ranging epistolary interview with Smith as they prepared for the publication of Bluff.

Mandana Chaffa: Prior to the epigraphs are the poems “anti-poetica” and “ars america (in the hold)” setting both the canvas and the stakes of what follows. In the former poem, despite the enumeration of what poetry can’t tangibly do—fix injustice, matter more than kindness, deliver freedom—what follows in the next 135 pages, proves why poetry is so valuable, even as the second poem is a kind of rooting, providing origin and geography. At what point in the process of creating this collection did these two poems arise, and did you always intend for them to be the preface?

Danez Smith: Leave it to a poet to start a long-ass book with a poem harping on the limitations of the form, right? I don’t remember exactly when I wrote those poems. I know “anti-poetica” came around when I was writing a bunch of ars poetica that were truly negative, maybe in a positive way, in their engagement with poetry. Near the revelation that these poems might be a book, my friend Angel Nafis gave it a read and gave me a good heart to heart about the inward critique and pessimism, the great weight of guilt in that early draft. When Angel says something, you listen. So I looked at what was the negative force in the poems and leaned into that negativity so I could clock it, control it, play with it, balance it out, and not submit to it all the same. I have a note in my phone that says “turn all the ars poeticas to anti-poeticas” and I think that accurate adjustment allowed me to seek poetry’s use solely in its failures. So, it made space for hope, for light, for a way forward.

I leaned into negativity so I could clock it, control it, play with it, balance it out, and not submit to it.

“ars america” was an older poem that had a different title, maybe it was even untitled, that gained its title once I knew what I was writing into: language, genre, art, land, history, truth. I wanted to think about the art of America with the poems under that title. How and what does America make? What is an ars america? It could only be violence. I didn’t intend for them both to be the preface while writing them, but they felt like they set a certain set of conditions and understandings from jump. I put “anti-poetica” up top, and I think it was my editor Jeff Shotts who suggested putting the other poem up top, too. I think they make a nice two-step before the rest of the book unfolds.

MC: Speaking of epigraphs, the selections by Amiri Baraka, June Jordan and Franny Choi, refer in part to a new life coming from destruction, which feels especially appropriate in our world on fire. Yet the mythology of the phoenix is complex: though the phoenix rises from the ashes of its immolation, it will never be the same being that it once was. Each of your collections has a distinct, wonderful Danez-ness to them, yet there’s also a kind of regeneration that consistently makes it new; is this kind of motion and conversation something you contemplate or is it only present after the fact?

DS: I don’t think it’s intentional. I think I’m just writing each poem or collection as they come, but after a collection is wrapped and in the world, it is fun to think on which poems feel like they have instructions to keep writing, dreaming, and asking into the work. From Homie I think the poems that most influenced Bluff are “waiting on you to die so I can be myself” and “my poems.” Those poems I can see myself already beginning to struggle with the themes and exfoliating self-investigation that Bluff handles, and I think “waiting on you to die…” opened up a door into new lyric possibilities for me. I’m grateful there might be some kind of signature that I’m subconsciously imbuing the poems with, but my only task and mission is to write new poems and hopefully not just re-writing old ones, though that does happen too and I am in love with the fact that sometimes the soul just needs to say something again and again until it is satisfied or transformed.

MC: Though all the poems are visual in varying ways, the progression of forms in your collections, and especially in Bluff, are purposefully acrobatic and often upend the experience of reading in a meaningful way. In a few places, the placement of text necessitated either turning the book, or my head (I chose the latter), and that shifting—one’s body, one’s eyes—was invigorating, as well as a QR code, cascading text, background color shifts. Or in the magnificent “rondo,” which offers a multitude of literary forms: an homage, an elegy, weaving history, and a kind of urban street plan of poetic phrases. Let alone the shattering footnotes, delegated to the bottom of the page, echoing the line in “anti poetica:” that “poems only live south of something / meaning beneath & darkened & hot”

How did you determine the architecture for these poems? Did any of the pieces begin in one structure, and move to a different poetic neighborhood?

DS: It’s all play, trial and error, what ifs, and a little bit of useful boredom, too. All of these poems start with the word first… is that true? Well, no. There are poems like “end of guns” that were just a regular-degular poem in stanzas before the collage came into its body, but there are poems like “rondo” where I knew for a long time what I wanted the shape to be, but I had to wait for years for the language to come. I love the visual fields that poetry holds so well, but nothing can start without the word for me. However, language sometimes does not satisfy, and when that’s the case I can ask “Is this just not the write words or is there something about the shape that I can manipulate to better get to the poem’s intended heart?” I try not to play for the sake of making a poem “different” for variety, but to really listen to the poem and ask how it wants to be embodied outside the confines of my mind.

MC: Your poems are some of my favorites to read aloud—sonic, exuberant, complex—and I was excited about the variety of oratorical possibilities, especially for the visually-forward pieces. They feel like the opposite of erasures, if that makes sense: the voices, the phrases, the unexpected frictions overflow onto the page, a chorus rather than a solo. What’s been your experience of reciting these poems?

Sometimes the soul just needs to say something again and again until it is satisfied or transformed.

DS: I love thinking about something as the opposite of erasure! Maybe that’s why this book ended up so goddamn long. I am excited to meet these poems in the air, but I haven’t had a lot of experience reading them aloud. I go to fewer open mics than I have in the past, I don’t slam anymore (for now), so I’m looking forward to reading these with audiences soon. I am, however, pulled toward what possibilities there are in video. There is a Keith Haring exhibition at a museum in town right now and one of the things I was most attracted to were his “tapes.” I think some of these poems might be better audiotized as tapes so that way the visual elements are not flattened by reading. I hope to get to play around with some ideas along those lines soon.

MC: English, unlike many languages, elects to center the “I” on a pedestal away from the collective; you, we, them, other pronouns aren’t capitalized. You nearly always employ a lower case “i” in your poetry and there’s intimacy and democracy in doing so (autocorrect keeps demanding I turn this into a capital “I”, as I assertively attempt to wrest control), an “us-ness” to it, that feels like the doorway to the kind of eden you’re depicting. How does your work navigate the distance—or intersection—between I-dentity and identity?

DS: Hmmmm…I am not sure! I think i-dentity, for me, stands in as a little plausible deniability in the lowercase i. There are aesthetic reasons I prefer the lowercase i and lowercase letters in general, but it also feels more playful, open, and moveable than the big I. You’re right on the money with that us-ness too. It feels, for me, like I have an easier time folding a “we” behind the little i. The ability to tie the personal to the communicable helps me decenter myself and keep the poetics open, breathing, influenced to the urgencies and pleasures of others around me. I do trust and know that there are moments to be self-absorbed, selfish, utterly and unapologetically internal, but I wanna also find bridges between that deep interiority and the ecosystems I am a part of. I-dentity then is necessary tool to seek out the self, before then turning towards i-dentity which lowers the guard rails and lets the world in. Something like that.

From “Last Black American Poem”:

“Forgive me, I wrote odes to presidents.”

MC: The interrelations of your poems—and collections—provides an unexpected reflection on what you’ve written in the past. I loved “my president” from Homie, but “Last Black American Poem,” and others in Bluff, offer a glimpse of something I rarely see elsewhere: your collections—and the past Danez and current Danez—interacting with each other, as well as how thoughtful you are about the passage of time, and all that it highlights or erodes. Or as you wrote in “on knowledge:” “i wanted freedom & they gave me / a name, it’s distracted me for long enough” // i had to move my mind outside my body / move my body like my mind / move my mind / deeper into the dark / question of its use”

Do you revisit your other poems, and do they inspire or determine what you write about currently?

Sometimes the idea of audience scares me; sometimes it hands me a righteous responsibility and purpose.

DS: I do! I love to sit down with my old work every now-and-then, be it book or draft, and see what I was up to, how I’ve changed, to see how I’m still the same or what I’m still chewing on. Sometimes there is a kindness and self-appreciation in that reading, sometimes an embarrassment and drive to correct something I thought or did comes about. Bluff wouldn’t have happened without those visits into my writing past, be it via the reflective self-critique vein of the book or because there are poems that were written alongside or in-between poems from my previous two collections. Hell, I almost put a poem from 2012, before my first collection, in the book with an addendum written in 2022. I feel inspired by my former selves. I love their stupid, messy asses. I am community with them, still learning their lessons and nursing their wounds. I am grateful to be able to witness myself from a different point in time and put new pieces to the puzzle.

MC: “My Beautiful End of the World” is a remarkable poetic essay about the disastrous state of the physical world, interspersed with beautiful imagery of Minneapolis where you are “returned into the delicious flaunt of nature” even as you reflect upon the planet’s barreling demise. I hope not to be one of your “hesitant cousins” or worse, but even though I have a MetroCard rather than a car, I too am complicit, as we all are. After I first read this poem, I turned 40 pages back to “Minneapolis, Saint Paul” which focuses on a more devastating destruction, the murder of George Floyd, that unimaginable nine and ½ minutes, and all that ensued. Can we talk about the long-form poems that spire through this collection like Redwoods and what they allow you to examine?

DS: We sure can! I love a long poem. The best poem I’ve written so far is the long poem “summer somewhere” that opens Don’t Call Us Dead (don’t tell my other poems I said that). For me there is a lot of excitement in the long poem, having to extend past the brief utterance into volta after volta, door after door journeying deeper into the poem and further away from what language or thought sparked the poems inception. No poems surprise me like what I find deep into those long poems. In the long poem, the unknown, the formerly unutterable must surface, the incantation of length summons it up if you are submitting to it right. I go to the long poem/the essay when I know what I want to say is only the surface, when the questions I have feel like they can’t just sit there and linger, like they must be embraced and dived into right then and there. Sometimes what happens is a much shorter piece is retrieved from that deep investigation, but in Bluff I chose for a great many to stay long. I had a lot to say and unfortunately for the version of myself that said before drafting this “I want a really short book this time,” I liked what I was writing and wanted to share as much as possible.

MC: I can’t stop thinking about a happy poem that exists joyfully before the entrance of the audience. Is it the same for happy poets? I realize there’s no singular answer, and it could change day by day, but what is the “heaven” of writing for you, and how much does the audience—beyond your circle of loved ones for whom, with whom, you create—weigh on you or the process.

I believe in the powers of declaration, manifestation, chant, song, repetition, devotion, and all the things that make prayer happen.

DS: Correct! There are Fiftyleven answers to that question. Here’s today’s: My writing heaven is being able to write honestly and imaginatively about my life, my world, my dreams, my hopes, angers, griefs, disappointments, and pleasures. It is a gift to be able to share that with anyone. Sometimes I keep things for myself. I’ve been journaling again for the last few years and having a private practice has made it easier to maintain a good relationship with my public one. Sometimes the “white gaze” is something I think about. Sometimes it’s too boring and unuseful to consider. Sometimes I want to write poems and get them quickly into the hands of beloved community members known and unknown. Sometimes the idea of audience scares me; sometimes it hands me a righteous responsibility and purpose. When I’m making a book, I must think about the audience, what the effect of writing these pulled together pieces is gonna have on someone and because of that I always try to imagine how reading one of my books might be of use to someone else’s living and working.

MC: I’m interested both in your perspective of the power of words, of repetitions, as well as what I’d call your innate hopefulness, which I feel threaded through the collection, regardless or perhaps because of the undiluted truths also embedded within.

DS: Beginning with hope, I think there are few greater gifts to offer someone. Grief, witness, shelter, solidarity, resources, so many great gifts, but hope offers us possibility, proposes transformation, and believes in the future. There’s a lot of feelings in my work, but I think if you look at the architecture of all my collections you’ll find that I am always trying to orient us towards hope, towards a great “someday” where we are all loved.

I love an “i want” in a poem. I think of my poem “Dinosaurs in the Hood” which is also made of those “wants.” You know, Mandana, maybe it comes back to prayer. I believe in its power. I believe in the powers of declaration, manifestation, chant, song, repetition, devotion, and all the things that make prayer happen. Maybe I believe the purest poem is a prayer, and all prayers are poem, and they have real, big, spiritually tangible consequences and…hopes! I think words have more powers than I can list or even think of, but I think part of the reason I was put on this earth and tasked to make use of language is to provide hope in the midst of darkness, to be one of a great many torches as we light our way through.

Read the original article here